Aunt Phils Trunk

Volume Two

Bringing Alaskas history alive!

By

Phyllis Downing Carlson

Laurel Downing Bill

Aunt Phils Trunk LLC

Anchorage, Alaska

www.auntphilstrunk.com

DEDICATION

I dedicate this first revision of Aunt Phils Trunk Volume Two to the memory of my paternal aunt, Phyllis Downing Carlson. She was one of Alaskas most respected historians, and without her lifelong interest, and then researching and writing about Alaska, this series would never exist.

I also want to dedicate the work to Aunt Phils stepchildren, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and their families; to my brothers and sisters, their families and all our cousins. And I dedicate the work to my husband, Donald; son Ryan and his wife, Kaboo; daughter Kim and her husband, Bruce Sherry; and Amie, Toby and Toben Barnes. Thank you so much for believing in me.

Lastly, I dedicate this collection of historical stories to my granddaughters, Sophia Isobel and Maya Josephine Sherry, who remind me how important it is to preserve our past for their future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe an infinite debt of gratitude to the University of Alaska Anchorage, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, the Alaska State Library in Juneau, the Z.J. Loussac Public Library in Anchorage, the Seward Community Library and the University of Washington for helping me collect the photographs for this book. Without the patient and capable staffs at these institutions, the following pages may not have been filled.

I also want to extend a heart-felt thank you to Robert DeBerry of Anchorage for his excellent attention to detail as he readied for publication the majority of the historical photographs that appear in Volume Two of Aunt Phils Trunk. And I am extremely grateful to Nancy Pounds of Anchorage for slaving away with her eagle eyes to carefully proofread the pages.

My family deserves medals, as well, for putting up with me as I chased down just the right photographs to go with Aunt Phils stories, poured over notes and the collection of rare books that make up Aunt Phils library and sat hunched over my computer for hours blending selections of Aunt Phils work with stories from my own research.

Aunt Phils Trunk Volume Two shares the stories of various adventurers who traveled through Alaska and the Yukon Territory of Canada and settled in the Great Land. It continues from the Klondike Gold Rush at the turn of the 20th century and spotlights the settling of numerous communities, criminals and lawmen arriving in the Last Frontier, how rugged individuals struggled through the wilderness to set up a postal system and much more.

GLIMMERS OF GOLD

BORDER DISPUTE HEATS UP

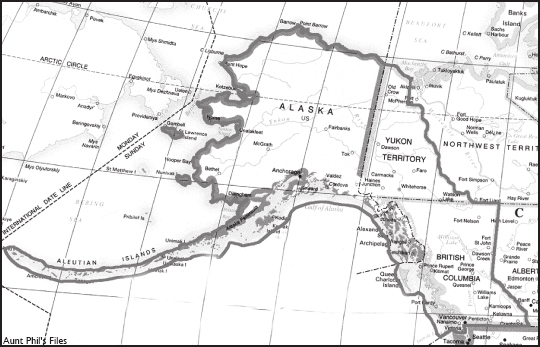

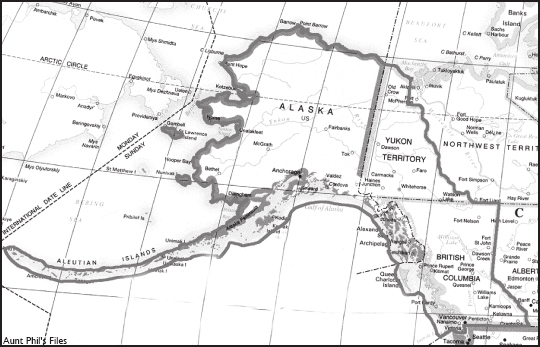

A laskas border with Canada is one of the great feats of wilderness surveying. Marked by metal cones and a clear-cut swath 20 feet wide, the boundary is 1,538 miles long.

