John Wilson Fosters new book is a gem in every sense: small but perfect in the hand, elegantly written and full of evocative, deeply researched interest, both in the bird and American social history. Michael Viney, Irish Times

Foster has produced one of the loveliest of literary meditations on the pigeon and its fate. Rick Wright, Birding

Among John Wilson Fosters books are Nature in Ireland: A Scientific and Cultural History (senior ed., Lilliput, 1997), Titanic (Penguin, 1999), The Age of Titanic: Cross-Currents in Anglo-American Culture (Merlin, 2002), The Cambridge Companion to the Irish Novel (ed., Cambridge University Press, 2006) and Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture (Irish Academic Press, 2009). He was born and educated in Belfast, received his PhD from the University of Oregon, and spent his teaching and research career at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. He is currently Professor of Modern Irish Literature at the University of Ulster. He has been an amateur ornithologist on both sides of the Atlantic for several decades and became intrigued by the extraordinary life and strange death of the passenger pigeon as far back as 1990.

I wish to thank for its scholarly hospitality the Department of Wildlife Ecology (as it was then), University of Wisconsin (Madison), where the papers of A. W. Schorger are housed; Professor Robert McCabe, the ornithologist and colleague of Aldo Leopold, was particularly helpful and encouraging. Thanks also to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia; the Department of Ornithology, Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto); and the ornithological library of the Natural History Museum, South Kensington (London). I am indebted to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Ottawa) for a research grant that enabled me to visit the institutions above. The Canadian Museum of Civilization helpfully answered my queries about scholarly sources pertaining to the role of the passenger pigeon in the lives of the native peoples. I would like to thank Charles Bolding for his research assistance. Pilgrims of the Air is dedicated to the memory of my friend and University of British Columbia colleague, the late Peter A. Taylor in whose kitchen, over the pages of Percy A. Taverners Birds of Canada (1934), the idea of the book was hatched.

Vancouver Belfast Skye

Contents

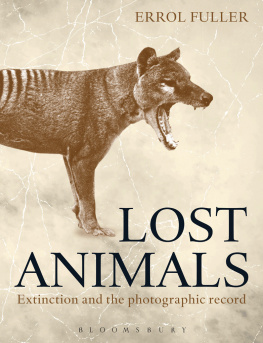

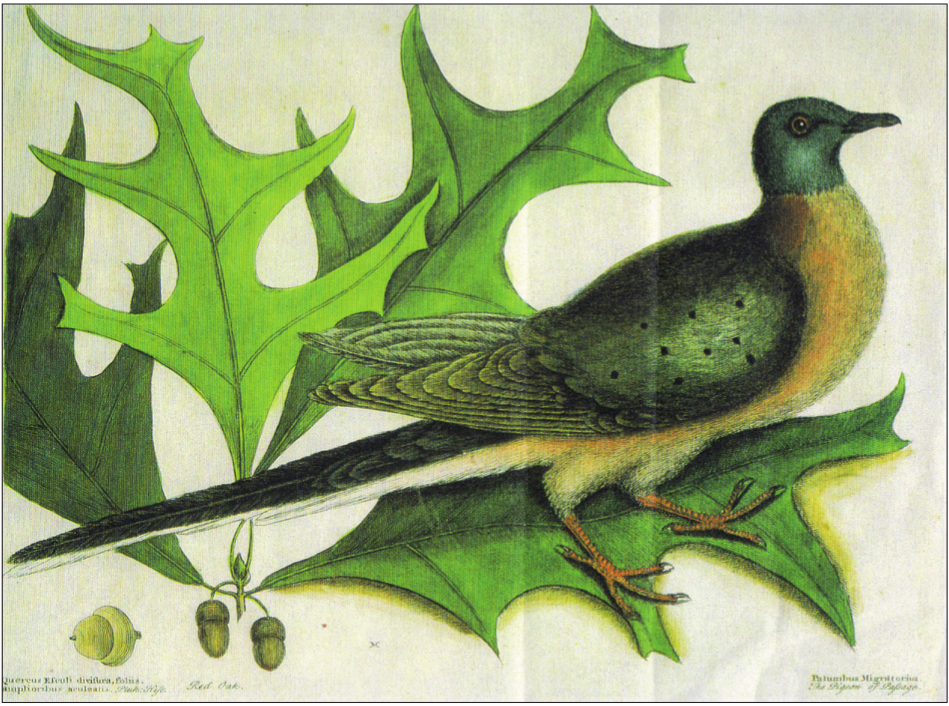

The posture Thoreau noted, captured by K. Hayashi in Whitmans Orthogenetic Evolution in Pigeons (1919)

