A Gathering of Wonders

ALSO BY JOSEPH WALLACE

The American Museum of Natural Historys

Book of Dinosaurs and Other Ancient Creatures

The Audubon Pocket Guide to Dinosaurs

The Deep Sea

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaur

A Gathering

of Wonders

BEHIND THE SCENES AT

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM

OF NATURAL HISTORY

Josepn Wallace

A GATHERING OF WONDERS: BEHIND THE SCENES AT THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY. Copyright 2000 by Joseph Wallace. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wallace, Joseph E.

A gathering of wonders : behind the scenes at the American Museum of Natural History / Joseph Wallace.1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-312-25221-8 ISBN 978-0-312-25221-2

1. American Museum of Natural History. 2. Natural history.

I. American Museum of Natural History. II. Title.

QH70.U62 N489 2000

508'.074747'1dc21 00-025481

Book design by Michelle McMillian

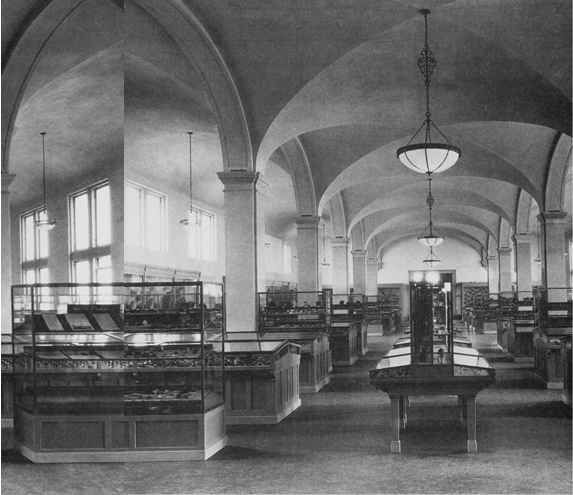

Frontispiece photo: The Morgan Gem and Mineral Hall in the 1890s.

First Edition: June 2000

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Nora, Gerrie, and Liz,

better friends than theyve

known these past few years.

Contents

Foreword

My grandfather, John T. Nichols, was for many years the Curator of fishes at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. One of his sons, my father, David G. Nichols, often worked on small mammal collections for the Museum. My mother, Monique Robert Le Braz, met my father at the Museum thanks to the kindly actions of her uncle through marriage, Trubee Davison, who was once president of the Museum. While in that position, Trubee obtained for my mother a minor research post in anthropology, and thats when she met my dad.

Since I owe my existence to this felicitous confluence of personalities in that great institution, you can see how the Museum would loom rather large in my legend.

When I was a child in the 1940s I got to runkle around in the estuaries and backwaters of the Museum. My grandfather had a messy but fascinating office located somewhere in the musty bowels of the hallowed edifice. I remember a bunch of yellowed publications heaped about in a general state of disarray, and shelves of bottled frogs and fishes. I myself became a devotee of formaldehyde, and went through a stage during my grammar school days where just about anything that slithered or flapped or croaked or burbled was fair game for my poisonous little vats or for my collecting jars half-filled with naphthalene crystals.

My father set his traps in fields around the old family homestead in Mastic, New York, on the South Shore of Long Island. Manys the time I followed after him carrying my own little pouch, while he harvested the catch from the night before. Then I sat at the kitchen table studiously observing as he skinned the mice and shrews and other elfin bodies, preparing them as Museum specimens. I also attended the old man when he plucked small brown bats from behind the green shutters of the family house, bats that he also sent to the Happy Myotis Hunting Grounds in the name of science. On other occasions, when Pop had a permit to collect grosbeaks, solitary sandpipers, or red-eyed vireos, I tagged along to watch him blast them from tree tops or sand dunes with a .410 shotgun: He rarely missed.

During this same epoch, my grandfather, John T. Nichols, was an inveterate collector of box turtles at the Mastic estate. No, he neither pickled them in formaldehyde nor dropped them into pots of soup, but rather marked their shells with numbers and dates and recorded their existence in notebooks. Often we found turtles that had been caught and released decades earlier, and this provided quite a thrill.

The whole point of these exercises was to become familiar with the natural world, and thus to venerate it. I swallowed that theme song hook, line, and sinker, and have been an amateur naturalist ever since, unequivocally enamored of just about everything that lives, eats, propagates, and defecates around the globe, except, perhaps, for humanity, which on occasion can sorely try my patience.

When I reached the age of fifty-one, and my grandfather had been dead for thirty-three years, I gave a talk at the Museum for the seventy-fifth anniversary gathering of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, an organization founded by Grandpa in 1913. After the speech, a friend in the audience took me back into the clandestine innards of the institution to a dank and cavernous room with hundreds of shelves housing bottles of weird preserved fishes. We went up and down the aisles, looking for creatures that my grandad had bagged, and I must say we found a fair number: That was exciting. We even took a few over to some sinks and drainbords and had a closer look. Many of the critters that John T. gathered for posterity were fairly bizarre: They had threatening teeth and bulging eyes. I was impressed.

Unfortunately, thats the last time I was able to visit the Museum, a moment already nine years in the past. Unfortunately also, is the fact that my father died two years ago, in April 1998. With his passing I lost an intimate connection to eighty-one years of knowledge of, and great curiosity about, life on earth. Thats a connection I will keenly miss.

Whenever I visited Pop during the last years of his life in Smithville, Texas, we drove around looking for caracaras, discussing Houston toads, or remarking on the great blue herons at Beuscher Lake, a body of water that he checked in on daily. From his childhood until the end, my father regarded the natural world from a perspective of awe and obligation. We talked about the past, his early days as a naturalist, and the future of the planet. He was discouraged about all the human-made perturbations of ocean, coral reef, and rain-forest canopy, yet ever hopeful that people might one day get it together before the species self-destructs.

In 1935 my father had a spider named after him: Xysticus nicholsi. This creature appeared on his neck one buggy afternoon while he was bogged down in a swamp in Alaska. Dad popped it in a bottle, and sent the bottle to the New York Museum for identification. I suspect that spider is still located somewhere in the Museum, on a shelf gathering dust. One day I must fly to the Big Apple and try to find it. Ill have to hurry, though, because Ive got a bum heart and my longevity is problematic. Mind you, Im not complaining; we all wind up as dust.

What is wonderful about the American Museum of Natural History is that it speaks to eternity. So much life is there, captured as it were in a bottle; life from millions of years ago... life that is touted in current headlines... life that may still be percolating a billion years hence. Anyone who ever walks through the doors to gape at a whale or a dinosaur or at a diorama of Pleistocene shenanigans, cant help but be enriched by the experience. The American Museum of Natural History is one of the seminal and most energetic museums on earth, and my point (at last!) is that the book in your hands certainly proves it.

Next page