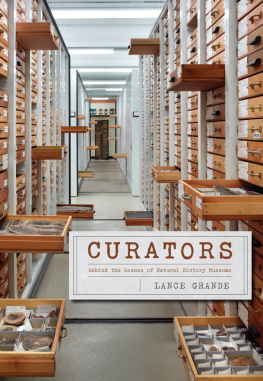

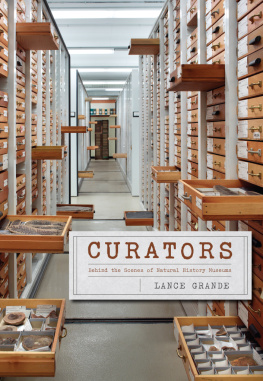

Curators

Behind the Scenes of Natural History Museums

Lance Grande

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by Lance Grande

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017.

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-19275-8 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-38943-1 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226389431.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Grande, Lance, author.

Title: Curators: behind the scenes of natural history museums / Lance Grande.

Description: Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016032596| ISBN 9780226192758 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226389431 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Grande, Lance. | Natural history museum curatorsIllinoisChicagoBiography. | Field Museum of Natural HistoryBiography. | BiologistsIllinoisChicagoBiography. | PaleontologistsIllinoisChicagoBiography. | Natural history museum curators. | Curatorship. | Natural history museums.

Classification: LCC QH31 .G67 2017 | DDC 508.092 [B]dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016032596

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Dianne,

for your sweet love and support.

To Lauren, Elizabeth, Patrick, and Kevin,

that you each follow your own ambitions

with joy and conviction.

Fulfillment is more about the journey

than the destination.

Contents

Curators of Natural History and Human Culture

I am a curator: one of the primary research scientists at the Field Museum in Chicago. Ive been a curator for more than thirty-three years. I was inspired by curators before me who were influenced by curators before them.

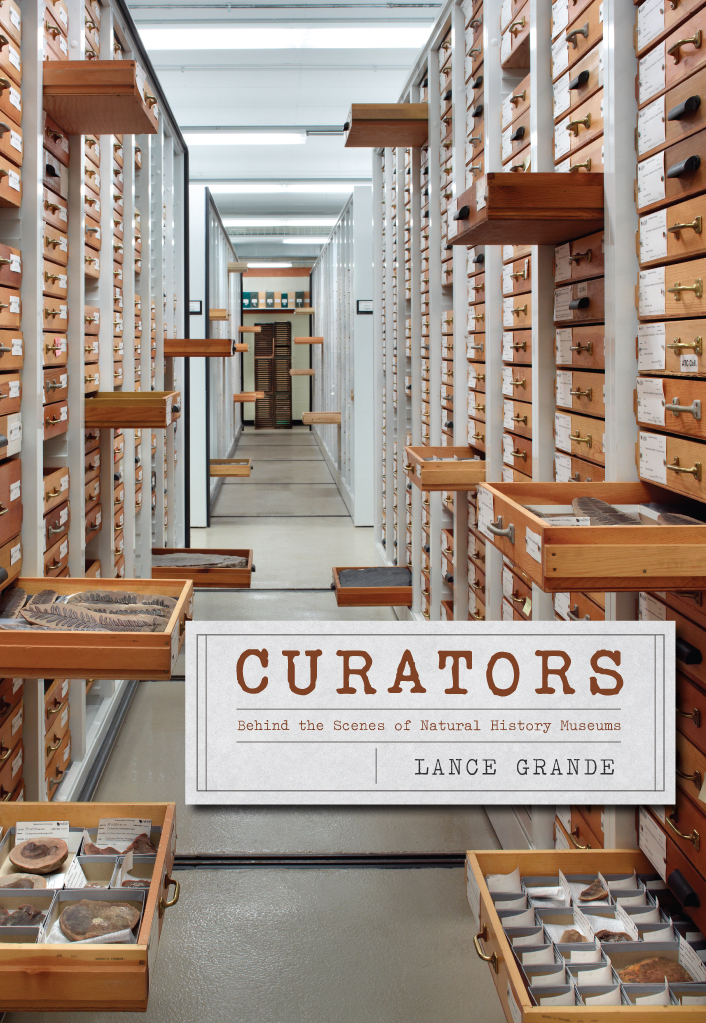

The Field Museum is one of the largest natural history museums in the world. It houses more than 27 million specimens ranging from DNA to dinosaurs. For more than 120 years, curators have assembled this collection to study and document our planets biology, geology, and human culture. Their research has provided unique insight into the history and diversity of our world. While leading the Research and Collection division of the museum for more than eight years as a senior vice president, I came to realize that few people understood what a natural history museum curator does. That realization was the first impetus for me to write this book.

