i

donald culross peattie library

Published by Trinity University Press

An Almanac for Moderns

A Book of Hours

Cargoes and Harvests

Diversions of the Field

Flowering Earth

A Gathering of Birds: An Anthology of the Best Ornithological Prose

Green Laurels: The Lives and Achievements of the Great Naturalists

A Natural History of North American Trees

The Road of a Naturalist

ii

published by trinity university press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Compilation and revisions copyright 2007, 2013 by the Estate of Donald Culross Peattie

Copyright 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, and 1964 by Donald Culross Peattie

Copyright renewed 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, and 1981 by Noel Peattie

Foreword copyright 2007 by Mark R. Peattie

Introduction copyright 2007 by Verlyn Klinkenborg

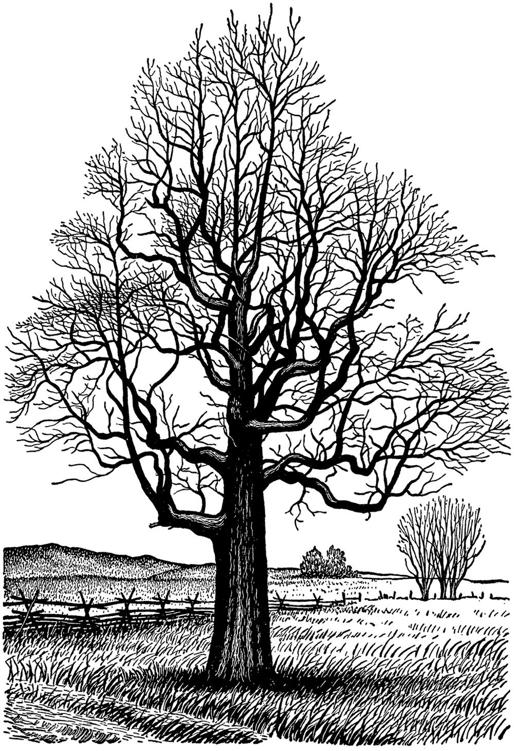

Illustrations copyright 1950 and 1953 by Paul Landacre

Illustrations copyright renewed 1977 by Joseph M. Landacre

ISBN 9781595341662 (paper)

ISBN 9781595341679 (ebook)

Cover design by Chris Hall

Cover illustration: Kazuhiko Yoshino/iStockphoto.com

Book design by Robert Overholtzer

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 39.48-1992.

CIP data on file at the Library of Congress.

17 16 15 14 13 | 5 4 3 2 1

xi

See him now, walking along some western trail. It can be anywhere in the lonely canyons of the San Jacinto Range, in the foothill chaparral behind his beloved Santa Barbara, or sauntering along the San Simeon Highway where the Santa Lucia Mountains, mantled in lupine and vermilion paintbrush, plunge precipitously into the Pacific. Or perhaps he strides along a path deep in the great redwoods, or pauses at the foot of the snow-covered Olympic Range in Washington to pick a flower among a small patch of moss laid bare by the midautumn sun.

But chances are that, whether he is wandering among the fan palms of the Mojave Desert or standing in the shade of a live oak in the Lompoc Hills, he will present a singular figure: a dark green Stetson on his head, a coat and tie he never went anywhere outside without them binoculars around his neck, and slung over his shoulder his dark green vasculum, that sturdy oval cylinder of metal in which he collects plant specimens. When he is not gazing at the far horizon, his eyes sweep the ground for California poppies and bluebells, or creosote bush and sage if his walks are in the desert.

If he is near home, he will bring back his floral treasure and will take out each captive and lay it between large, thick gray sheets of blotting paper to be placed with others in a stack pressed between two plates of slatted wood, the whole then stood on either by me or one of my brothers, while he buckles it tightly together. Days later, the blotters will be opened, releasing fragrances throughout the house, and the specimens labeled and carefully taped into a series of huge albums, which would xii come to constitute a veritable encyclopedia of western plants. (In the years to come the Peattie collection of western flowers and plants will become known throughout the botanical world, but their ultimate destiny will be a mystery.)

So, his sons came to know that kindly, searching figure as we grew up in various rambling homes in Santa Barbara, California. We learned to respect his hours in his study, the smoke curling up from his pipe as he sat in front of his typewriter producing the pages that so deservedly won him fame as one of Americas most cherished nature writers. He was ever the courteous, beloved, but slightly distant figure, even to his sons, and if he held to the habit of wearing a coat and tie, whether at dinner at home or on a picnic near a waterfall, it was only the physical manifestation of his courtly demeanor. As a neighbor once remarked to me, Your father has the manners of a Spanish ambassador.

His love of plants came early, and he sensed it first in the Appalachian Mountains where, as a frail young lad, he spent the winters to avoid the endless coughing fits brought on by the cold of Chicago. His fascination soon fixed on all that grew in those lush mountains. Family legend has it that, walking along a dusty road in the Blue Ridge of North Carolina, he met another boy carrying a gorgeous flowering dogwood branch with which the boy kept hitting his shoes to keep the dust off. Young Donald was so struck by the floral glory so callously treated, that on the spot he exchanged a brand new pen-knife with inlaid mother-of-pearl for the dogwood branch.

He tried his hand at other things, including two years studying French poetry at the University of Chicago, but his keen interest in living things always brought him back to the green world. So it was that he transferred to Harvard to study with Merritt Fernald, one of the greatest of Americas botanists. After some years working a desk in the Bureau of Plant Introduction in the Department of Agriculture, now equipped with both scientific training and the eye of poet, he turned himself and his talents loose upon the printed page. All aspects of plant life became matters of intense interest, study, and constant writing. He collected specimens in the Indiana dunes along the windy shores of Lake Michigan and turned out a small classic from his findings. He found wonder in pondering the algae of Archaeozoic times, in reflecting on the place of the lowly billions of tiny diatoms that form the bottom of the marine food chain, and gloried in the story of the great ferns of geologic times that laid down the coal seams that were to fuel a nation. More than occasionally he wrote of xiii the romance of plant life. He wove his magic in his account of the mystery of that delicate and long-lost flower, Shortia, found only in the inner recesses of the Appalachian mountains. His fascination with plant life extended to the kelp leviathans that form great marine forests off the California coast, an interest that, for a short time, was to drive his family to distraction since he filled every bathtub in our house with the seaweed he was studying.

Next page