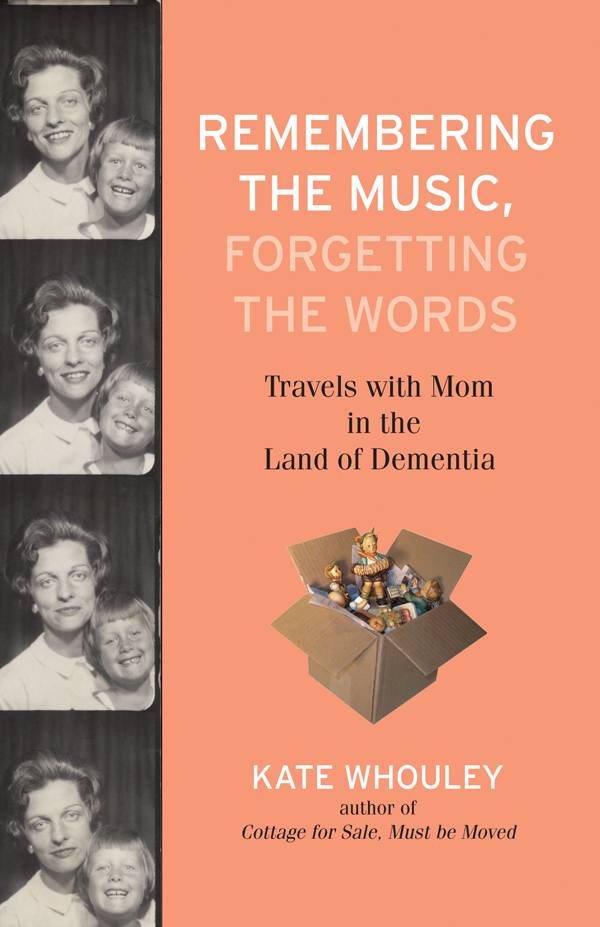

Remembering the Music,

Forgetting the Words

Travels with Mom in the Land of Dementia

Kate Whouley

Beacon Press, Boston

For Jack

Contents

Chapter One. What We Dont Know

I dont know my mother has Alzheimers.

What I dont know, what she will never knowsoon it will be killing both of us. But not quite yet. On this particular day, we are in the time and space that, soon enough, I will think of as before . We are unknowingmy mother and Iand we are happy.

Todaya late May Saturday in 2004my first book will be launched with a party at a venerable Cape Cod bookstore. You can find Titcombs Bookshop by looking for the man out front in the tricornered hat. Ted, son of Ralph and Nancy Titcomb, made the man in art school and placed him in his parents front yard, which also happens to be the front yard of the bookstore. Positioned near the bookstore sign, the wrought-iron gentleman carrying a walking stickand, of course, a bookhas become something of a landmark on scenic Route 6A. Im not sure anyone knows who he is supposed to be. Ben Franklin? Daniel Webster? Does his red coat suggest he is British? Nor do many folks know why hes there. But if you suggest meeting at the bookstore with the statue of that colonial guy out front, pretty much everybody who lives herebook reader or notknows just where that is.

Before the party begins, youll find me in and out of the Titcombs kitchen. I am accompanied by my stepsister, Vicki, and her partner, Martha. We are delivering beer and May wine, platters of fruit and cheese, toothpicks with miniature whirligigs attached to one end, boxes of crackers, bags of ice, paper plates, napkins, and a giant sheet cake frosted with an image of the book jacket. Were expecting 85 guests, based on the RSVPs to the 131 invitations I sent out about a month ago.

In a red silk V-neck and a voluminous black parachute skirtboth unfortunate choices for the photos my friend Anne will insist on takingI am not dressed like a bride, but the planning and execution of this event has felt a lot like managing a wedding. I swear thats why my uncle Jack offered to pay for hotel rooms for family members who wanted to come to the party. Hed done the same a year earlier, when my cousin (his nephew) Josh married Cindy in a breathtaking setting way the hell up in the mountains of Vermont. I am now forty-five years old, unmarried, and without a date for my own party. Jack, I am pretty sure, has deduced he is unlikely to walk me down the aisle. In lieu of giving away the aging bride, he would make it possible for far-flung family to come to my book party.