Wonderfully prolific, having the vast forests of the North as its breeding grounds, traveling hundreds of miles in search of food, it is here today and elsewhere tomorrow.

Report of a Select Committee of the Senate of Ohio rejecting a bill proposing to protect the passenger pigeon (1857)

Now they was plenty of wild pigeons, now you show me any of them in these days. You dont hear of none or see none nowhere, do you? But they said they was plumb thick. When they was a good beech mast, they said, they was just plumb thick, they just come, just droves and droves of em. Said they just got plumb fat on that beech mast, now you dont hear of them anymore.

Burl Hammons (b.1908), West Virginia

Whatever I talk about is yesterday By the time I see anything it is gone

W. S. Merwin, Talking

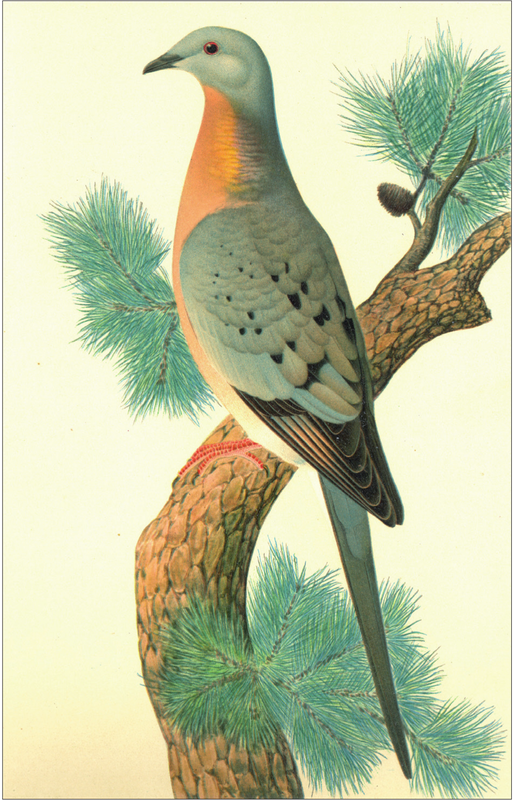

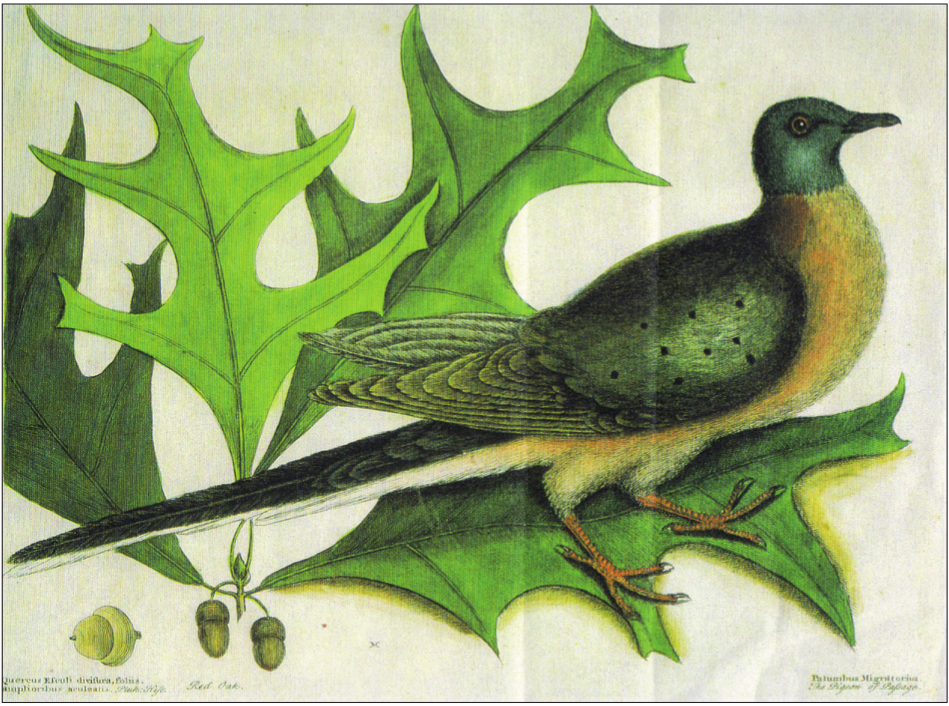

Mark Catesbys pioneering 18th-century depiction

I t is one hundred and sixty miles from Worcester, Massachusetts to Pleasant Valley, New York. Driving west on the I-90, then on Taconic Parkway, then west on US-44, one might take a little over two and a half hours to get there. It would have taken a great deal longer in 1911 when no parkways or freeways existed and a patchwork of railways competed for routes. Clifton Hodge in any case would have undertaken the arduous enough journey (perhaps of five hours or more) with an alloy of hope and resignation. He was on a wild pigeon chase and felt sure that it would turn out to be exactly that. He had not caught sight of the bird since a flock of about thirty birds flying south six years before had excited him so much he took off his hat and waved it, shouting, The passenger pigeons are not extinct! and then began a campaign to prove it beyond any doubt. Yet the most hopeful reports had to be followed up, it being a matter of life or death for the species.

And it was no ordinary bird; he thought it the finest breed of pigeon that had ever graced this undeserving world. In early May word had come in from Pleasant Valley of a tiny nesting colony of ten pairs. He could spot the dozens of false reports straightaway: the nests were in the wrong place, the eggs were of the wrong number, the birds behaviour was untypical. But this report required his travelling shoes.

