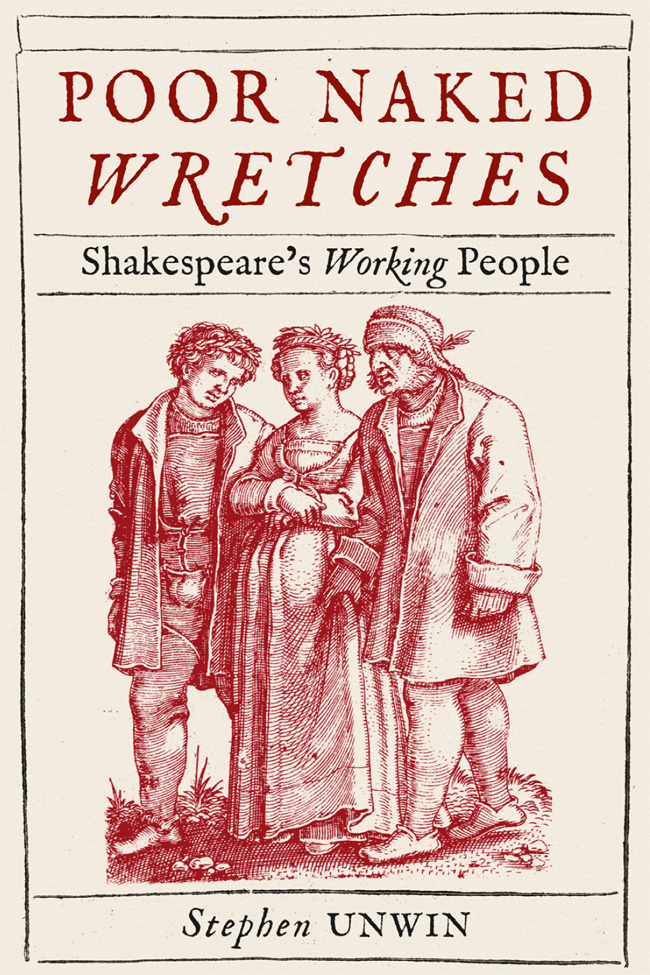

POOR NAKED WRETCHES

Jakob Binck, Farmer with a Basket of Eggs, 151069, engraving depicting a farmer, dressed in looped and windowed raggedness, taking his goods to market.

POOR NAKED

WRETCHES

Shakespeares Working People

STEPHEN UNWIN

REAKTION BOOKS

To

Ginny Schiller

Published by

Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2022

Copyright Stephen Unwin 2022

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain

by TJ Books Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN 9781789146622

C ONTENTS

Albrecht Drer, Peasant Couple Dancing, 1514, engraving. The irrepressible joy in being alive, whatever your social rank. The woman, however, is in charge, with her keys, knife and purse, as she gazes directly at us.

Preface

W AS SHAKESPEARE A SNOB? This book tries to answer this knotty question and, in the process, challenge some of the assumptions behind how his plays are read, taught and staged today.

The story starts one rainy afternoon almost forty years ago. I was directing a student production of The Comedy of Errors and was struggling with the scene in which the wealthy Antipholus of Ephesus, accompanied by his slave Dromio, invites two businessmen back to his house for dinner. He is shocked to discover his front door locked and another slave, also named Dromio, along with Luce the kitchen maid stubbornly denying them entrance. Nothing he can say or do persuades them to open up, and he is left humiliated and angry, threatening violence in the open street.

The scene seemed unnecessarily complicated. Everywhere I looked I saw characters pursuing their own interests, and I couldnt work out who the audience was meant to listen to or care about. But it suddenly struck me that this was the point: the kitchen maid is as interesting as the merchant, the goldsmith as three-dimensional as his customer, and while one slave comments satirically on his masters humiliation, his twin, like the all-powerful St Peter, has control of the gates. It was a eureka moment.

I encouraged my actors (the young Tilda Swinton, among others) to abandon any notion of a fixed social order, and express instead a cacophony of competing voices, fighting for status and advantage, joking and insulting, jostling and struggling to the bitter end. We did everything we could to ensure that the characters with the least social status were as demanding of the audiences attention as their (so-called) betters and relished the power that this temporary reversal afforded them. And soon the action felt as alive as the street outside.

The way we formulated it at the time was that on Shakespeares stage there was no hierarchy of reality, and that his vision of humanity was all-encompassing and indivisible. Everyone on stage is interesting, we agreed, and you shouldnt assume that those who speak the most are the most important, or that those in power are more interesting than those who arent. This is much more than the old theatrical adage that there are no small parts, only small actors; it is a re-evaluation of the playwrights attitude to the world. While some of Shakespeares characters might wield greater power than others, their creator saw them all as human beings, equal in the eyes of God, if not the society in which they lived. Or so it seemed to us.

Inevitably, we quickly discovered that these insights were hardly new. Hazlitt had got there first when he declared that Shakespeares genius shone equally on the evil and the good, on the wise and the foolish, the monarch and the beggar, and Brecht had observed Shakespeares commitment to contrasting class perspectives almost half a century before us. But this just confirmed us in our growing belief that every character in Shakespeare is of human interest, whatever class, education or role. And as an ambitious young director I was determined to explore this further.

On graduating, however, I was disappointed to discover how many theatre professionals focused their attention on the rich and powerful, the articulate and educated, and ignored or patronized the hundreds of working people who populate the plays and make such a contribution. And I was dismayed to observe that mainstream scholarship was so consumed by the increasingly fashionable questions of identity (above all, gender, race and sexuality) that poverty, labour and class were often overlooked.

In response, I directed a dozen professional Shakespeare productions for English Touring Theatre, the company that I founded in 1993, and tried to give these characters their due. I led workshops on Shakespeares Poor and taught the subject in drama schools and universities across Britain and America. And slowly, scene by scene, character by character, rehearsal by rehearsal, I gathered notes for this book and developed its arguments. It has been a tortuous process, which has gone through many evolutions, but I hope the combination of extensive theatrical experience with eclectic reading will make for a compelling read.

There are many reasons for the oubliette into which these characters have frequently been consigned. But if the claim for Shakespeares universality often seen as the ultimate expression of his worth is to be sustained, we should recognize that it cannot be found in the narrow experiences of one particular class. It is deeply un-Shakespearean to ignore his working men and women, let alone dismiss them as grotesques with little to say or do except make the audience laugh. Instead, as I will try to show, they are vividly drawn, three-dimensional figures, bursting with life and independence of mind, who make a vital contribution to the drama and its underlying purposes. That is certainly what I sensed in that cramped rehearsal room in Cambridge all those years ago.

It is time to test the validity of that youthful insight.

AUTHORS NOTE

All quotations from Shakespeare (except where otherwise indicated) are from The Complete Works, ed. Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor, John Jowett and William Montgomery (Oxford, 1986).

Shakespeares interest in working people is not matched by the English fine artists of the period. For this reason, the illustrations in Poor Naked Wretches are largely taken from Dutch or German sources. There is little to suggest that the clothes worn by this class were dramatically different across Northern Europe, and it is hoped that the quality of the illustrations compensates for any minor geographical or cultural discrepancies.

Albrecht Drer,