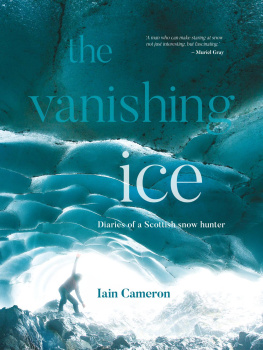

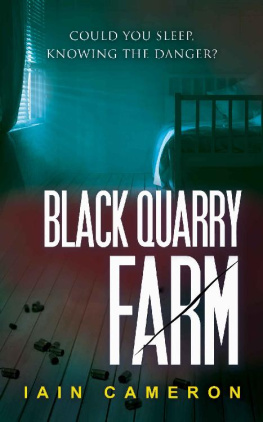

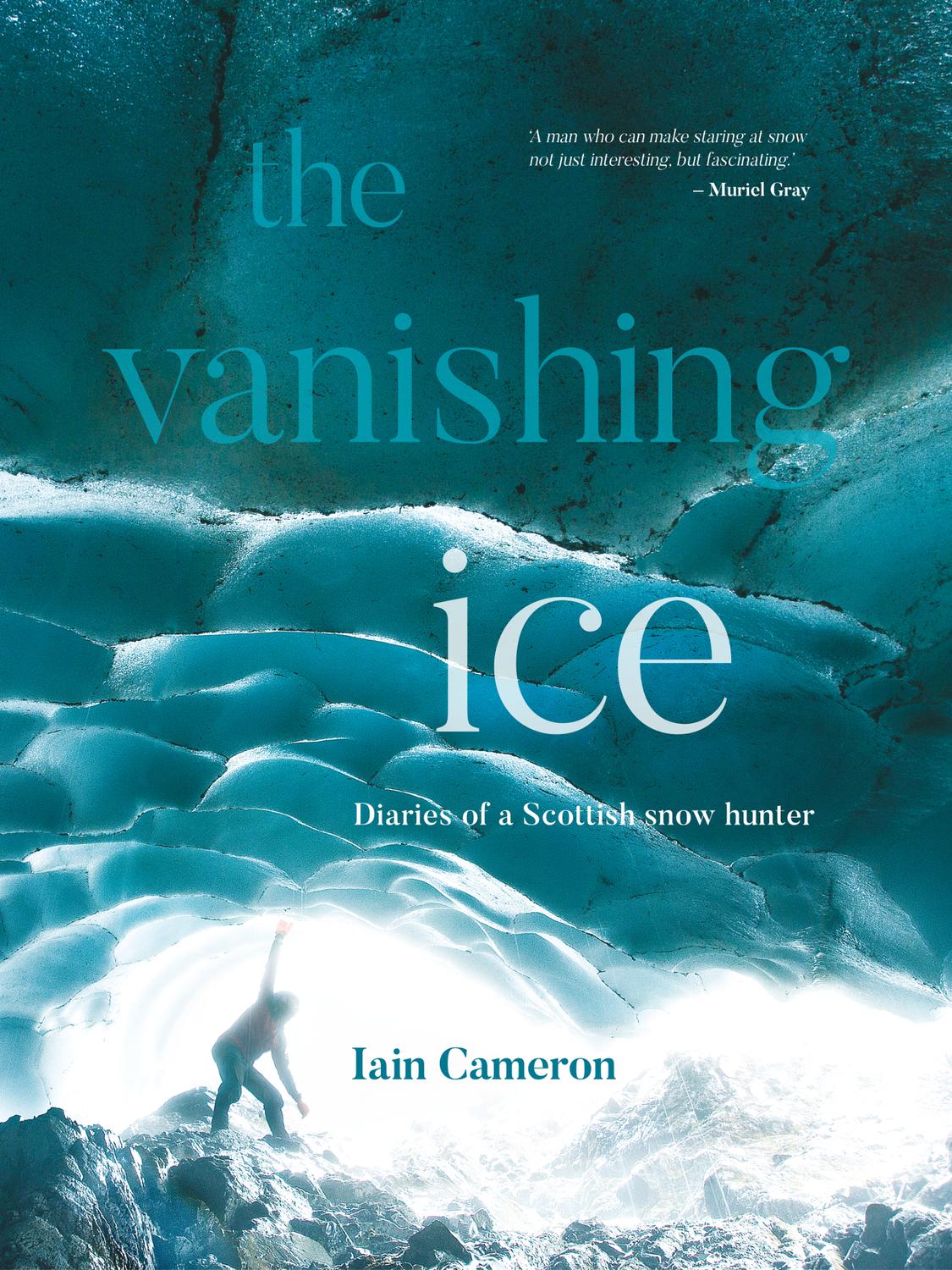

Early one morning in May 1983, nine-year-old Iain Cameron looked out of the living room window and glimpsed a shining patch of brilliant white on distant Ben Lomond. This sparked a fascination with snow patches that would become a lifes work. A citizen scientist, Iain has written more than twenty scientific papers for the Royal Meteorological Societys Weather journal; and he is the co-author of Cool Britannia (2010), a book examining the history of snow patches in Britain during the Little Ice Age. Iains work has been featured in the Guardian, the Independent and the Sunday Times, and he is a regular contributor to the Times and the BBC. He has appeared on Winterwatch and Countryfile and in numerous features on BBC Radio Scotland. He lives in Stirling and spends many weekends in the Scottish Highlands carrying out detailed fieldwork.

