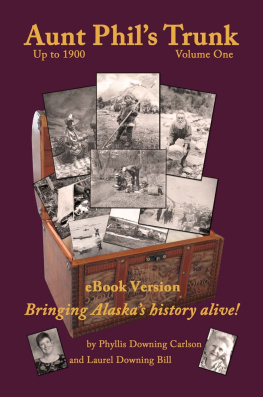

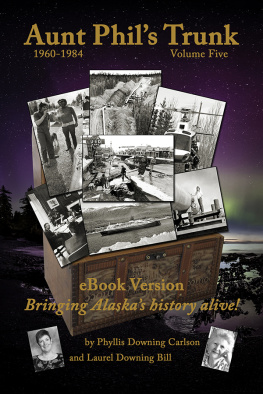

Aunt Phils Trunk

Volume 3

Bringing Alaskas history alive!

By

Phyllis Downing Carlson

Laurel Downing Bill

Aunt Phils Trunk LLC

Anchorage, Alaska

www.auntphilstrunk.com

DEDICATION

I dedicate this first revision of Aunt Phils Trunk Volume Three to the memory of my paternal aunt, Phyllis Downing Carlson. She was one of Alaskas most respected historians, and without her lifelong interest, and then researching and writing about Alaska, this series would never exist.

I also want to dedicate the work to Aunt Phils stepchildren, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and their families; to my brothers and sisters, their families and all our cousins. And I dedicate the work to my husband, Donald; son Ryan and his wife, Kaboo; daughter Kim and her husband, Bruce Sherry; and Amie, Toby and Toben Barnes. Thank you so much for believing in me.

Lastly, I dedicate this collection of historical stories to my granddaughters, Sophia Isobel and Maya Josephine Sherry, who remind me how important it is to preserve our past for their future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I owe an infinite debt of gratitude to the University of Alaska Anchorage, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, the Alaska State Library in Juneau, the Z.J. Loussac Public Library in Anchorage, the Seward Community Library and the University of Washington for helping me collect the photographs for this book. Without the patient and capable staffs at these institutions, the following pages may not have been filled.

I want to extend a heart-felt thank you to Robert DeBerry of Wasilla for his excellent attention to detail as he readied for publication the historical photographs that appear in Volume Three of Aunt Phils Trunk. I also am extremely grateful to Nancy Pounds of Anchorage for slaving away with her eagle eyes to carefully proofread the pages. And special thanks to Joe Koczan of Harlingen, Texas, for keeping me on track to finish the book when I sometimes just wanted to bask in the warm sunshine of Southern Texas.

My family deserves medals, as well, for putting up with me as I chased down just the right photographs to go with Aunt Phils stories, poured over notes and the collection of rare books that make up Aunt Phils library and sat hunched over my computer for hours blending selections of Aunt Phils work with stories from my own research.

Aunt Phils Trunk Volume Three is filled with stories about the birth of Anchorage and the Matanuska Valley, the early days of daredevil flyboys and other tales of courage and fortitude shown by Alaskas early pioneers.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EARLY COOK INLET

