978-0-674-97669-6 (alk. paper)

Names: Eichhorn, Kate, 1971 author.

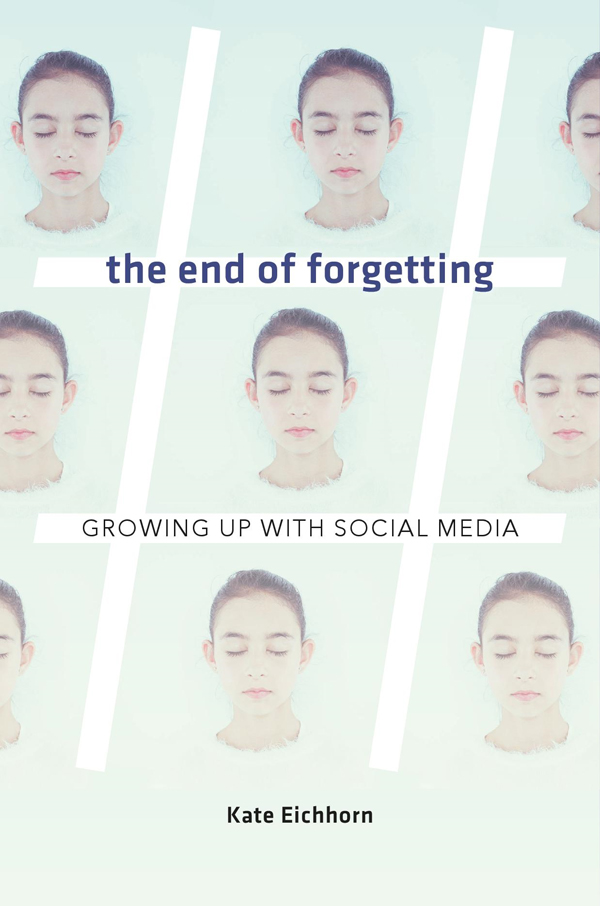

Title: The end of forgetting : growing up with social media / Kate Eichhorn.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : Harvard University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: LCSH: Social mediaPsychological aspects. | Online identities. | Internet and children. | Internet and youth.

I n the twentieth century, if one was truly mortified by a photograph from childhood or adolescence, there was a simple solution: secretly slip the photograph out of its frame or the family photo album and destroy it. In seconds, a particularly awkward event or stage of ones life could be effectively erased. The photographs absence might eventually have been noticed, but in the analogue era, unless ones relatives were fastidious enough to preserve the negative, one could be more or less assured that once the photograph was ripped up or burned, this embarrassing trace of the past had vanished. Without the photographs presence, one could also assume that any lingering memories of the event or stage of life would soon fade in ones own mind and, perhaps more importantly, in the minds of others. In retrospect, this vulnerability to human emotionto the shame and anger that once led us to destroy photographs with our bare handsmay have been one of the great yet underappreciated features of analogue media.

Several decades into the age of digital media, the ability to leave ones childhood and adolescent years behind, along with the likelihood of having others forget ones younger self, are now imperiled. While young people may still covertly attempt to delete photographs of themselves from their parents and grandparents mobile phones, tablets, and computers, that act is in no way akin to ripping a photograph out of an album and tossing it into the fireplace. It is nearly impossible to know whether the image is gone for good. Does the embarrassing photograph exist on only a single device? Has it already been shared with dozens of friends and relatives? Did anyone find it cute or amusing enough to post on Facebook? Where has the photograph circulated? Could all the copies be retrieved and destroyed? Worse yet, was the photograph tagged? An act of destruction that once took mere seconds is now a massive and nearly impossible undertaking.

Of course, it is unfair to blame this current phenomenon on the digital hoarding of doting parents and grandparents. After all, children and teens are now generating their own photographs at an unprecedented rate. Although exact numbers are hard to come by, it is evident that a majority of young people with access to mobile phones take and circulate selfies on a daily basis. But what is the cost of this excessive documentation? More specifically, what does it mean to come of age in an era when images of childhood and adolescence, and even the social networks formed during this fleeting period of life, are so easily preserved and may stubbornly persist with or without ones intention or desire? Can one ever transcend ones youth if it remains perpetually present? These are the urgent questions that this book seeks to explore.

From the Disappearance of Childhood to Perpetual Childhood

The crisis we face concerning the persistence of childhood images was the least of concerns when digital technologies began to restructure our everyday lives in the early 1990s. Media scholars, sociologists, educational researchers, and alarmists of all political stripes were more likely to bemoan the loss of childhood than to worry about the prospect of childhoods perpetual presence. In 1994, as the general public was just beginning to understand and absorb an entirely new vocabulary that included concepts such as the Internet, cyberspace, and the World Wide Web, I was beginning my graduate studies in the field of education. Educational researchers at that time were obsessed with measuring, monitoring, and debating the impact of the internet on youth and, more broadly, on the future of education. My supervisor, whose previous work had focused on the history of literacy, encouraged me to throw away my books, learn to code, and start researching and developing educational video games for the future wired classroom. Her optimism was unusual. A few educators and educational researchers were earnestly exploring the potential benefits of the internet and other emerging digital technologies, but the period was marked by widespread moral panic about new media technologies. As a result, much of the earliest research on young people and the internet sought either to support or to refute fears about what was about to unfold online.

Some of the early concerns about the internets impact on children and adolescents were legitimate. The internet did make pornography, including violent pornography, more available, and it enabled child predators to more easily gain access to young people. Law enforcement agencies and legislators continue to grapple with these serious problems. However, many early concerns about the internet were rooted in fear alone and were informed by longstanding assumptions about youth and their ability to make rational decisions.

Many adults feared that if left to surf the web alone, children would suffer a quick and irreparable loss of innocence. These concerns were fueled by reports about what allegedly lurked online. At a time when many adults were just beginning to venture online, the internet was still commonly depicted in the popular media as a place where anyone could easily wander into a sexually charged multiuser domain (MUD), hang out with computer hackers and learn the tricks of their criminal trade, or hone their skills as a terrorist or bomb builder. In fact, doing any of these things usually required more than a single foray onto the web. But that did little to curtail perceptions of the internet as a dark and dangerous place where threats of all kinds were waiting at the welcome gate.

While the media obsessed over how to protect children from online pornography, perverts, hackers, and vigilantes, researchers in the applied and social sciences were busy producing reams of evidence-based studies on the supposed link between internet use and various physical and social disorders. Some researchers cautioned that spending too much time online would lead to greater levels of obesity, repetitive strain, tendonitis, and back injuries in young people. Others cautioned that the internet caused mental problems, ranging from social isolation and depression to a decreased ability to distinguish between real life and simulated situations.