Preface

Baseball histories take two shapes. First are biographies of great or controversial players or managers. The bottom line is that few, if any, baseball historians connect the dots.

For example, Jackie Robinson is said to have integrated baseball in 1947. Not many works connect those particular dots.

A few volumes do present retrospectives covering the sport overall. For example, in 2017 Yale University Press published Why Baseball Matters as part of series Why X [or Y] Matters .

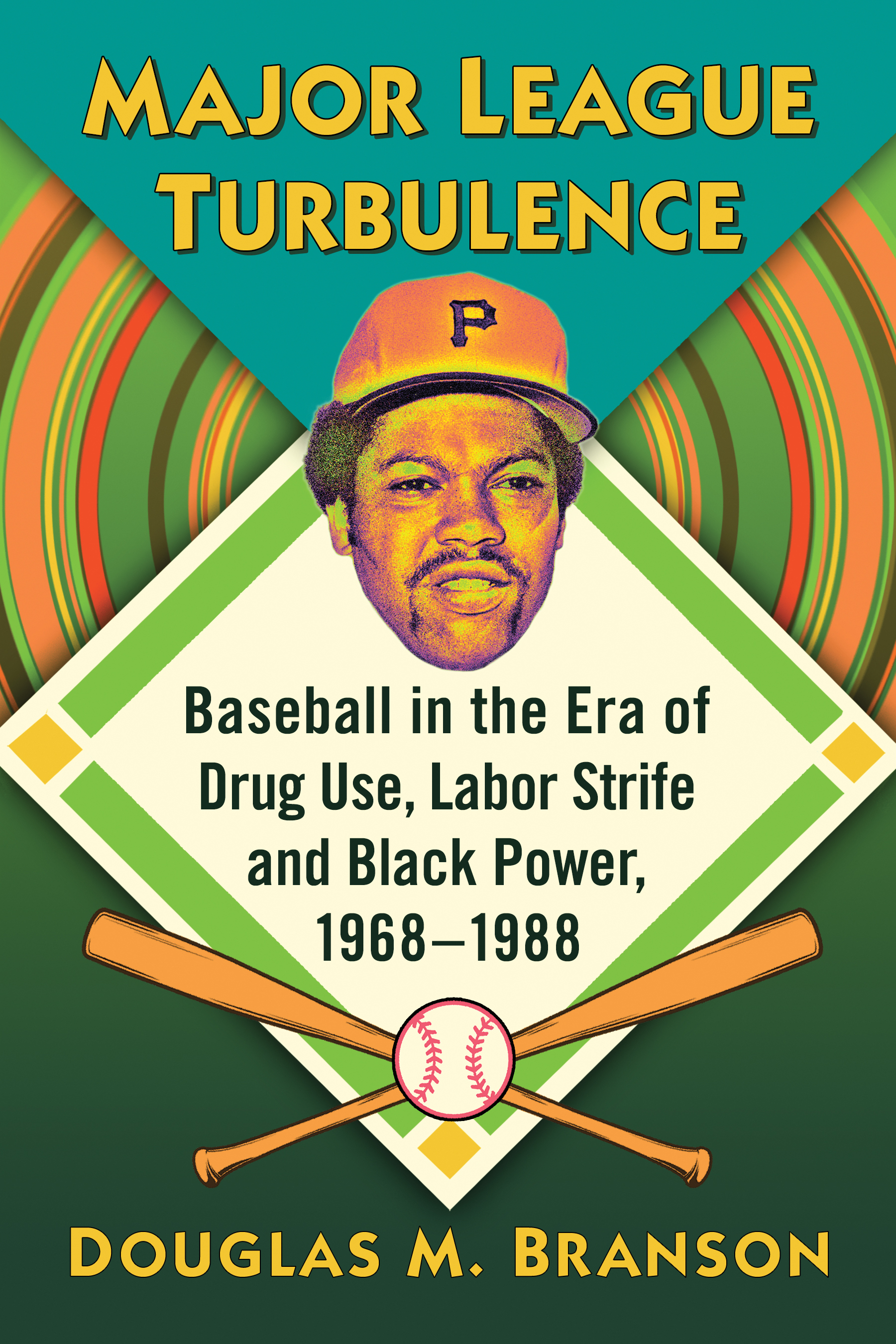

This book examines a period of time rather than one specific topic, attempting to connect the dots, from a period beginning with widespread questioning of authority, the Vietnam War, our societys segregated nature, and the involuntary servitude that characterized baseball. Treatment begins, then, with 1968 and the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. Again, the purpose is to relate in one place occurrences and careers previously left to discrete analysis rather than being treated as an interconnected whole.

In April of that tumultuous year, 1968, James Earl Ray assassinated Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to be followed two months later by Sirhan Sirhans assassination of Robert Kennedy. Earlier in 1968, the Tet Offensive brought home the futility of the Vietnam War, as the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese army were able to seize control of all South Vietnamese towns and cities. Later, on October 16, 1968, the 200-meter gold and bronze medal winners at the Mexico City Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, raised gloved hands skyward in a black power salute, framing an image that has become iconic.