COOK INLET TIMELINE

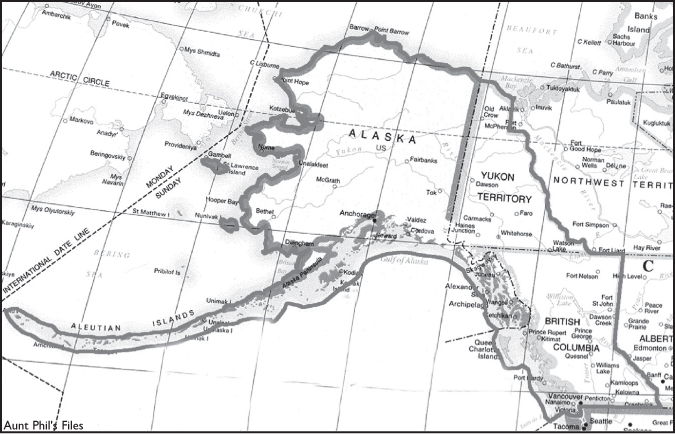

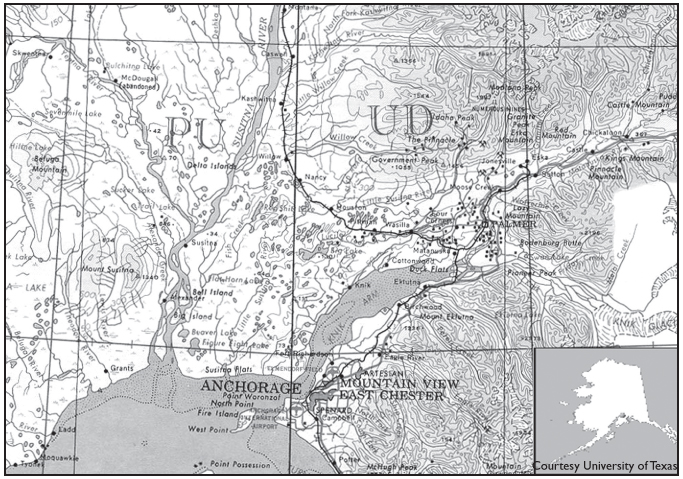

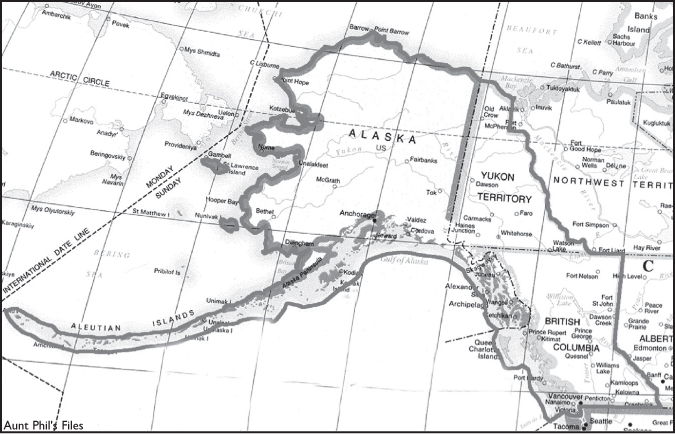

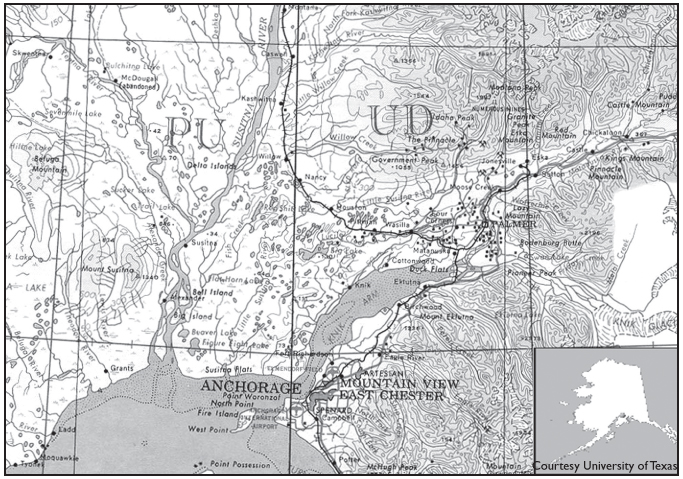

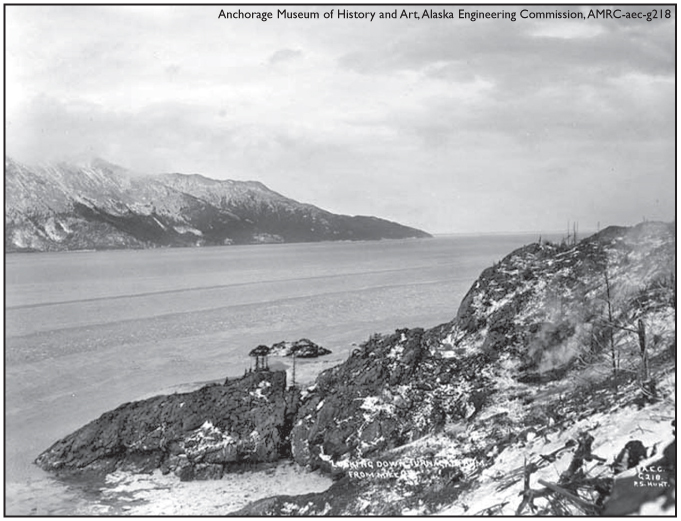

A s late as 1914, there was no town at the head of Cook Inlet. There was only a spot called Ship Creek, where small ships entered because the water was deep enough to transport cargo to trading posts scattered in the area.

Large ships anchored off Fire Island, lower center left, and freight then was transferred to smaller ships that carried cargo to settlements up Knik Arm.

Based on anthropological data from the Beluga Point area near Anchorage, the earliestknown human habitation of the Cook Inlet area was by Eskimo people about 3000 B.C.

