STUFFED ANIMALS & PICKLED HEADS

STUFFED ANIMALS & PICKLED HEADS

THE CULTURE AND EVOLUTION OF NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUMS

STEPHEN T. ASMA

Oxford New York

Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires

Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul

Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai

Nairobi So Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto

Copyright 2001 by Stephen T. Asma

First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001

First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2003

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Asma, Stephen T.

Stuffed animals and pickled heads : the culture and evolution of natural history museums/

by Stephen T. Asma.

p. cm.

Includeds bibliographical references (p.).

ISBN 0-19-513050-2 (cloth) ISBN 0-19-516336-2 (pbk.)

1. Natural history museumsHistory.

2. Natural historyExhibitionsDesignsHistory.

1. Title

QH70.A1.A75 2001

508.074dc 00-040674

Book design by Adam B. Bohannon

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

For my brothers, Dave and Dan

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

Flesh-eating Beetles and the Secret Art of Taxidermy

CHAPTER 2

Peter the Greats Mysterious Jars: How to Pickle a Human Head

and Other Great Achievements of the Scientific Revolution

CHAPTER 3

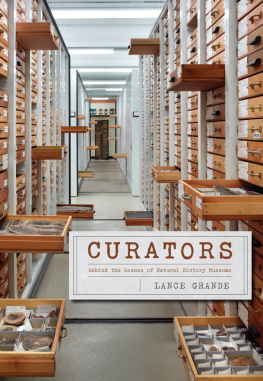

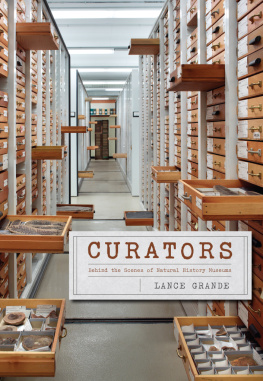

Taxonomic Intoxication, Part I: Visualizing the Invisible

CHAPTER 4

Taxonomic Intoxication, Part II: In Search of the Engine Room

CHAPTER 5

Exhibiting Evolution: Diversity, Order, and the Construction of Nature

CHAPTER 6

Evolution and the Roulette Wheel: A Chance Cosmos Rattles Some Bones

CHAPTER 7

Drama in Diorama: The Confederation of Art and Science

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am happy to acknowledge the generous support that many people provided throughout this project. Many museum curators, librarians, and staff people helped me in my research, and I am particularly indebted to Eric Gyllenhaal, John Bates, Doug Dewitt, Tara Hess, Nina Cummings, Shelly Ericksen, Simon Chaplin, Frdric Guilbert, and John Wagner. I wish to express my gratitude to Christian Trokey, whose professionalism, skill, and good humor helped to secure the image permissions. Thanks also to Arthur Naiman, Peter Olson, Mary Kay Brennan, Audrey Niffenegger, Richard Ross, Allah from Milwaukee, Kathryn Koch, Jim Christopulos, Peking Turtle, Tom Greif, Baheej Kaleif, Les Van Marter, Sue Warga, Columbia Colleges Faculty Development Grant, the Lake Geneva Campus of George Williams College, and my students, who continue to teach me many important lessons.

My agent, Sheryl Fullerton, believed in this project from the start, and her careful attention to the manuscript and the editorial phase improved the book immeasurably. My excellent editor at Oxford University Press, Kirk Jensen, patiently guided the manuscript from its histrionic infancy to its current form. Of course, I take full responsibility for the books remaining flaws. Stephen Jay Gould offered encouragement and advice at the outset. Thanks also to Michael Ruse, John Greene, Michael Ghiselin, and especially Phillip R. Sloan, who shed significant light on Cuviers and Hunters respective collections. I wish to express my appreciation for the ongoing support from Genie Gatens-Robinson and John S. Haller, and the very pleasant Building Bridges: Religion and Science conference at Southern Illinois University.

Other authors will understand me when I say that, in addition to the exhilaration involved, writing a book is a thoroughly manic and solitary experience. If not for my family, this project would have had me in the rubber room many times. So, my deepest gratitude to Ed, Carol, Dave, Dan, Elaine, Lynn, G-man, Maddy, all the Wagreich and Sherman clans, and, most important, Heidi, whose encouragement and support made much more than this book possible. When my anxieties were escalating unchecked, Heidi assured me that if I died in a freak accident, she would make sure that the manuscript was indeed published, but, alas, she would not honor my request to be preserved as a stuffed taxidermy mount.

INTRODUCTION

Toward the center of Londons small Hunterian Museum stands an enormous human skeleton labeled the Irish Giant. The giant skeleton was once the frame of Mr. Charles OBrien, born in Ireland in 1761. OBrien came to London in 1782 and exhibited himself, charging half a crown, as the tallest man in the world at 8 feet 2 inches. The towering man seems to have suffered from acromegaly, a pathological enlargement of the body that results from an overactive pituitary gland.

John Hunter, the famous British anatomist, met the Irish Giant in London and openly vowed to have the Giants skeleton for his scientific collection. By 1783 OBrien was on his deathbed, and, apparently thinking he should be less exhibitionist in death than in life and fearful that his skeleton would indeed end up in Hunters collection, he paid some fishermen to ferry his soon-to-be-dead body out to sea and weight it down with lead. But Hunter, somehow informed of this development, intervened at the last minute and successfully bribed the ersatz undertakers. He brought OBriens corpse to his Earls Court home, where he prepared the specimen himself by boiling it in a huge kettle.

Two centuries later I stood gawking in amazement at OBriens colossal skeleton. Compared to Hunters nightmarish pathology cabinets to the left, the skeleton actually seemed quite tame. Contemplating these ghastly but fascinating exhibits, I felt as though I was learning more than scientific information. I was glimpsing the workings of John Hunters mind, the mind of a man who seemed simultaneously a genius and a madman. Its no wonder that science has been saddled with Frankenstein stereotypes. Imagine living down the lane from John Hunter, where on any given day you might see him chasing his mutant roosters around the yard, or feeding his bright red pig, or ushering into his barn some shady grave diggers carrying mysterious bulky sacks.

Next page