A man who can making staring at snow not just interesting, but fascinating.

Muriel Gray

Like some guardian of a lost folk memory, Iain Cameron wanders the Highlands in search of patches of snow that have held out stubbornly against the march of the seasons. Nestled in a remote gully, the last remnant of a forgotten ice age melts into a trickle and then is gone. His work is done for now, but the snows will return.

Nicholas Hellen, Sunday Times

Possibly the only writer who can pack history, geography, meteorology and adventure into tiny patches of snow.

Muriel Gray

THE VANISHING ICE

IAIN CAMERON

First published in 2021 by Vertebrate Publishing. This digital edition first published in 2021 by Vertebrate Publishing.

Vertebrate Publishing

Omega Court, 352 Cemetery Road, Sheffield S11 8FT, United Kingdom.

www.v-publishing.co.uk

Copyright Iain Cameron 2021.

Front cover: The snow cathedral of Ben Nevis, September 2016. Murdo MacLeod.

Author photo: The author partially hidden beneath a snowdrift on Ben Nevis in July 2016. Alistair Todd.

Other photography by Iain Cameron unless otherwise credited.

Iain Cameron has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

This book is a work of non-fiction. The author has stated to the publishers that, except in such minor respects not affecting the substantial accuracy of the work, the contents of the book are true.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781839811081 (Hardback)

ISBN: 9781839810886 (Ebook)

ISBN: 9781839810893 (Audiobook)

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanised, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher.

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologise for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

Cover design by Jane Beagley, Vertebrate Publishing. Production by Cameron Bonser, Vertebrate Publishing.

www.v-publishing.co.uk

To Adam.

Though no longer with us,

his presence is enduring and ubiquitous.

Contents

I emerged at last, breathless, on to the plateau. The ominous-looking wintry squall that had been chasing me up the hill arrived from the west just as I completed the last few heavy steps of a relentless climb from the col, some 1,200 feet below. As I stood upright once more and filled my lungs with the rarefied Lochaber air, the first outlying snowflakes of the squall danced down harmlessly enough. The initial flurry tends to do that: a few slivers corkscrew down from the sky and land softly on your sleeve or face, just on the leading edge of the gale that rides invariably behind them. But this is, literally, the calm before the storm. Ive been in this situation more times than I can remember, and I know whats coming next.

Overnight snow already lay thick on the plateau, and the forecast promised more for the rest of the day and the next. Taking a minute to orient my internal compass and restore my breathing to something resembling normality, I reached into the side of my rucksack for one of the bottles of flavoured water I carried, only to find that there was ice floating in it. As I tipped my head back to pour the freezing mixture into my mouth, the first wave of the storm hit me hard.

* * *

x The day had started three hours earlier in the deserted glen far below. A man I trusted a long-time snow observer had told me that there were two old patches left over from the previous winter in one of the high corries on this hill. This seemed unlikely to me, as the autumn weather had been mild warm, even. I needed to be sure, though. I had to count every last relic of snow from the preceding winter before they were buried for another nine months or so. Missing even one would have felt like failure. But there was a problem: I had never been to this corrie before. It lurked on the edge of my knowledge. An apparently tricky place to reach even in summer, it was going to be doubly so in winter conditions. But, since no one else had volunteered to venture into this neglected corner of the Highlands, I decided there was no alternative but to travel there myself.

The climb from the car park had started memorably, but not for the reasons one might hope. On the upward pull that eventually reaches on to the col, about twenty minutes after starting, I chanced across a dying red deer. He was a handsome old stag and lay about fifteen feet from the stalkers track. His front-right leg looked badly broken and, clearly, he could not move. His big brown eyes stared at me as I neared him, and he opened his mouth, attempting a roar to scare me off but managing only a hollow, thin rasp. It was a pitiful, tragic sight to see, and I could offer him no solace. I moved off, regretfully, hoping his death would come quickly and that this sad, chance encounter wouldnt amount to a macabre omen for my trip.

About an hour and a half later, I arrived at the foot of the col, where the first impediment presented itself. The overnight snow had been heavier than forecast and my path upwards on to the plateau was unfathomable beneath the fresh falls. All around me the landscape was winter, not autumn. The late-year, lifeless vegetation poked through the snow in an apparent attempt at defiance of its surroundings. Thick and ominous cloud swirled around the higher reaches of the hills to the west, whose summits were coated white.

xi In the absence of any discernible path, I could do nothing else but one thing: climb. So, picking out the least hazardous and most obvious-looking route, up I went. It was steep. Really steep. I gained height quickly as a result, though, and luckily the path became clearer. The snow that had fallen filled the hollows where thousands of boots had trodden, and it snaked up the escarpment at a more forgiving angle although to call it a path would have been generous. It was no better than an indistinct goat track, and goats would have thought twice about ascending it in these conditions. It became steeper the higher I got, and as I paused half-way up for breath, I turned around to see whence Id come. The hills that encircled me were splattered with thick snow, and any heather that didnt lie under the white blanket was a dull, lifeless mahogany brown. A dark line of approaching weather, the squall of snow, raced towards me. I reckoned I had fifteen minutes to reach the top before it caught me up and deposited its considerable payload.

![Iain Maitland [Iain Maitland] - Mr Todd’s Reckoning](/uploads/posts/book/141709/thumbs/iain-maitland-iain-maitland-mr-todd-s.jpg)

ii

ii