Contents

The different types of curator

(subject specialist, collection-based, independent, artist, head of department)

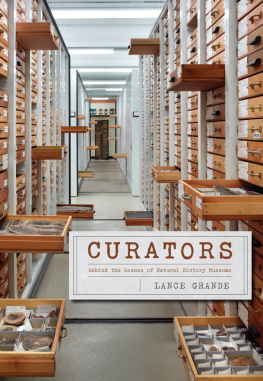

Introduction

What is a curator?

Our contemporary definition of a curator is more broad-ranging than ever before. A curator is probably best known as the selector and interpreter of works of art for an exhibition; however, the role now incorporates those of producer, commissioner, exhibition planner, educator, manager and organizer. In addition, the curator is now likely to be the person responsible for writing wall labels, catalogue essays and other supporting content for the exhibition (increasingly this includes web texts and social media). The 21st-century curator may also be expected to interact with the press and the public, giving interviews and talks. Curators may be required to participate in fundraising or development activities such as sponsors or patrons events, and they may be involved in the academic world through partnerships with schools, colleges or universities, providing lectures, seminars, internships or work placement opportunities. As the curatorial profession is continually changing, developing and expanding, so the curators range of skills must develop and expand to meet these new challenges and opportunities.

The word curator first came into use as meaning overseer, manager or guardian in the mid-14th century. The root of the word is in the Latin verb curare meaning to take care of; originally it was used to describe those who were in charge of minors or lunatics. The nascent development of the role of curator in its current form is inexorably linked to the development of collecting as a pastime of the rich.

Collecting objects of diverse forms including natural and geological specimens, as well as carvings, decorative objects and art has a long cultural history, but has roots in the 17th century, when the very wealthy would set aside rooms in their homes to store and display their collections. These rooms were known as Cabinets of Curiosities (or by the German terms Kunstkammer art room and Wunderkammer wonder room). Those who were responsible for looking after works of art, collections of objects or antiquities became known as Keepers (for obvious reasons) a term that continues in use today in some European museums and sometimes refers to a senior curatorial position, or a curatorial role that has more responsibility, including additional research, writing and connoisseurship.

The history of criticism is much better known [than the history of curating] there aren't books about this parallel activity of creating exhibitions. Maybe it has to do with the fact that the curator wasnt, and maybe shouldnt be, such a well-defined figure.

Daniel Birnbaum,

Director, 53rd Venice Biennale

The philosopher Robert Hooke (16351703) was the first Keeper of the Repository of The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. The Royal Society, as it is now known, was established in 1660 to promote knowledge of the natural world through observation and experiment; the Repository was a public collection of natural and artificial objects, some common and some rare. In 1661 Hooke is referenced in the Societys archives as the Curator of Experiments. However, this job title did not refer to works of art or objects at all; instead it was Hookes responsibility to organize, care for and coordinate the weekly demonstrations of new scientific experiments. Hookes role expanded into one we now understand as keeper over the forty years he held the post. He catalogued, researched and recorded (with others) much of the work done by the Society. Viewed in combination, Hookes two roles bear direct comparison with our contemporary interpretation of a curators role.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries large collections were formed across the developed world, many later bequeathed to the nation. During this period the roles of museum director, keeper and curator were often blurred and interwoven, but it is the term curator that came to be most closely associated with the custodian of a museum or other collection of objects art or otherwise. The curators role today can be equally broad and all-encompassing. It may include making decisions on what is added to a collection (acquisition by purchase, commission or gift); producing original and in-depth research into an object or collection of objects; the care and documentation of the works; and the sharing of knowledge with the public and / or peers through scholarly publications and exhibitions.

The curators core role is often seen as that of an expert with regard to visual culture and taste. This archetype began to take shape around the mid- to late 19th century and crystallized in the middle of the 20th. The role of the museum itself changed during this period too. The museum was no longer simply a repository for a collection it instead came to be seen as a place of engagement and learning, where artists and curators could work together to experiment with new means of expression and presentation. It was also at this moment that a number of influential art-world figures began to appear and to present exhibition projects that did more than simply display works from a collection. This new breed of curator made connections between diverse works, chose to focus on an artistic or historical theme, or brought together groups of artists who were working in a similar way.

Ground-breaking projects were produced by luminary postwar curators such as Pontus Hultn and Harald Szeemann. As Director of Stockholms Moderna Museet (1958 73), Hultn pioneered the inclusion of talks, debates, concerts and film programmes within the gallery, as well as presenting major art movements such as American Pop for the first time in Europe. Moving to Paris in 1973 he established the Muse national dart moderne (Centre Georges Pompidou), where he continued to produce seminal exhibitions that sought to link the cultural production of European capital cities and marked a paradigm shift in exhibition making. Harald Szeemann began his career as an actor, stage designer and painter and didnt start making exhibitions until 1957. Curator of the Kunsthalle Bern from 1961 to 1969, he gave artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude the first opportunity to wrap an entire building. In 1969 he presented the exhibition Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form that established a great exhibition format, in which works of art were linked to a central concept and brought together in new and sometimes challenging relationships. To some extent it was this type of exhibition-making that first led to criticism of curatorship it being suggested that the balance of focus between art, artist and curator was weighted too much towards the curatorial concept.

Throughout the 1990s there was a greater focus on the history of curatorial practice, certainly in English-speaking countries, but it is still nevertheless quite a sparse history. One of the most influential contemporary curators, Swiss-born Hans Ulrich Obrist (who is Co-Director, Exhibitions and Programmes and Director of International Projects at the Serpentine Gallery, London) has stated that for him the reason why I do it [i.e. document the history of curating] is actually not in order to historicize things, but to understand why these things are not known.

What is clear is that, whether taking on the more traditional role, or its contemporary revision, curators play a vital and essential part in our understanding of the art and culture of both past and current times. Curators, working in a symbiotic relationship with artists, challenge perceptions and investigate what future culture may be and what it might look like.

Next page