Alternative Iran

Contemporary Art and Critical Spatial Practice

Pamela Karimi

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

2022 by Pamela Karimi. All rights reserved.

Publication of this book has been aided by grants from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of CAA and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Karimi, Z. Pamela (Zahra Pamela), author.

Title: Alternative Iran : contemporary art and critical spatial practice / Pamela Karimi.

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021051790 (print) | LCCN 2021051791 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503630017 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503631809 (paper) | ISBN 9781503631816 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Dissident artsIran. | ArtsPolitical aspectsIran. | Arts, Iranian21st century.

Classification: LCC NX574.A1 K37 2022 (print) | LCC NX574.A1 (ebook) | DDC 700.955/09051dc23/eng/20220517

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021051790

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021051791

Cover design: Rob Ehle

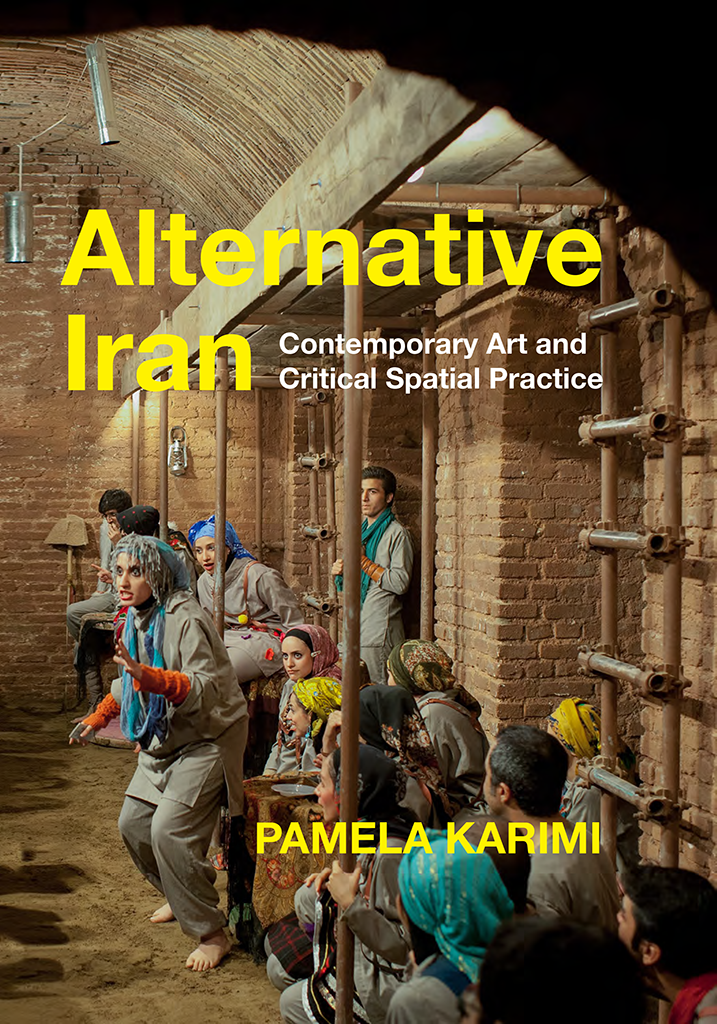

Cover image: Av Theatre Group, Melpomene, directed by Babak Mohri. 2013. Old underground thermal bath, Tehran. Photograph by Jeremy Suyker.

Typeset by Motto Publishing Services in 11/15 Minion Pro

To Robert

The best companion

Contents

INTRODUCTION

The Different Senses of the Alternative

FIGURE I.1 Av Theatre Group, Melpomene, directed by Babak Mohri. 2013. Old underground thermal bath, Tehran. Photograph by Jeremy Suyker.

IN FEBRUARY 2015 I came across a photo-essay on Irans Underground Art Scene circulating on social media. The work of French documentary photographer Jeremy Suyker, its cover image shows an experimental theater group performing in a disused underground thermal bath. I was struck by the spontaneity and expressiveness of the bodies of the performers interacting with their audience (

Looking at the people packed tightly into the abandoned subterranean vault, I was also reminded of the lived spaces of my childhood. During the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, my family took shelter in similar places. Some nights we slept under the main staircase in our house, clinging to the faint hope that the concrete structure would be the last thing to yield to the aftershock of an air strike. We lay jammed into the stair alcove, with the soffit so close it felt claustrophobic.

Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution that ousted Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi (hereafter, the Shah), the underground became part of the reality of our livesand not only in the form of domestic bomb shelters. After school, I would go to a class convened by my art instructor, Ali Faramarzi (b. 1950),blood red resonated with the war images that we saw on TV and in the propaganda murals and posters plastered all over the walls of our city.

Most of those who lost their university teaching posts because of their Western viewpoints or affiliation with the Shahs regime, which lasted from 1941 to 1979, had little choice but to give lessons in their homes (using public studio spaces as a formal place of education or a source of income was a challenging undertaking). Faramarzis painting class, then, was presumably among only a handful that operated in a public space. His sculpture class was another matter, as he would recall years later. Based on their interpretation of Islamic texts, religious scholars had dictated that sculpture was a forbidden medium, so all teaching sessions involving three-dimensional art had to take place in a more secretive locationin this case, the basement of the mall.

With the cooperation of the mall security guard, Faramarzi managed to keep the location of his teaching sessions under wraps. But he still had to take precautions. Girls and boys attended on separate days, and the only way to learn about these after-school painting lessons was through word of mouth; classes were not publicized at all. Indeed, private art studios were only fully recognized by the government after the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988. This was the sociopolitical milieu in which my generation learned about Western art, a topic banned in the government-run educational system.

That late afternoon lesson on Matisses Red Studio would be cut short by the earsplitting sound of air-raid sirens signaling the approach of Iraqi fighters. The lights went out and we rushed in a panic to the basement, running down the stairs in complete darkness with the thudding pulse of antiaircraft fire all around us. As we sheltered near Faramarzis stash of statues, I told a classmate how sorry I was that the Red Studio story had been interrupted. I was still feeling energized by the painting and wanted to know why Matisse had chosen to make his studio blood red. Appalled at my seeming unawareness of the danger we were in, she whispered, Well be lucky to get out of here alive.

Matisses Red Studio and endless nights sleeping in shelters are not just my memories; they are microcosms of a shared experience that continues to this day. While no conventional wars have been fought on Iranian soil since 1988, the threat of war has remained ever-present. The practice of art follows a similar logic. While efforts have been made to legitimize all kinds of art, many forms continue to be deemed inappropriate; regularly monitored, censored, or even banned by the government, they are often consigned to informal and unofficial spaces. Although Suykers photograph is of a sanctioned performance space, it nonetheless fully captures the mood that still prevails in Iranthe juxtapositions of excitement and fear, happiness and disappointment, stealth and openly passionate expression.

My reading of Suykers photograph might be interpreted as subjective, but familiar and cultural factors also mobilize this personal experience. To appropriate Roland Barthess words in Camera Lucida, Suykers photograph works as a sort of umbilical cord, [which] link[s] the body of the photographed thing to my gaze: light, though impalpable, is here a carnal medium, a skin I share with anyone who has been photographed.

In the same way, Irans nongovernmental art and cultural scenes are not only sites of personal encounters but also part of the collective experience of its citizens, and particularly of the artist community. This book sets out to provide an entry point into this experience without catering to voyeuristic curiosity or emphasizing the allure of what is already perceived as stealthy, illegal activity.

From the Underground to the Alternative

Some writers and journalists, especially if they live outside Iran, refer to postrevolutionary sites of nonconformist and grassroots activities as