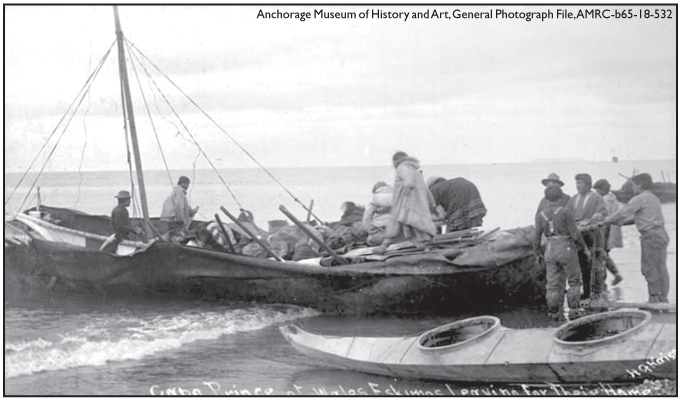

But long before white settlers plied the waters of Cook Inlet, Native Alaskans roamed the territory living a subsistence lifestyle in the bountiful country.

Early human habitation

According to anthropological research around Beluga Point in Southcentral Alaska, human occupation of Cook Inlet occurred in three waves: the first wave of Alutiiq Eskimos around 3000 B.C., the second in 2000 B.C. and the third at the start of the new millennium.

Athabaskan Denaina Indians entered Cook Inlet through mountain passes to the west as early as 500 A.D. and as late as 1650 A.D., displacing the Eskimos.

It is estimated that more than 5,000 Denaina inhabited the Southcentral area at first contact with Europeans in 1756.

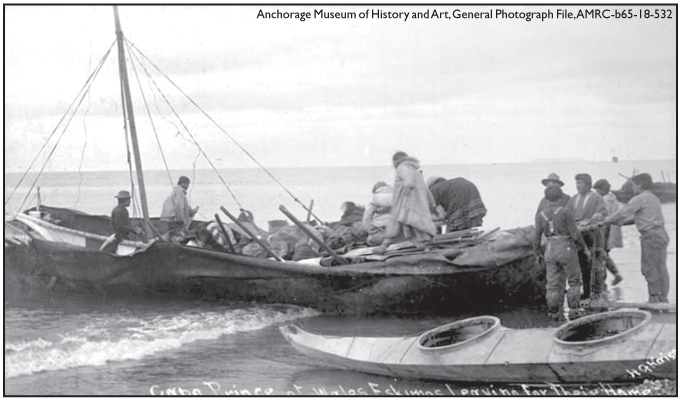

The Denaina, also called Tanaina, adapted the Alutiiq peoples knowledge of living in a coastal region, such as using kayaks for saltwater fishing, and subsisted entirely on the fisheries and wildlife.

They migrated with the seasons, fishing inlet streams and hunting goat and sheep along the upper reaches of Ship Creek in the summer.

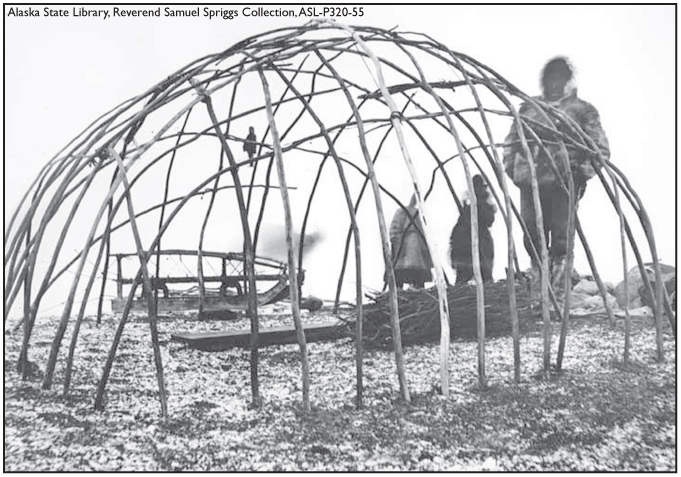

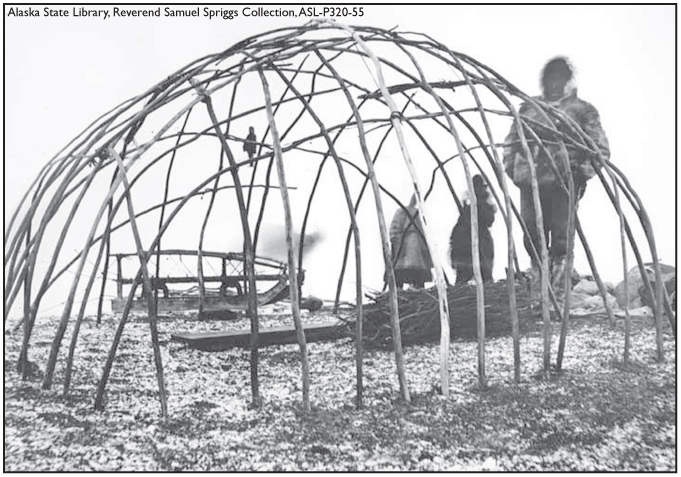

Natives made summer shelters from willows bent into shape and covered with skins.