The line is obvious in some places, such as the Yukon River valley, where crews cut a straight line through forest on the 141st Meridian. In other areas, like the summit of 18,008-foot Mount St. Elias, the boundary is invisible.

Starting in 1905, surveyors and other workers of the International Boundary Commission trekked into some of the wildest country in North America to etch a new boundary into the landscape.

But there was no border in 1867, when the U.S. purchased Alaska from Russia for 2 cents an acre. And the lack of an agreed-upon boundary caused problems from the get-go.

Maps of the time showed more land belonging to the Russians than was stipulated in an 1825 treaty between Russia and Great Britain. That treaty divided the Northwest American territories between the Hudsons Bay Company and the Russian-American Company trading areas and described the boundary as following a range of mountains in Southeast Alaska parallel to the Pacific Coast but in some places there were no mountains.

In 1872, British Columbia petitioned for an official survey to set the boundary, however the United States repeatedly refused, claiming it would cost too much.

The border separating Alaska and Canada stretches 1,538 miles from the tip of Southeast Alaska on the Pacific Ocean up to the Arctic Ocean and Beaufort Sea.

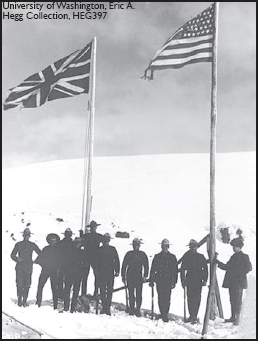

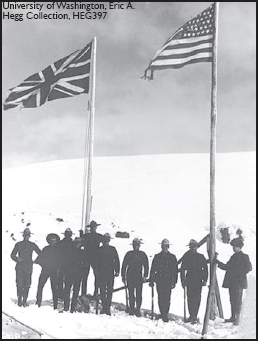

Mounties guard the Canada/Alaska border at the turn-of-the-last century.

Canada surveyed the boundary at the Stikine River in 1877, so it could set up a customs station to collect duty on goods headed to the Cassiar gold fields discovered in 1872. In 1887-1888, and again in 1895, William Ogilvie surveyed the area around the Fortymile gold discoveries.

But it was the Klondike Gold Rush that brought the boundary issue to a head. When every square foot of ground could yield enormous wealth, the exact location of the border became critical. In fact, the total value of the gold mined in the Yukon was nearly $2.5 million in 1897 and almost $22.3 million in 1900.

The Canadians sent a detachment of North-West Mounted Police to the head of the Lynn Canal, a main gateway to the Yukon, in the late 1890s. Canadian officials wanted ownership of Skagway and Dyea, which would allow Canadians access to the Klondike gold fields without crossing American soil. Canada asserted that that location was more than 10 marine leagues from the sea, which was part of the 1825 boundary definition.

But prospectors flooding into Skagway didnt agree. Some say that a group of heavily armed Americans demanded the Canadian flag at the police post be taken down or the Americans would shoot it down. Americans thought that the head of Lake Bennett, another 12 miles north, should be the boundary between the two territories.

The Canadians retreated and set up posts on the summits of the Chilkoot Pass and White Pass each post equipped with a mounted Gatling gun.

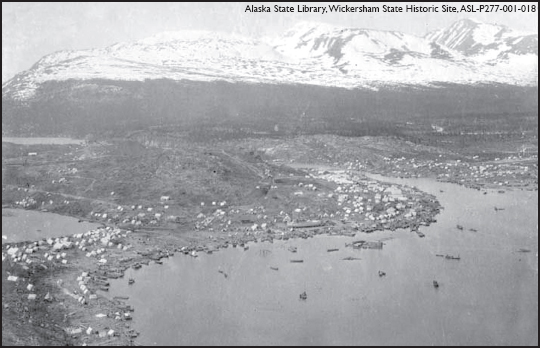

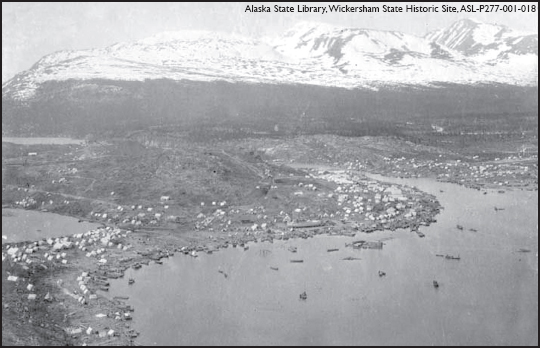

Stampeders heading toward the gold fields of the Klondike pitched tents along the shores of Lake Bennett, pictured above in 1898.

