Contents

I very rarely make plans for my writing; I admire thriller writers who paper the wall with Post-it notes and science fantasy authors who make spreadsheets and histories for the worlds theyre creating. Even when Im writing something that should be planned, like a radio play, I just crack a cup of tea over the vessel of my ideas (its too early in the morning for champagne) and set sail on an uncharted voyage. This has meant that the producers and directors have had to work very hard with me to help me to produce something that has plot and character rather than images and gags and so with this new book I decided Id learned my lesson and I would make a plan. Maybe I wouldnt go as far as spreadsheets, but I would certainly have a compass. A metaphorical compass, of course, but it would be a start.

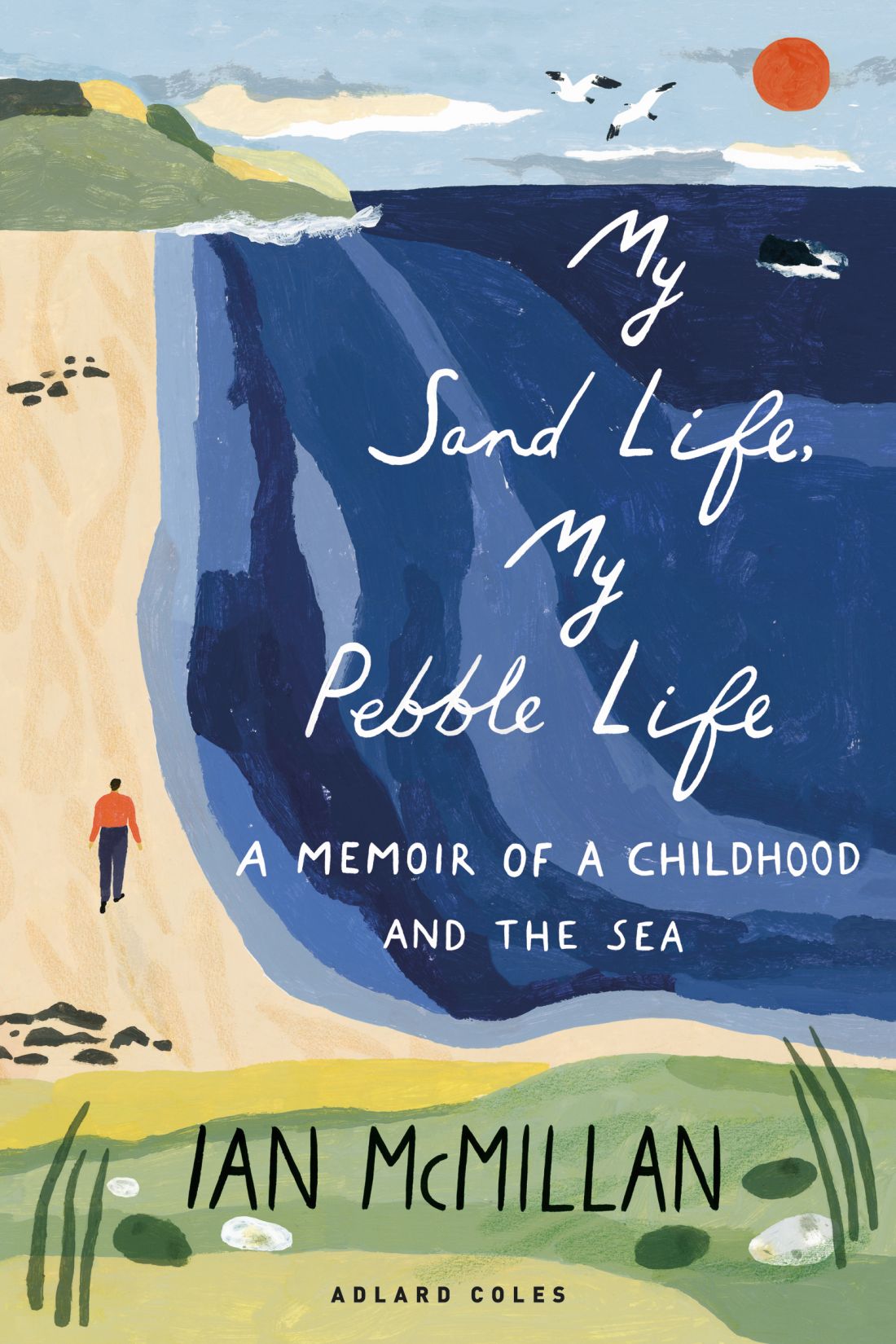

The idea of the book was that I would write about the coast of Britain; sometimes I would delve into my memories of places Id visited, and sometimes I would visit new places and write about what I encountered. I would try and knit connections between the two and, like all writers unless theyre liars, I would imagine the author photograph of a windswept me gazing out at the eternal water, perhaps with an ironic ice cream in my hand.

