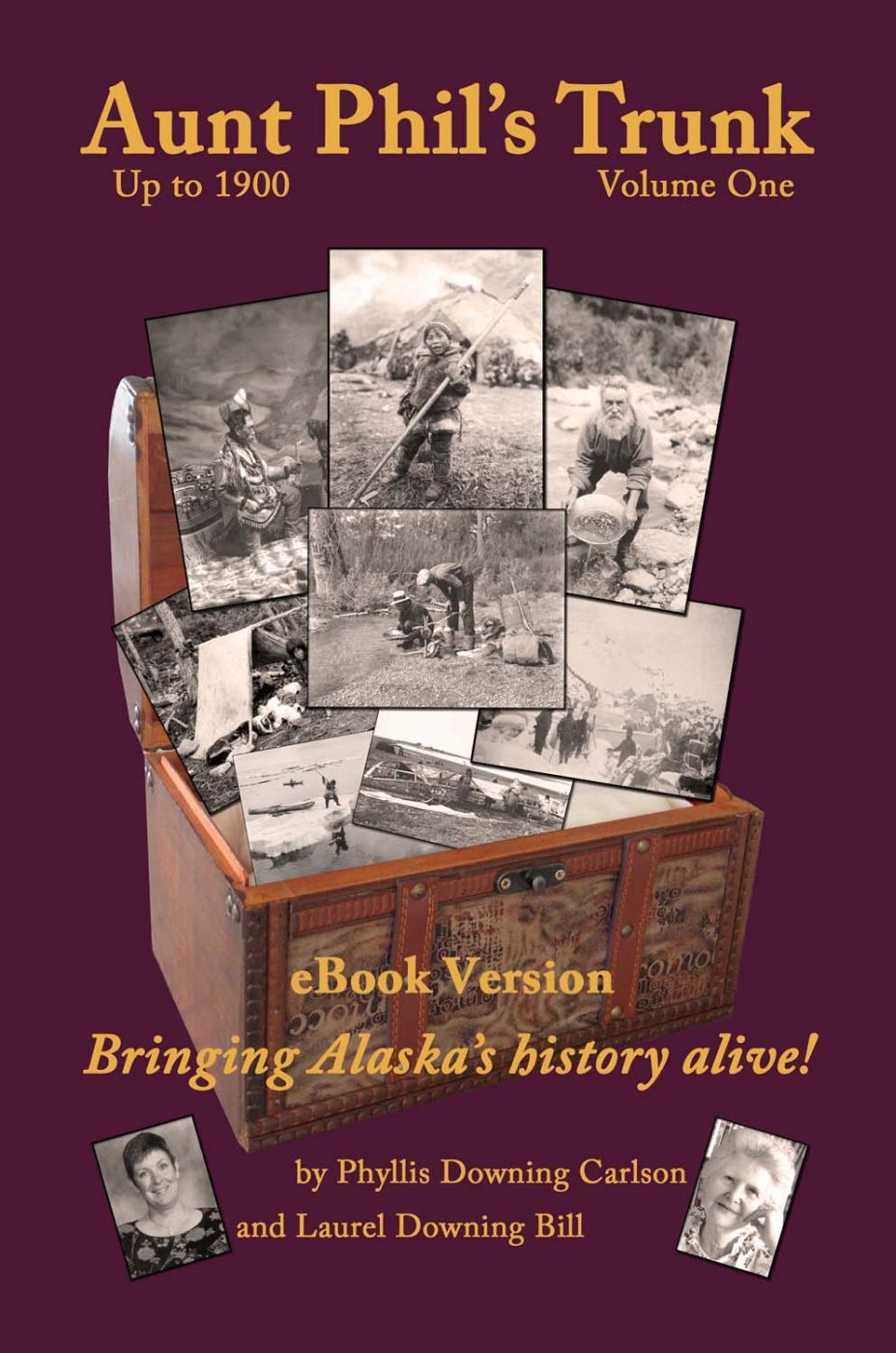

Aunt Phils Trunk

Volume One

Bringing Alaskas history alive!