Vicki and Martha arrived late Thursday, driving seven hours from Bangor, Maine. On Friday they ran errands, picked up food and beverages, and figured out how to fit everything into my already overloaded refrigerator. They were the perfect bridesmaids. The maid of honor for my Book Wedding is my dear friend, Tina. She arrived Friday night in time to nurse me through my predictable wardrobe crisis. After deciding the black palazzo pants and lacy zip-up top Id planned to wear would be too hot and too dressy, I splurged on an alternative outfit at a Hyannis boutiquethe kind of place where the owner can convince you that you look amazing, and some of the time, you do.

Does this shirt make me look completely top-heavy?

Tina, stretched out on my bed, told me that I had a great top, that I should be proud of it. My friend and I nurture a mutual admiration of our differences. She wishes for a fuller bust; I wish for her neat figure. I wish for curls in my hair, while she wishes for the straightness of mine. Our friendship runs much deeper, but the mutual admiration of our inverses makes both of us feel better.

The planning and attendants may suggest alternative wedding, but in terms of momentous, life-changing events, this party celebrates my best entry yet in the category of child substitutes.

If you dont give me grandchildren, my mother once said to me, give me books. I was in my mid-twenties at the time and, I believed, more apt to have children than to birth books. It seemed to me a weird thing to sayand premature. I was just out of a six-year off-again, on-again relationship with my college sweetheart, but I didnt consider myself ineligible for a future relationshipor a family.

Huh? I managed.

Not everyone has children these days. Though it would be nice if you found someone and got married. Id like grandchildren. But if you wrote a book or two instead, that would be okay with me.

My mothers willingness to embrace literary progeny was no doubt rooted in her working life: she was first a high school English teacher and later the coordinator of English for her school system. It was a job she was born to do and a job she very nearly didnt get. We had moved just the year before, and she was new to the department. She was younger than the other candidates and the first woman to apply for a coordinator position in the system.

My mother knew she wouldnt win a popularity contest with her colleaguesmen or womenby refusing to accept the status quo. But she believed she was qualified, deserving of consideration, and only coincidentally female. When she was not invited for an interview, she did not accept her fate. She wrote letters, made phone calls, and asked for a meeting with superintendent. Finally she was told she could appear before the school committee to be interviewedat midnight on a school night.

Picture it: a midnight interview, grudgingly granted, with every person in the room viewing you as nothing more than a loudmouthed thorn in his side, resenting your persistence, your very presence in the room, not to mention your sex. And its been, after all, a long night, and goddamn it, cant we just get this coordinator thing over with? Enter my mother: striking, young, with a trained voice that projects from her diaphragm as she makes a killer presentation, outlines a bold new direction for the English department, a direction that will position the school system as an educational leader, a direction that will lead to commendations and awards and grant money.

Sometime in the wee hours of the morning the vote was taken, and my mother was the new coordinator of English.

I was not yet twelve years old when my mother got that job, but the way she fought for itand wonis absolutely tangled up in who I am today. She was my heroine in those dayswe were on our own, and she was an accidental feminist icon. I was proud of my mom, proud of her job, and proud of her polyester pantsuits.

Today, the Welcome Day for her first grandbook, my mother is subdued. Shes leaning on Bills elbow, smiling and making polite conversation as folks approach her. She makes no effort to circulate. I know that her arthritic hip is probably bothering her. But thats not the whole story. My mom hasnt been herself since the cancerbreast cancer. Surgery, radiationno chemo, because she has a chronic kidney condition. They found it earlystage oneand almost two years have passed since she finished her treatment. She is cancer free. But it isnt just the cancer that is gone. Some of the grit that got her that job, some of the spark and the mischief that won over her reluctant colleagueshell, even some of the sarcasm I have not always appreciatedhave departed with those poisoned cells. As I watch her from across the room, I have this unshakable sense that my real mother is not here.

Pushing that thought aside, I position myself in the far corner of the bookstore, at the book-signing table that has been set up for me. In my life as a bookseller, I hosted many authors, passing the books, open to the title page, to such literary luminaries as Doris Lessing, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Andre Dubus. Once, I provided Powdermilk biscuits for Garrison Keillor. Sitting behind the author desk today feels exciting, and also odd. But at least I know what to do.