Debra N. Mancoff

What makes a masterpiece?

What makes a work of art a masterpiece? The label is a mark of prestige, asserting that the work is the finest of its kind. As a material object, a masterpiece is seen to embody the spirit of an era and to exemplify the unique vision of an individual artist. It is also assumed to possess an intrinsic excellence that transcends time as well as national and cultural boundaries. A masterpiece wields an iconic authority; even if we have not seen the work, it lives in our visual imagination through reproduction, influence and imitation. To call a work a masterpiece is to declare that it manifests a universal and enduring power, and we accept this judgement, often without questioning the time, the taste and the circumstances that led to such high regard. But our admiration of a works greatness gives us no insight as to why it is considered great. Every work of art has a story, and the stories of the most renowned masterpieces reveal that making a masterpiece often involves much more than a demonstration of consummate artistic skill.

The use of the word masterpiece to indicate a standard of achievement has origins in the artisanal guild system of late medieval Europe. In those days, rather than marking a superlative achievement the best of its kind the production of a masterpiece proved that an aspiring craftsman had attained the body of knowledge and the necessary skills to present himself as a qualified practitioner in his chosen field. If members of the guild judged that the work demonstrated the requisite proficiency, the craftsman almost invariably a man would be awarded the status of master craftsman, and he would secure the right to open his own workshop, hire and train apprentices and to become a member of the guild. By the end of the fifteenth century, as the categories of fine art painting, architecture, sculpture began to be regarded as separate and superior to categories of craft building, metalwork, textiles the word master acquired the gloss of virtuosity. Within two centuries, art academies replaced the guilds as the preferred training ground for painters and sculptors, and although the practice of producing a work that marked the transition from trainee to professional endured, the work itself was more commonly called a diploma or reception piece. And, as the arts rose in cultural value, the term masterpiece came to define the highest possible standard of achievement: a designation of rare excellence above and beyond fundamental mastery.

As a term with a long history, the concept of a masterpiece also carries the burden of problematic presumptions. The exclusivity at its core is at odds with todays pluralistic art world. We no longer believe that works of art should conform to a singular standard or that they embody some inscrutable quality or intrinsic value that is timeless and universal in their appeal. We now celebrate how artists express the human experience in diverse ways, and we seek to broaden the ideas that inform the interpretation and evaluation of works of art. The word masterpiece contains troubling associations. It is an inherently gendered term inferring an established hierarchy, and it stirs up references to dominance and control: master and servant, or, even more unsettling, master and slave. And yet, the word still has relevance, for when a particular work of art is described as a masterpiece, it draws the publics attention. We want to observe and experience for ourselves those qualities that make it great.

How then to reconcile our contemporary questioning of the concept of a masterpiece with our fascination with works of art that seem to have timeless and worldwide appeal? The pages that follow offer a fresh approach to the understanding and appreciation of a selection of some of the most admired works of art through their origin stories stories that revisit the circumstances of creation and the rise of reputation. The featured works are all familiar; they enjoy wide popularity and critical acclaim. They each represent a turning point in the artists creative development and have come to be instantly recognized as his or her signature work. But these works also share a more intriguing common thread: their path to fame is only fully disclosed by looking beyond what the eye can see. Using primary documents to probe into each pictures past we can uncover the rich and often unexpected story behind their iconic imagery. Theft, scandal, legal disputes, politics and even defiance of the art worlds conventions have all played a part in shaping the perception of works that we now regard to be masterpieces. Rather than trying to discern and describe the elements of greatness, Making a Masterpiece takes account of the circumstances outside the frame that contribute to the perception of greatness and reveals that the journey from the easel to popular acclaim can be as compelling as the masterpiece itself.