In major natural history museums of North America, the term curator is used for the research scientist whose job is to bring authority and originality to their museums scientific message. They explore the natural and cultural world through field expeditions; they do original research based on objects of natural or cultural history (specimens and artifacts); they disseminate knowledge of original scientific discoveries to students, other scientists, and the general public. Curators are passionate about their quest for understanding the Earth and its people. They challenge convention, sometimes even at their own peril, to enable scientific progress.

The origins of curators and museums of cultural and natural history began long ago. The earliest known cultural history museum was established over 2,500 years ago by a Babylonian princess and her father in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Ur (now the Dhi Qar Governorate of Iraq). Princess Ennigaldi was a high priestess of the moon god Nanna, and the daughter of Nabonidus, last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Nabonidus collected antiquities and is the earliest known archaeologist. In 530 BC he influenced his daughter to develop a museum focusing on the cultural history of Mesopotamia. She became the museums first curator and developed a research program around its collection of artifacts. This was centuries before the study of natural history was established, and her study of culture was primitive by todays standards. All advances in science must be considered within the context of their own time, and the idea of a research facility with an archived collection was a huge step for the sixth century BC .

Ennigaldis museum was active until around 500 BC when the city of Ur was abandoned due to deteriorating environmental conditions (prolonged drought and changing river conditions). There are no records of what happened to the princess. The museum was lost for thousands of years until it was rediscovered in 1925 by the famous archaeologist Leonard Woolley. While excavating an ancient Babylonian palace, Woolley discovered a large chamber with a curious collection of neatly arranged artifacts ranging in age from 2100 BC to 600 BC . The objects were associated with a series of inscribed clay cylinders representing labels. Woolley soon realized that he had discovered the remains of the worlds oldest known museum.

The earliest known center for natural history research goes back about 2,300 years, to the third century BC . The Lyceum, in classical Athens, was a center of scholarly research and learning where Aristotle developed one of the earliest hierarchical classifications of living things. He proposed a Scala naturae (Great Chain of Being, also called Ladder of Life) to classify plants and animals according to their structure. This classification, while not as sophisticated or as comprehensive as the later classification of Carolus Linnaeus, was one of the first to use the internal structures of organisms. Today Aristotle is considered to be the founder of comparative anatomy and the first genuine natural history scientist. He pioneered the study of zoology and made significant contributions to the studies of geology, botany, physics, and philosophy. Aristotles work was ahead of its time, and he eventually angered high religious officials, who denounced him in 322 BC for not holding the gods in honor. He fled Athens, fearing for his life, and died later that year of natural causes. Although Aristotles research was specimen-based, he left no surviving collection of museum specimens. In fact, we have little record of natural history collections made until the sixteenth century.

Through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, natural history collections were generally personal accumulations of specimens and artifacts organized by people who made the bulk of their income as physicians, professors, or advisors to royalty or religious authorities. These collections were often associated with small museums that amounted to little more than what were called cabinets of curiosities (the word cabinet referring to a room rather than a piece of furniture). These displays of eclectic and poorly organized objects were precursors to modern-day natural history museums. The collections sometimes blended fact and fiction, featuring faked mythical creatures (e.g., unicorns, mermaids, dragons, and gryphons) made from parts of real animals stuck together by barber surgeons. (At that time, surgery was the charge of barbers rather than physicians.) The purpose of a cabinet of curiosities was not scientific as we understand science today. Instead, these crude exhibits were meant to be theaters of wonder, propaganda, or even displays of personal wealth and power. Although many of the objects were authentic pieces of nature and antiquity, few of them ever made their way into modern museum collections.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).