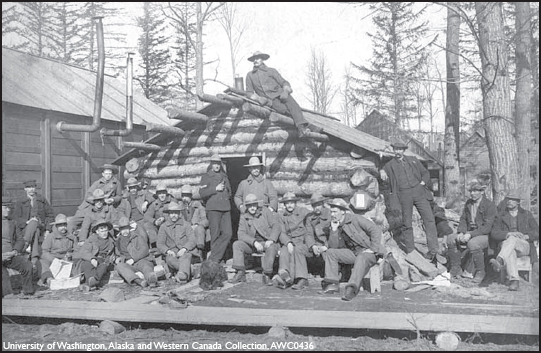

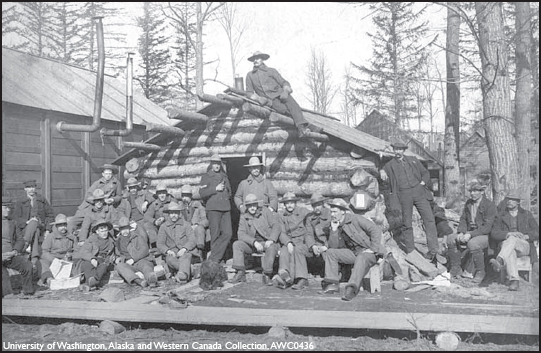

U.S. troops stationed at Dyea during the Klondike Gold Rush tried to keep peace and order among the stampeders.

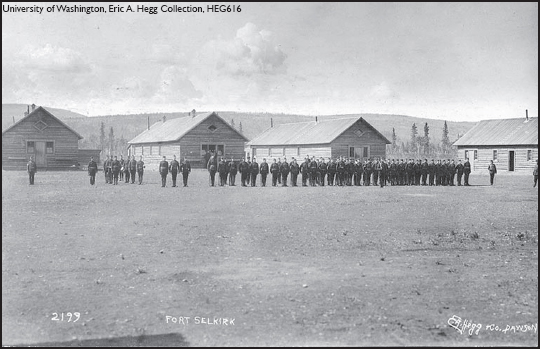

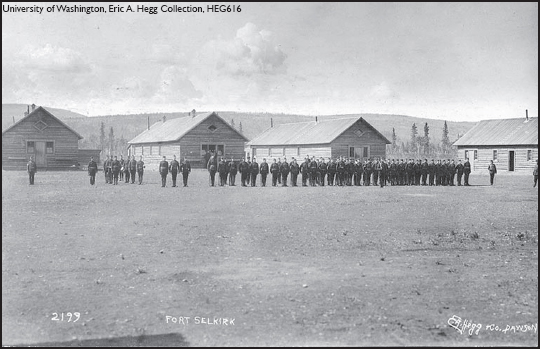

Troops perform drills at Fort Selkirk, which became the headquarters of the Canadian Armys Yukon Field Force in 1898.

The Yukon Field Force, a 200-man army unit, then set up camp at Fort Selkirk. From there, soldiers could be dispatched quickly to deal with disputes at either the coastal passes or the 141st Meridian.

The provisional boundary was grudgingly accepted, but in September 1898, serious negotiations began in Quebec City between Canada and the United States to settle the issue.

While officials were mulling over what to do about the border, other people were busy building the White Pass and Yukon Railroad through the disputed territory. And they had their share of problems, too.