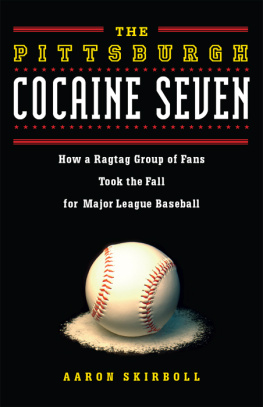

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Skirboll, Aaron.

The Pittsburgh cocaine seven : how a ragtag group of fans took the fall for major league baseball / Aaron Skirboll. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56976-288-2 (hardcover)

1. BaseballCorrupt practicesUnited States. 2. Baseball PennsylvaniaPittsburgh. 3. Pittsburgh Pirates (Baseball team). 4. Baseball playersDrug useUnited States. 5. Doping in sports

United States. I. Title.

GV863.A1S436 2010

796.357640974886dc22

2010004179

Interior design: Monica Baziuk

2010 by Aaron Skirboll

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-156976-288-2

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

F OR MY WIFE, JAMIE.

B ASEBALL HAS FALLEN.

B ARKED CHINS AND BROKEN FINGERS

MAY BE EASILY MENDED,

BUT A DISFIGURED REPUTATION

MAY NEVER BE ENTIRELY REPAIRED.

H ENRY C HADWICK

(18241908),

SPORTSWRITER AND HISTORIAN

Contents

P ROLOGUE : T OUGH T ALK

PART I 1979CITY OF CHAMPIONS

T HE L ONER M EETS THE S TAR

S TRUNG O UT

T HE U NITED S TATES V ERSUS C URTIS S TRONG

P OSTGAME

P ROLOGUE

Tough Talk

T HE WORDS rang clear. Somebody has to say enough is enough against drugs. Baseballs going to accomplish this, the commissioner claimed. Were going to remove drugs and be an example.

It sounded like the head of baseball was finally getting tough about drug use in his sport. But this declaration came not from the ninth and current commissioner Bud Selig, talking about the sensational steroid scandals that have rocked the last decade, but rather from baseballs sixth commissioner, Peter Ueberroth, during a commencement address at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. The year was 1985, and Ueberroth was talking about cocaine.

A federal investigation into possible drug trafficking involving major league ballplayers was coming to a close in Pittsburgh, and Ueberroth was steadying himself for the storm to come. Nobody knew exactly what would be revealed as a result of the investigation, but it was speculated to be big. Some of baseballs brightest stars had been seen in recent months coming to and going from Pittsburgh, only this time they werent in uniform, and they werent headed to the stadium. Instead, they were wearing thousand-dollar suits and speaking in front of a grand jury at the U.S. District Courthouse on Grant Street. Indictments were expected back any day.

Commissioner Ueberroth went even further, declaring that random drug urinalysis tests would be administered to all baseball personnel. Owners, batboys, secretaries, and all minor league players would be tested. There was only one exceptionthe major league ballplayers themselves. They would be excluded for now, because mandatory drug testing for them would have to be agreed upon by the players union. Ueberroth was hoping to persuade the players to test voluntarily.

The interim Major League Baseball Players Association executive director at the time, Donald Fehr, dismissed Ueberroths act as nothing more than grandstanding. And with everyone awaiting word from Pittsburgh, Fehrs position certainly had merit. The commissioner surely couldnt feign ignorance; he had to get in front of the potential scandal, which he attempted to do with his purposeful statement.

Finally, on May 30 and 31, 1985, the investigations targets were revealed when seven indictments came back from the grand jury. Major League Baseball officials could breathe a sigh of relief. The authorities were going after not the players but the dealers, a ragtag group of seven local men. The Pittsburgh cocaine seven consisted of a pair of heating repairmen, an accountant, a bartender, a caterer, a land surveyor, and an out-of-work photographer. Collectively they could be seen as nothing more than an assortment of sports groupies.

In September 1985, under the spotlight of the national media, the first of a series of trials that became known as the Pittsburgh drug trials began. In the history of baseball scandals, these trials represent the bridge between the 1919 Black Sox scandal and the steroid era that came to national attention in the 1990s. At the center of the proceedings was United States v. Curtis Strong, the biggest drug trial in major league baseball history.

Whispers about cocaine use within the league went back almost five years. However, as happened in Kansas City in 1983, when four players were arrested on cocaine-related charges, guilty pleas or plea bargains always served to shield the athletes involvement from the public eye. The Pittsburgh drug trials blew a hole through such secrecy. Covered by a blanket of immunity, seven active and former major league players came before the court to admit their transgressions through testimony more detailed and sordid than anyone could have imagined.

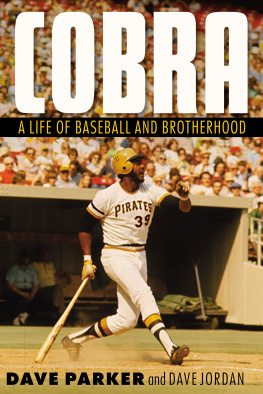

The Pittsburgh Pirates were inextricably involved in the scandal. The sensational trials were the culmination of a story that began in 1979, the year the Pirates sat on top of the baseball world and lifted the whole city along with them. Pittsburgh was known as the city of champions. Six years later, the Pirates had become the laughingstock of the league and nearly left town after being sold to new ownership. The teams home, Three Rivers Stadium, became known as the National League drugstore. And once again, the city was taken along for the ride.

The Pirates story can be seen as a microcosm of what was occurring on a much broader scale throughout the league. Contrary to Commissioner Ueberroths grand statements, Major League Baseball did not set an example for eliminating drug use in sports. The players testimonies of widespread cocaine and amphetamine use before, during, and after games should have been the catalyst to usher in major policy changes. The trials offered a brief moment when the issue was out in the open. Drug testing was talked about relentlessly, and coming out of the events in Pittsburgh most baseball observers considered it a foregone conclusion that a testing program would be implemented. Cocaine should have saved the league from steroids. Instead, league officials dropped the ball, sweeping the problem under the rug and leaving the door ajar for future scandals.

Nearly twenty years passed before the league addressed the issue of drugs in baseball, when a new era of steroid use created robotic home run machines disguised as flesh and blood. Along the way some of the games most cherished records were broken. As a result, skewed and meaningless statistics have shaken a sport in which numbers are the backbone of the game.

In 2006 Bud Selig, pushed by the controversy surrounding Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williamss groundbreaking book Game of Shadows: Barry Bonds, BALCO, and the Steroids Scandal that Rocked Professional Sports, as well as government interest, enlisted former U.S. senator George J. Mitchell to investigate the use of illegal, performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) within the major leagues. A year later, presented with the results of the four-hundred-plus-page report, Selig stood up and, like Ueberroth, talked tough: Our fans deserve a game that is played on a level playing fieldwhere all who compete do so fairly, he said. So long as there may be potential cheaters, we will always have to monitor our programs and constantly update them to catch those who think they can get away with breaking baseballs rules. In the name of integrity, thats exactly what I intend to do. Major League Baseball remains committed to this cause and to the effort to eliminate the use of performance-enhancing substances from the game.

Next page

![Garland - Willie Stargell [eBook - Biblioboard]: A Life in Baseball](/uploads/posts/book/173641/thumbs/garland-willie-stargell-ebook-biblioboard-a.jpg)