By

Phyllis Downing Carlson

Laurel Downing Bill

Aunt Phils Trunk

LLC Anchorage, Alaska

www.auntphilstrunk.com

DEDICATION

I dedicate this first revision of Volume One to the memory of my paternal aunt, Phyllis Downing Carlson. She was one of Alaskas most respected historians, and without her lifelong interest, and then researching and writing about Alaska, this series would never exist.

I also want to dedicate the work to Aunt Phils stepchildren, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and their families; to my brothers and sisters, their families and all our cousins. And I dedicate the work to my husband, Donald; son Ryan and his wife, Kaboo; daughter Kim and her husband, Bruce Sherry; and Amie, Toby and Toben Barnes. Thank you so much for believing in me.

Lastly, I dedicate this collection of historical stories to my first grandchild, Sophia Isobel Sherry, as her giggles and slobbery baby kisses kept me sustained through long hours while beginning the Aunt Phils Trunk series back in 2005. Then to my second grandaughter, Maya Josephine Sherry, who arrived on the scene in 2006 and is a wonderful light in my life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe an infinite debt of gratitude to the University of Alaska Anchorage, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, the Alaska State Library in Juneau, the Z.J. Loussac Public Library in Anchorage, the Seward Community Library and the University of Washington in Seattle for helping me collect the photographs for this book. Without the patient and capable staffs at these institutions, the following pages may not have been filled.

I also want to extend a heart-felt thank you to Robert DeBerry of Anchorage for his excellent attention to detail as he readied for publication the majority of the historical photographs that appear in this volume of Aunt Phils Trunk. Thank you, too, to Ken Werning of Harlingen, Texas, for restoring a number of Aunt Phils old photos. And I am extremely grateful to Nancy Pounds of Anchorage for slaving away with her eagle eyes to carefully proofread the pages.

My family deserves medals, as well, for putting up with me as I chased down just the right photographs to go with Aunt Phils stories, poured over notes and the collection of rare books that make up Aunt Phils library and sat hunched over my computer for hours blending selections of Aunt Phils work with stories from my own research.

Aunt Phils Trunk, Volume One, shares stories of Alaskas first people, Russian fur traders and those rugged adventurers who traveled north when the Great Land became part of the United States. The tales and photographs in this book take readers up to the Klondike Gold Rush at the turn of the 20th century.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EARLY ALASKA

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

A fter teaching in remote Alaska communities and raising a widowers children, Phyllis Downing Carlson turned her attention to the history of the Great Land. Her quest for knowledge brought her a plethora of questions about Alaskas past, especially regarding the Cook Inlet area.

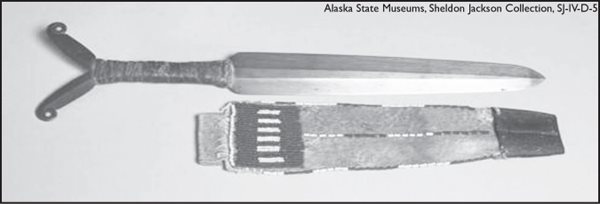

Archeological evidence suggests that much of Cook Inlet was occupied by Eskimos, who appear to have abandoned the area sometime during historical times. Copper knives, bracelets and beads, as well as metal-cut decorations, have been found around Kachemak Bay.

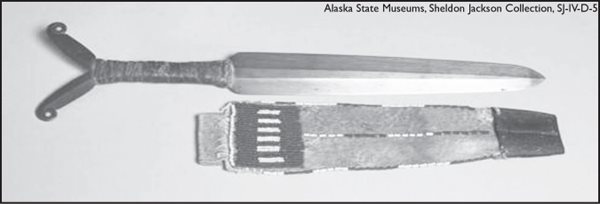

Copper knives, similar to the one shown here, have been found in Southcentral Alaska. This Athabascan knife was made by cold hammering, and then leather strips pad the metal handle. Moose hide made a good sheath.

Why was much of Cook Inlet abandoned by the Eskimos after more than 1,500 years of occupancy? Why and when did the Tanaina Indians (later known as the Denaina) move into this territory? Are the cave paintings found in remote sites in Cook Inlet and Kodiak connected with religious and magical practices and who painted them?

Phyllis found some questions answered during her 50-plus-year writing career and did not find answers to others. And sometimes she found that answers brought more questions as she interviewed archaeologists and scholars along the way.

