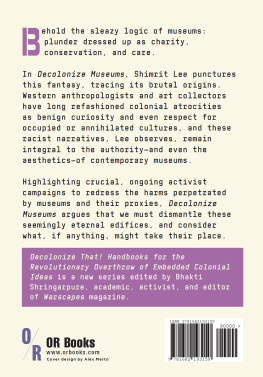

The Decolonize That! series is produced by OR Books in collaboration with Warscapes magazine.

2022 Shimrit Lee

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

All rights information:

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

First printing 2022

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Lapiz Digital Services. Printed by BookMobile, USA, and CPI, UK.

paperback ISBN 978-1-68219-315-0 ebook ISBN 978-1-68219-316-7

Forthcoming from Decolonize That! Handbooks for the Revolutionary Overthrow of Embedded Colonial Ideas

Edited by Bhakti Shringarpure

Decolonize Self-Care by Alyson K. Spurgas and Zo Meleo-Erwin

Decolonize Multiculturalism by Anthony C. Alessandrini

Decolonize Drag by Kareem Khubchandani

CONTENTS

EDITORS PREFACE

Back in 2008, I was at a Super Bowl party where I met some young veterans who had returned from fighting in the 2003 Iraq war. I was regaled with all kinds of stories, and I tried my best to hum and haw and stay clear of unleashing my views about American imperialism or the nations addiction to perpetual war. But one story finally put me over the edge. One of them figured out I was a cultured type who liked art and books, and bragged to me about the day the Iraq Museum in Baghdad was destroyed. It was chaos, he said, everyone was grabbing whatever they could, and he couldnt resist making off with a trident. He even managed to bring it back home to Oklahoma where it proudly hung in his basement. Above the TV. But why, how could you, its not yours it all fell on deaf years. Dont get upset, the Iraqis didnt care about it, he assured me. They dont care about such stuff. Violent desecration of cultural heritage served with a side of racist mansplaining. Why was I surprised? It was Super Bowl Sunday, after all.

Looting, theft, war and imperialism are not simply side effects but the foundation upon which museums are constructed. I write this in May 2021 as bombs rain down on Gaza, and Israel has ramped up a barbaric campaign of ethnic cleansing in occupied Palestine. Footage of babies being pulled out of the rubble and buildings crumpling up in a heap airs in real time before our eyes on social media, and a letter titled Free Palestine/Strike MoMA: A Call to Action is making the rounds. The letter implicates several Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) trustees with funding and reinforcing projects of settler-colonialism and racial capitalism not just in Palestine but worldwide. These words are particularly sharp and timely: Given these entanglements, we must understand the museum for what it is: not only a multi-purpose economic asset for billionaires, but also an expanded ideological battlefield through which those who fund apartheid and profit from war polish their reputations and normalize their violence. This makes clear that these violent histories are not a thing of the past but the very mode through which massive public institutions like museums sustain, grow and thrive.

Many of us instinctively feel discomfort around museums; we notice that in the dioramas of primitive peoples, the figures are usually dark skinned; that the huge pillars from the Persian city of Susa displayed in Paris Louvre, or those taken from the Temple of Dendur exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum must have cost a fortune to bring over from those countries, why were they allowed, and how did they even do it; that theres a diversity problem in the art world and massive, high-profile art exhibits tend to showcase white artists, some of whom make balloon animals; that exhibit openings in stark white spaces are fancy and exclusive. In fact, such events will make you fuss about your look, your accent, your address, your wallet size. If youre not white, wealthy, posh, well-traveled or cultured, are you meant to be on the other side of the glass? The question echoes in that oft-regurgitated comment from visitors to the messy and cluttered museum in Cairo: they, the Egyptians, cannot be trusted to be custodians of their own heritage. You can apply this comment liberally to other places: Burkina Faso, Benin, India, Congo, Indonesia and coincidentally, this exercise will also vomit up an old colonial map of Europes old glory days.

Behold the sleazy logic of museums: first comes the plunder, and the plunder is then dressed up as charity, conservation and care.

In Girl, Woman, Other, Booker Prize-winning author Bernadine Evaristo has a portrait of a Black woman called LaTisha Jones, a high school dropout who grew up in grim council housing in London. Now a mother of three living paycheck to paycheck, LaTisha recalls that her parents took her to all the free museums in London. Mummy said children who did well in life had parents who took them to museums. No distinction is made between a natural history museum or a science museum or an art museum. Its just museums, any museum will do.

What strikes a melancholic chord in the passage is the intuition that museums can give you cultural capital: that imperceptible je ne sais quoi , that scent of social class you cant shed. This also explains the recent trend in reclaiming museum spaces within Black popular culture. We saw Beyonc and Jay-Z rent out the Louvre to film their music video Apeshit. Despite the feeble critiques of their centering of capitalist excess, the sheer pompous buying out of the museum is not only an excellent fuck-you to the institutional white supremacy that the Louvre represents but also a gesture of ownership over a space that continues to be uncomfortable for non-white people from a range of social classes. The French series Lupin also played with these significations. In the show, protagonist Assane Diop (played by Omar Sy) is a Black Frenchman son of an immigrant father exploited, framed and killed by traditionally wealthy, art-collecting, art-dealing, and trafficking white employers. In order to avenge his father, he plots an exquisite jewelry heist. Diop plays with the museum staffs perceptions of a Black nouveau riche class and makes off with a historic diamond necklace right under their noses, disguised as a reclusive tech billionaire yet unknown to a woke white French society. Pop culture, more and more, is routinely exposing this intuition about class, race and museum culture, and Shimrit Lees Decolonize Museums also uses such references to shine a light on these core connections.

Whether its through references to Indiana Joness exciting looting exploits in Raiders of the Lost Ark or the subversive heist by Black Panthers Eric Killmonger, Shimrits book reminds us that the ties that bind museums, theft, knowledge production, and resource-hoarding have never really been hidden, but somehow they have been idealized. We continue to revere museums and refuse these truths. We choose instead to believe in the reformation of such institutions that pretend to be offering a public education and upholding patriotic national agendas through cultural conquest. We think diverse curators and diverse artists and asking disenfranchised communities will do the trick. But the violence that undergirds museums is not a vague colonial violence of cultural memory, or an erasure of heritage. It is a specifically settler colonial violence that is ongoing and underway. Museums are an extraordinary force of gentrification. First comes the museum, then the high-rise buildings, then the sushi and brunch spots, then the yoga studios you get the drift. Along the way, dispossessed populations get brutally uprooted and shoved out into peripheries.

Next page