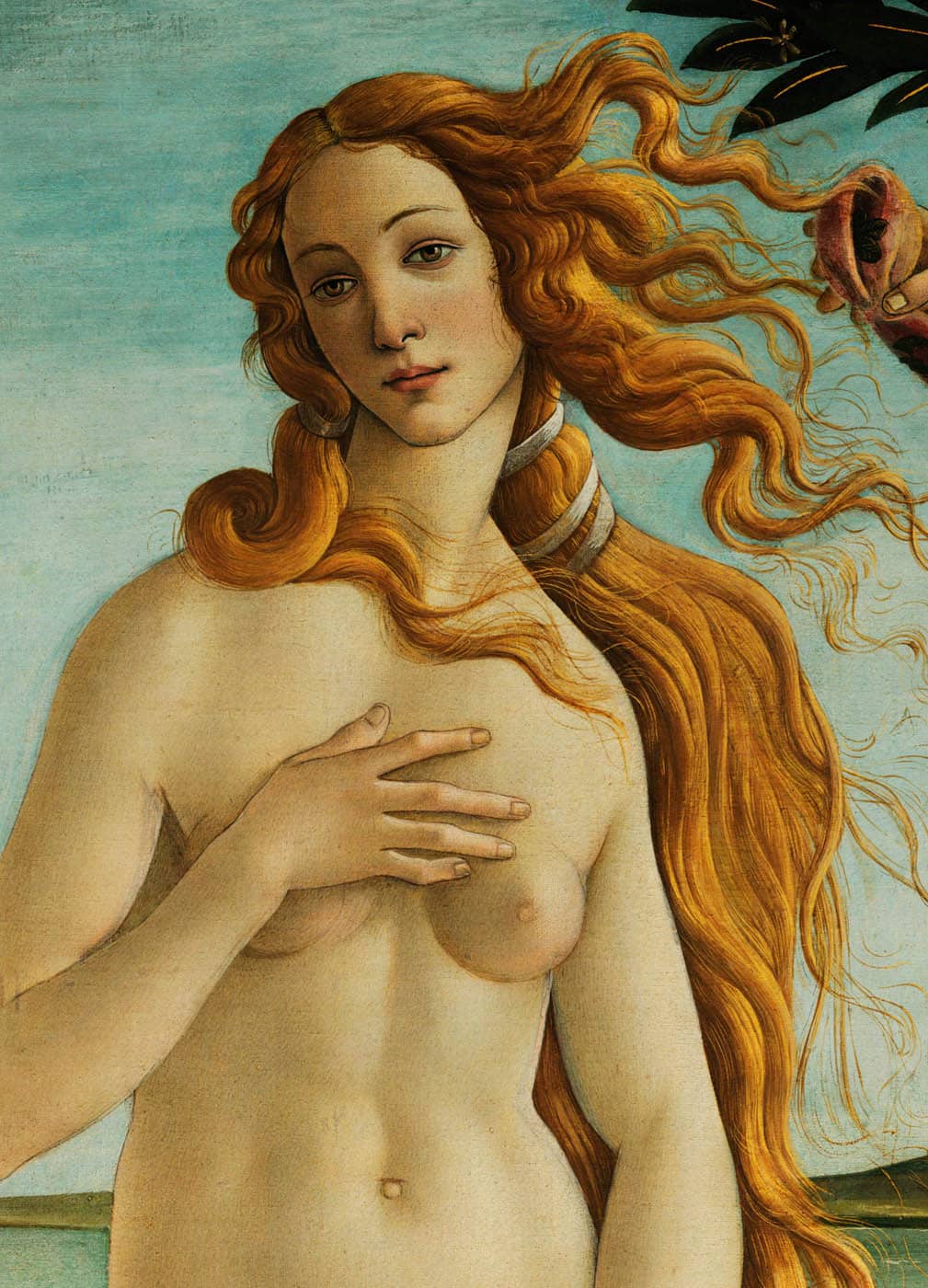

Birth of Venus

Sandro Botticelli

And borne there in gently pleasant movements, A girl of divine face,

Shore-ward driven by unbound winds, Drifting upon a shell, delighting the very heavens

Agnolo Poliziano, Stanze per la Giostra, 147578

On 1 January 1930, a memorable exhibition opened to London audiences at Burlington House. Organized by the Italian government, Italian Art 12001900 offered an unprecedented view of the nations treasures, including paintings, sculptures and jewellery, as proof of its enduring leadership in European culture. More than a desire to celebrate Italys rich artistic heritage, the enterprise was rooted in pride and conceived as propaganda to promote the public profile of the dictator Benito Mussolini as a man of refinement and taste. The location played a role in advancing Italys imperial ambitions for, as the head curator Ettore Modigliani explained, it was the intent of il Duce to mount an exhibition worthy of Fascist Italy in the capital of the British Empire. No matter the motivation, the critically acclaimed exhibition attracted more than half a million visitors before it closed on 22 March. Among the works that captivated the casual viewer and critic alike was one that had never been seen outside of Tuscany: Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli.

It is possible that more people saw Birth of Venus during its brief stay in London than over the previous four and half centuries. Seventy years passed between the presumed date of creation and the first known written record of the work, but its subject, style and subsequent history of ownership places it at the height of Botticellis career. Newly returned from a prestigious commission in the Sistine Chapel in Rome, Botticelli enjoyed the patronage of the Medici family, the leading and most generous art patrons in Florence. During the middle years of the 1480s, Botticellis work reflected the innovative philosophy of an intellectual circle also under Medici auspice. These were private pictures, endowed with esoteric meaning intended for an exclusive audience. Even after the work went on public display in the early nineteenth century it drew only limited attention. But with its debut in London,