Accounts of events continue through the early 1970s to baseballs infestation by pandemic recreational drug use, culminating in the Pittsburgh drug trials of 1985. In ensuing years, performance-enhancing drugs (steroids and human growth hormones) pushed recreational drugs onto the back burner, where they subsisted but did not disappear.

The original title for this book was Saints and Sinners (Mostly Sinners) in Modern Baseball. Sinners (rascals really), though, represent a broad topic, as there have been many in baseball. They include Shuffling Phil Douglas (Giants, 191422) or Paul The Dude Derringer (Cardinals, 193133, and Reds, 193342). They also include the famous: Battling Billy Martin, a player (Yankees, 195057) and manager (Twins, 1969; Tigers, 197173; Rangers, 197375; As, 19801982; and Yankees, 197578, 1979, 1983, 1985, and 1988),

Very early on, though, I identified two sinners or rascals who, at the times they played, were harbingers of things to come: black power, labor unrest, recreational drug use, and unbridled questioning of authority, in baseball as well as everywhere. Those late 1960s careers ushered in an era of turbulence in baseball, a microcosm that proved not to be exempt from the influence of external events even though the baseball establishment maintained otherwise. [At] that time [1968] in our country, things were as screwed up as they can be. As a ballplayer, you try to protect yourself by wrapping yourself up in the game, paying attention to nothing else, said Washington Senator Frank Howard. In 1968, and beyond, the barriers gave way. He continued, Things wormed their way inside you. My goodness, all the crap that was happening.

The two sinners I focused on played major league baseball, at a high level, in the two principal cities of Pennsylvania. He wore curlers in his hair; on one occasion he pitched a no-hitter, and Ellis later claimed to have been high on LSD; on another occasion he threw at the first five Cincinnati Reds he faced, hitting three of them, before Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh finally pulled Ellis from the game.

The second sinner, or rascal, on the opposite side of the Commonwealth, was Richie Call Me Dick Allen, known since birth and among friends as Dick Allen. Dick Allen was National League Rookie of the year as a Philadelphia Philly, where he played l96369 (and 197576), and American League Most Valuable Player (MVP 1972), hitting and fielding for the Chicago White Sox (197274). Allen had stops in St. Louis and Los Angeles in between. He never had a stake in the ground anywhere he played, save in Chicago, for one year or so. There he also was the most imposing, game-changing major leaguer I personally have ever seen, which I did as a White Sox fan in 1972. Allen waved a 42-ounce baseball bat around as though it were a toothpick, that year hitting .308 with 37 HRs, 113 RBIs, and an OPS of 1.023. He also stood out as an advocate for players rights, for players salaries, and as a militant African American.

Movie producers and directors speak of dressing the set before filming a motion picture. A baseball book should do the same. Chapter 1 dresses the set, reviewing baseball after the cataclysm of World War II ended and on into baseballs golden years, the 1950s. Chapter 2 finishes off the prelude with material describing the first half of the 1960s. Author Michael Leahys recent book, The Last Innocents , is one volume delving extensively into baseball and its surroundings during 196065.

Those halcyon days, though, left detritus that has been noted only episodically or has remained unmentioned. First is the presence of alcohol abuse among the players, a subject merely skimmed in many historical accounts. Second is the painfully slow and stop-and-go nature of integration. There are claims that, in 1947, Jackie Robinson (Dodgers) and Larry Doby (Indians) integrated baseball. Thats the trouble behind baseballs 1950s dark side. Baseballs golden era had flaws, largely hidden or forgotten today.

The trouble ahead of the golden era was the pervasive and growing use in baseball of amphetamines (uppers, or greenies) in major league clubhouses, dugouts, and bullpens, a precursor perhaps of the widespread recreational drug use that plagued baseball in the 70s and 80s. Alcohol abuse, enhanced by long train rides and time in bar cars, was hidden from public view but was rampant, nonetheless.

When I left the college campus in 1965, male students wore madras shirts, cotton khaki pants, and penny loafers. The most popular haircut of the day just shy of a crew cut was called the Princeton. When I returned from my year (May 1966 to April 1967) in Vietnam, everything had changed. Long hair, beards and moustaches, bellbottoms, flowered shirts open to the waist, easy sex, and smoking marijuana (dope) were everywhere. The Summer of Love took place in 1967. In droves, young people protested against the Vietnam War and President Lyndon Baines Johnson (Hell, no, I wont go; Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?; Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, the NLF Is Gonna WinNLF being the abbreviation of the formal name of the National Liberation Front, known as the Viet Cong). Youth questioned authority in every instance in which it attempted to manifest itself. Young people questioned parents, teachers, police officers, judges, politicians and anyone else who said either this is so or do this or dont do that. The self-assertiveness seen in four-year-olds had grown exponentially amongst young adults.

Few in baseball epitomize those developments in our society overall, from 1968 to the late 1970s, better than Dock Ellis and Dick Allen do. So chapters 4 through 10 beat that drum. Ellis, in particular, used recreational drugs, heavily in fact, and forms a bridge to the next era in baseball, the PED (performance-enhancing drug) era. Dick Allen was not a drug user (or abuser), but he became a talisman for the labor unrest and the rise of black power that permeated the 1970s and 1980s.