My plan for the book was based around my quest to do a gig in every village hall in the country with my musician mate Luke Carver Goss. If the coast was within striking distance, by which I mean of a railway because I cant drive, of the village hall wed played the night before, I would go there the next day and absorb it on the (metaphorical again) blotting paper I wrote on. This may not seem like much of a plan if youre a thriller writer on the fourteenth book of a series featuring a hard-bitten detective with a complex home life and a passion for vintage china but let me tell you that for me its a plan.

And then the pandemics tide started to come in. In early March 2020 my wife and I had a couple of days in Scarborough, the jewel of the East Coast; the plan was that this would make the first chapter of the book. Except that things felt a little chilly, and that wasnt just the wind blowing across the sand. We went into shops to try to buy hand sanitiser but there was none. People looked nervous; there seemed to be a sense of hurry about them as though they wanted to rush somewhere but, crucially, they werent quite sure where. In our Premier Inn there was no buffet breakfast and we were served by a waiter who said This is how it will be for a little while and I felt a deep sadness, partly because of his turn of phrase and partly because I couldnt get seven sausages, a croissant and a tub of Greek yoghurt. After all, like everybody else in the Western world, Id become used to treating life as a buffet that endlessly invited me to graze. My wife and I felt a desire to sit far away from strangers and closer to each other. Walking towards the castle, we wondered aloud to each other whether we should have come. The strong wind made me weep. I think it was the strong wind.

And then, about a week after we came back home and I shook the sand out of my notebook, the country locked down and all my gigs fell off a cliff and my diary relaxed in its emptiness and lack of scribblings. The village halls of Britain were safe from my laboured gags. My children and grandchildren could no longer visit the house and we had to make do with drive-by wavings and Zoom quizzes that nobody really wanted to win. I still wanted to write this book, so I had to have a new plan, and the new plan was to use the time to climb deeper into my memories of the coast, of the places Id been and the person I was when I went there. Two slices of the coast would loom large: Cleethorpes, where my wifes family have had a caravan for decades, and where my 92-year-old mother-in-law would happily spend all summer, until 2020 put a lock on all that and forced her into a foreshortened season where she darent go on a bus; and Northumberland, where my children have had wonderful times and where my wife and I have discovered solace and calm over the years.

Brief unlockings like the one in the summer of that year allowed us out and it meant the sea air in the sentences was fresh rather than air-conditioned by memory, but mostly I paddled in the half-remembered and, I admit, half-invented past. And so the coast became a place of legend and myth; its unchanging narrative of tides and whirling gulls shape-shifted into my own story, a story of someone who, in their mid-sixties, was being nudged into a state of endless reverie by the lockdowns and the pandemic. I found that because I wore my mask a lot, I couldnt wear my glasses as much as I usually did; the mask and my breathing steamed them up. I went to the opticians and she said that my eyes were improving; I asked how that could be possible, given my advancing age. It sometimes happens, she said in the half-darkness. I didnt question further but I reckoned it was because the turbulent times had turned my gaze inward, towards an internal and personal coastline.

So, if youre expecting a guidebook, look away now. If you want a map, I suggest that you make your own because I think youll know your roads much better than I do. Welcome to my coast; come with me and wander its paths. You might not find your way back home; Im not sure if I ever will.

I was fifteen years old and I was planning a trip to Blackpool with my mates Bards and Smalesy; we were an inseparable trio whose nights out mainly consisted of wandering around the mining village where we lived and ending up at the fish shop for some chips with bits on. The pit bus would pass like an image of a world that would never change because this was the 1970s and there were certainties scattered between the loud revolutions and thinking that excited our young and impressionable minds.

In a complex domestic arrangement, Bards lived with his grandma near Barnsley and his parents lived in Blackpool; this was so that Bards could finish his schooling and not have his education disrupted, which made sense to us all as an idea because living with your grandma felt like fun and she certainly didnt mind him being out eating chips on a school night.

One Monday evening he announced that his parents had invited us to stay in Blackpool for a few days and that his dad would come and pick us up and take us after school on the coming Friday. I was suddenly overcome with an emotional and romantic idea: Ill tell you what, lads, I said (imagine my voice still breaking, still tinkling like glass, still warbling like a harmonica under water), lets stay up all night and walk to the beach to see the sunrise. They nodded and then Smalesy said, And lets do it in bare feet. Ah, the early 1970s: historys tie-dyed bucket, half full of hope.

At Maison Bards, we decided to do the all-night adventure on our third night; the first night was spent hunting for decent chips and avoiding gulls. Of course the chips were excellent because we were by the sea but of course we said they were inferior because we were teenagers from Yorkshire. The second night we thought wed just stay in watching Dr Who on TV because, yes, we were teenagers from Yorkshire. On the fourth night wed got tickets to see the hippy musical Hair at the theatre; it seemed that Bards had convinced his parents it was a family saga about barbers, which was fine by us because we were looking forward very much indeed to the nudity. It was the Age of Aquarius, you know; we could pretend we were seeing the show and the sunrise in California.