Frederica de Laguna, a dedicated archaeologist who carried out a thorough study of the ancient Eskimo culture in Kachemak Bay during the 1930s, divided the Eskimo period into three stages, which she called Kachemak phases I, II and III. The first she placed at least as far back as 800 B.C., and perhaps farther. The last phase appears to continue to historical times and shows evidence of copper knives, bracelets and beads, as well as metal-cut decorations on artifacts.

William Workman, archaeologist and professor of cultural anthropology at the University of Alaska Anchorage, and his wife, Karen, excavated on Yukon Island and found more copper articles. William Workman wrote there may have been another late prehistoric Eskimo occupancy and, he said, there is still virtually everything to learn about the crucial period in Kachemak Bay pre-history.

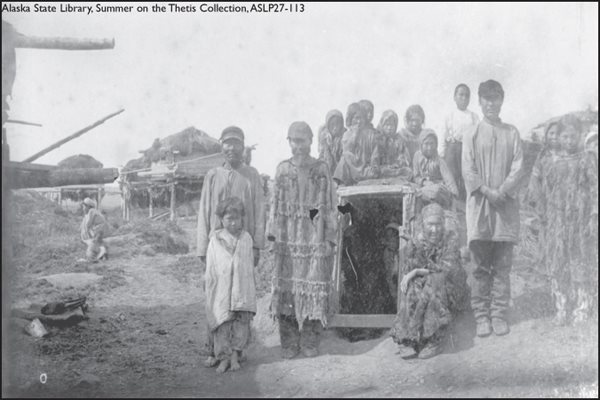

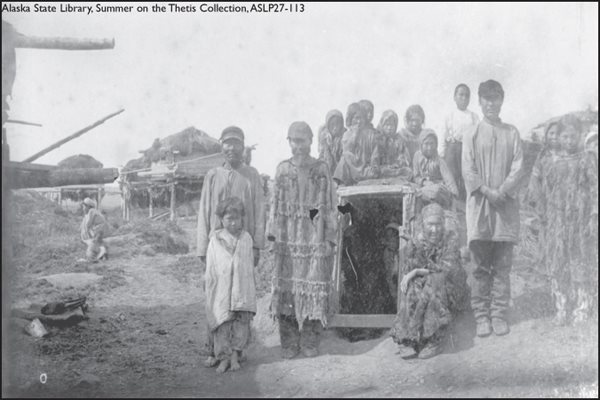

Some Alaska Eskimos lived in partially underground dwellings called barabaras.

And although English Bay and Port Graham still have settlements of Eskimo people, locally known as Aleuts, the answer to why most of the Eskimos left the lower Inlet still puzzles researchers. Were they driven out, did they die out, or, in the process of development, did their elements recede into the background, possibly under Indian influence, as Hans Georg Bandi suggested in his book, Eskimo Pre-History.

At any rate, Cook Inlet has been the scene of unsettled and disputed ownership, and during the last decade of the 18th century when the Russians entered the picture, there were midnight raids, ambushes and open warfare, according to historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, author of History of Alaska, 1730-1885. The Tanaina Indians of the Kenai Peninsula did not welcome the Russians by any means, and their hostility limited Russian expansion in this part of Alaska.

Why and when did the Tanaina people arrive on the Inlet? That has not been answered, either. The Athabascan nation, to which the Tanaina belong, stretches through Interior Alaska and Canada. They are connected with the Navajo and Apache by the Na-dene language. De Laguna quotes William Healy Dall, 1880 census-taker Ivan Petroff and Baron Wrangell as saying that the Tanaina are relative newcomers to Cook Inlet. Just when the migration took place only can be determined by more archaeological work in the upper Inlet.

One ethno-historical study by Joan Townsend places the beginning of Tanaina occupancy around 100 years before the coming of the Russians in the last quarter of the 18th century.

When Stepan Glotov, an early Russian fur trader, reached Kodiak in 1762 to trade with the Koniags, a boy told him that they often traded with the Tanainas of Cook Inlet the earliest reference to the Tanaina. This indicates they were already established before European contact. When Capt. James Cook, in 1778, described the people he met in what is today known as Cook Inlet, they and their culture strongly resembled some late descriptions of the Tanaina.