In the fall, they hunted caribou in the foothills and moose and beaver in the basin. The Indians spent winters at trading route junctions, where they traded with the Ahtna Indians of the Copper River and Denaina who lived on the lower inlet at Point McKenzie.

1778: Capt. Cook enters Southcentral

Recent research indicates that it was Denaina Indians that met Capt. James Cook in May 1778 when he entered what is now known as Cook Inlet. Cook did not name the inlet instead he called it River Turnagain. British Lord Sandwich later ordered that it be called Cooks River. Explorer George Vancouver changed River to Inlet in 1792.

During his exploration of the coast, Cook noted that there is not the least doubt that a very beneficial fur trade might be carried on with the inhabitants of this vast coast. But unless a Northern passage should be found practicable, it seems rather too remote for Great Britain to receive any emolument from it.

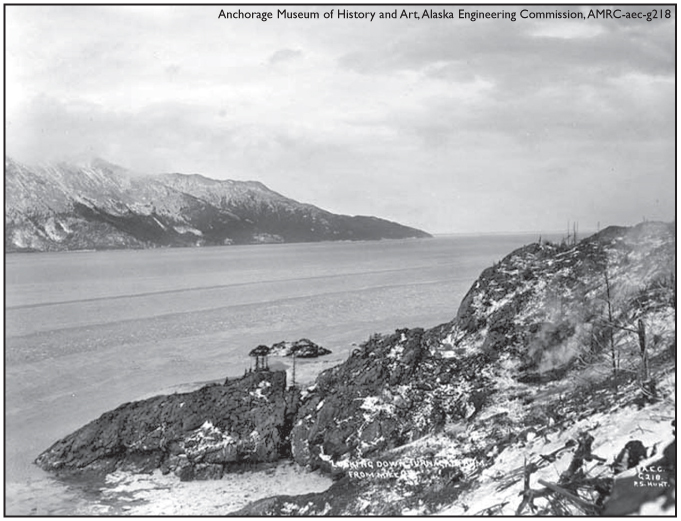

While on his third voyage of discovery in 1778, English explorer Capt. James Cook mistook one of the arms of Cook Inlet for a river and named it River Turnagain.

1786: Russians build trading posts

The Russian Shelekhov-Golikov Company established a trading post at English Bay near the mouth of Cook Inlet in 1786. Farther up the inlet, rival Lebedev-Lastochkin Company founded Fort St. George at Kasilof, and in 1791, built Nikolaevsk Redoubt at Kenai above Kasilof.

The only Russian trading post on the upper Cook Inlet was at Niteh, on the delta between the Knik and Matanuska rivers. And Russian Orthodox missionaries established a mission at Knik, on the western shore of Knik Arm, in 1835.

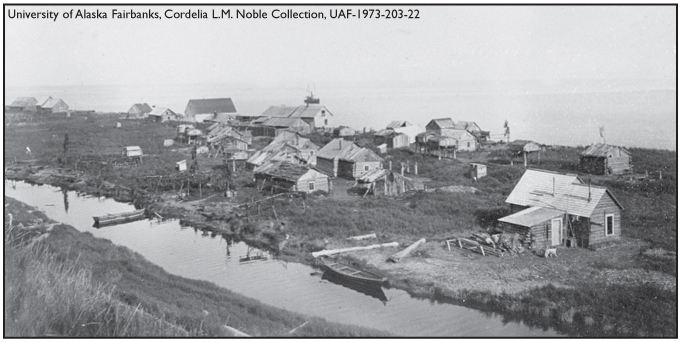

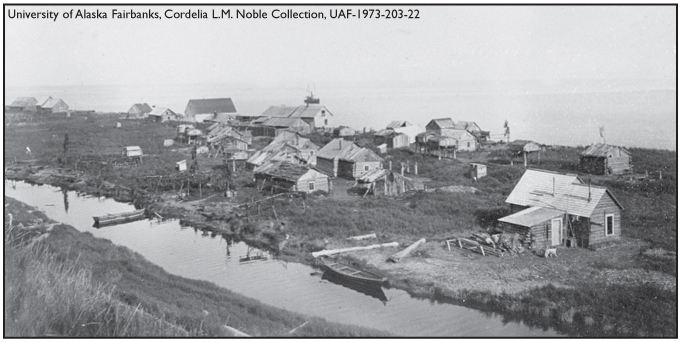

By 1845, the Denaina population in villages like Tyonek, pictured here around 1900, was decimated by smallpox.

1839: Russians bring disease

But along with their language and religion, the Russians brought smallpox and tuberculosis. The population of the Denaina in the upper inlet plummeted to 816 by 1845, half of what the Russians had counted when theyd arrived 10 years earlier.

By 1850, after Czar Paul I granted a monopoly to the Shelekhov-Golikov group, former Russian workers established small agricultural settlements along Cook Inlet at Seldovia, Ninilchik and Eklutna.