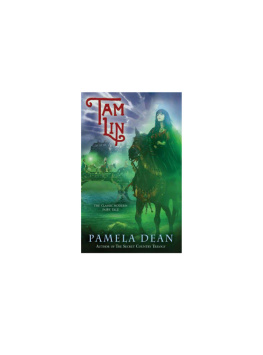

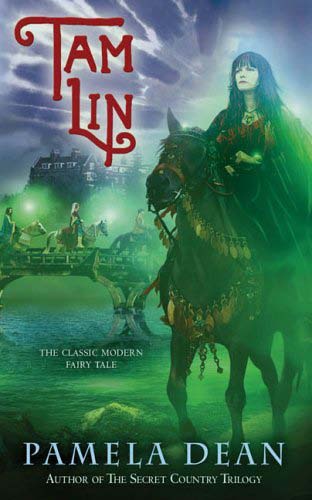

TAM L I N

Pamela Dean, P.J.F.

T H E F A I R Y T A L E S E R I E S

C R E A T E D B Y T E R R I W I N D L I N G

TOR

fantasy

A Tom Doherty Associates Book

NEW YORK

This book is for Terri Windling

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to quote from The Lady's Not forBurning by Christopher Fry 1950, 1976, 1977 by Christopher Fry. Published by Oxford University Press.

TAM LIN

Introduction copyright 1991 by Terri Windling, The Endicott Studio Copyright 1991 by Pamela Dyer-Bennet

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, Inc.

49 West 24th Street

New York, N. Y. 10010

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dean, Pamela

Tam Lin / Pamela Dean.

p. cm. (Fairy tale)

"A Tom Doherty Associates book."

ISBN 0-312-85137-5

1. Tam Lin (Legendary character)Fiction.

I.

Title.

II. Series.

PS3554.E1729T36

1991

813'.54dc20

90-49033

CIP

Printed in the United States of America

First edition: April 1991

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A C K N O W L E D G M E N T S

I am grateful to Patricia Wrede and Caroline Stevermer, and to Steven Brust, Emma Bull, Kara Dalkey, and Will Shetterly, for their ability to be both honest and encouraging; and to my husband, David Dyer-Bennet, kindest of project managers.

I N T R O D U C T I O N

F A I R Y T A L E S

There is no satisfactory equivalent to the German word mrchen, tales of magic and wonder such as those collected by the Brothers Grimm: Rapunzel, Hansel & Gretel,Rumpelstiltskin, The Six Swans, and other such familiar stories. We call them fairy tales, although none of the above stories actually contains a creature called a "fairy." They do contain those ingredients most familiar to us in fairy tales: magic and enchantment, spells and curses, witches and trolls, and protagonists who defeat overwhelming odds to triumph over evil. J. R R. Tolkien, in his classic essay, "On Fairy-Stories," offers the definition that these are not in particular tales about fairies or elves, but rather of the land of Faerie: "the Perilous Realm itself, and the air that blows in the country, I will not attempt to define that directly," he goes on, "for it cannot be done. Faerie cannot be caught in a net of words; for it is one of its qualities to be indescribable, though not imperceptible."

Fairy tales were originally created for an adult audience. The tales collected in the German countryside and set to paper by the Brothers Grimm (wherein a Queen orders her stepdaughter, Snow White, killed and her heart served "boiled and salted for my dinner,"

and a peasant girl must cut off her own feet lest the Red Shoes, of which she has been so vain, keep her dancing night and day until she dances herself to death) were published for an adult readership, popular, in the age of Goethe and Schiller, among the German Romantic poets. Charles Perrault's spare and moralistic tales (such as Little Red Riding Hood who, in the original Perrault telling, gets eaten by the wolf in the end for having the ill sense to talk to strangers in the wood) was written for the court of Louis XIV; Madame d'Aulnoy (author of The White Cat) and Madame Leprince de Beaumont (author of Beautyand the Beast) also wrote for the French aristocracy. In England, fairy stories and heroic legends were popularized through Malory's Arthur, Shakespeare's Puck and Ariel, Spenser's Faerie Queene.

With the Age of Enlightenment and the growing emphasis on rational and scientific modes of thought, along with the rise in fashion of novels of social realism in the nineteenth century, literary fantasy went out of vogue and those stories of magic, enchantment, heroic quests, and courtly romance that form a cultural heritage thousands of years old, dating back to the oldest written epics and further still to tales spoken around the hearth-fire, came to be seen as fit only for children, relegated to the nursery like, Professor Tolkien points out, "shabby or old fashioned furniture... primarily because the adults do not want it, and do not mind if it is misused."

And misused the stories have been, in some cases altered so greatly to make them suitable for Victorian children that the original tales were all but forgotten. Andrew Lang's

Tam Lin, printed in the colored Fairy Books series, tells the story of little Janet whose playmate is stolen away by the fairy folkignoring the original, darker tale of seduction and human sacrifice to the Lord of Hell, as the heroine, pregnant with Tam Lin's child, battles the Fairy Queen for her lover's life. Walt Disney's Sleeping Beauty bears only a little resemblance to Straparola's Sleeping Beauty of the Wood, published in Venice in the sixteenth century, in which the enchanted princess is impregnated as she sleeps, waking to find herself the mother of twins. The Little Golden Book version of the Arabian Nights resembles not at all the violent and sensual tales actually recounted by Scheherazade in

One Thousand and One Nights, shocking nineteenth-century Europe when fully translated by Sir Richard Burton. ("Not for the young and innocent..." said the Daily Mail.) The wealth of material from myth and folklore at the disposal of the story-teller (or modern fantasy novelist) has been described as a giant cauldron of soup into which each generation throws new bits of fancy and history, new imaginings, new ideas, to simmer along with the old. The story-teller is the cook who serves up the common ingredients in his or her own individual way, to suit the tastes of a new audience. Each generation has its cooks, its Hans Christian Andersen or Charles Perrault, spinning magical tales for those who will listeneven amid the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century or the technological revolution of our own. In the last century, George MacDonald, William Morris, Christina Rossetti, and Oscar Wilde, among others, turned their hands to fairy stories; at the turn of the century lavish fairy tale collections were produced, a showcase for the art of Arthur Rackham, Edmund Dulac, Kai Nielsen, the Robinson Brotherspublished as children's books, yet often found gracing adult salons.

In the early part of the twentieth century Lord Dunsany, G. K. Chesterton, C. S.

Lewis, T. H. White, J. R. R. Tolkiento name but a fewcreated classic tales of fantasy; while more recently we've seen the growing popularity of books published under the category title "Adult Fantasy"as well as works published in the literary mainstream that could easily go under that heading: John Barth's Chimera, John Gardner's Grendel, Joyce Carol Oates' Bellefleur, Sylvia Townsend Warner's Kingdoms of Elfin, Mark Halprin's AWinter's Tale, and the works of South American writers such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Miguel Angel Asturias.

It is not surprising that modern readers or writers should occasionally turn to fairy tales. The fantasy story or novel differs from novels of social realism in that it is free to portray the world in bright, primary colors, a dream-world half remembered from the stories of childhood when all the world was bright and strange, a fiction unembarrassed to tackle the large themes of Good and Evil, Honor and Betrayal, Love and Hate. Susan Cooper, who won the Newbery Medal for her fantasy novel

Next page