When he got to Pleasant Valley he was met and taken to a clump of tall Norway spruces. True, the nests were at passenger pigeon height, thirty to thirty-five feet off the ground, but he sighed, knowing at once that here was merely an uncustomary colony of mourning doves. The mourning dove was the usual suspect when reports of pigeons came in: President Theodore Roosevelt had volunteered to help find passenger pigeon nests but what he found and forwarded were always dove nests. Hodge circled the trees, watched the doves, then went through the motions of climbing the trees and checking the nests. He knew the doves had inadvertently created this colony merely by having to crowd into a few isolated trees. They had probably built their nests unusually high because of the cats he saw malingering and because the drooping lower branches of the spruce had no horizontal support for the doves rickety platforms of twigs. The passenger pigeon was almost palpable in its absence. He shook hands with his informants, accepted their $5 forfeit fee, and retraced his steps to Worcester where he taught in Clark University, no closer to solving the passenger pigeon problem. All of eighteen months before, he had made it clear he could not blame anyone who lost hope that a wild member of the species existed anywhere on the North American continent.

The problem, as he had called it when he addressed the American Ornithologists Union (AOU) in New York City in December 1909, was how to explain not just the disastrous collapse of the species but the failure to find nests even while apparently reputable sightings were reported. Perhaps the dollar incentive needed to be raised; certainly it needed to be swung in another direction. The businessman and philanthropist Colonel Anthony Kuser had offered $100 for the discovery of any surviving representative of the Passenger Pigeon (as the AOU rather legalistically put it). This included the fresh carcass of what had been a surviving representative of the species until the discoverer got it in his sights. Then the penny dropped that if theirs was an effort to preserve, not kill, the ways of the shotgun-wielding field-collector were inappropriate; the reward would become a bounty and some innocent or guilty party might claim $100 for the scalp of the very last passenger pigeon in the wild. Kuser withdrew his offer and replaced it with $300 (not far short of $7,000 today) for first information on a nesting pair of wild passenger pigeons (