Contents

Page List

Guide

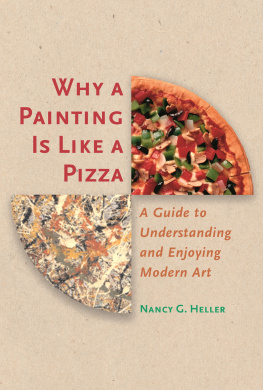

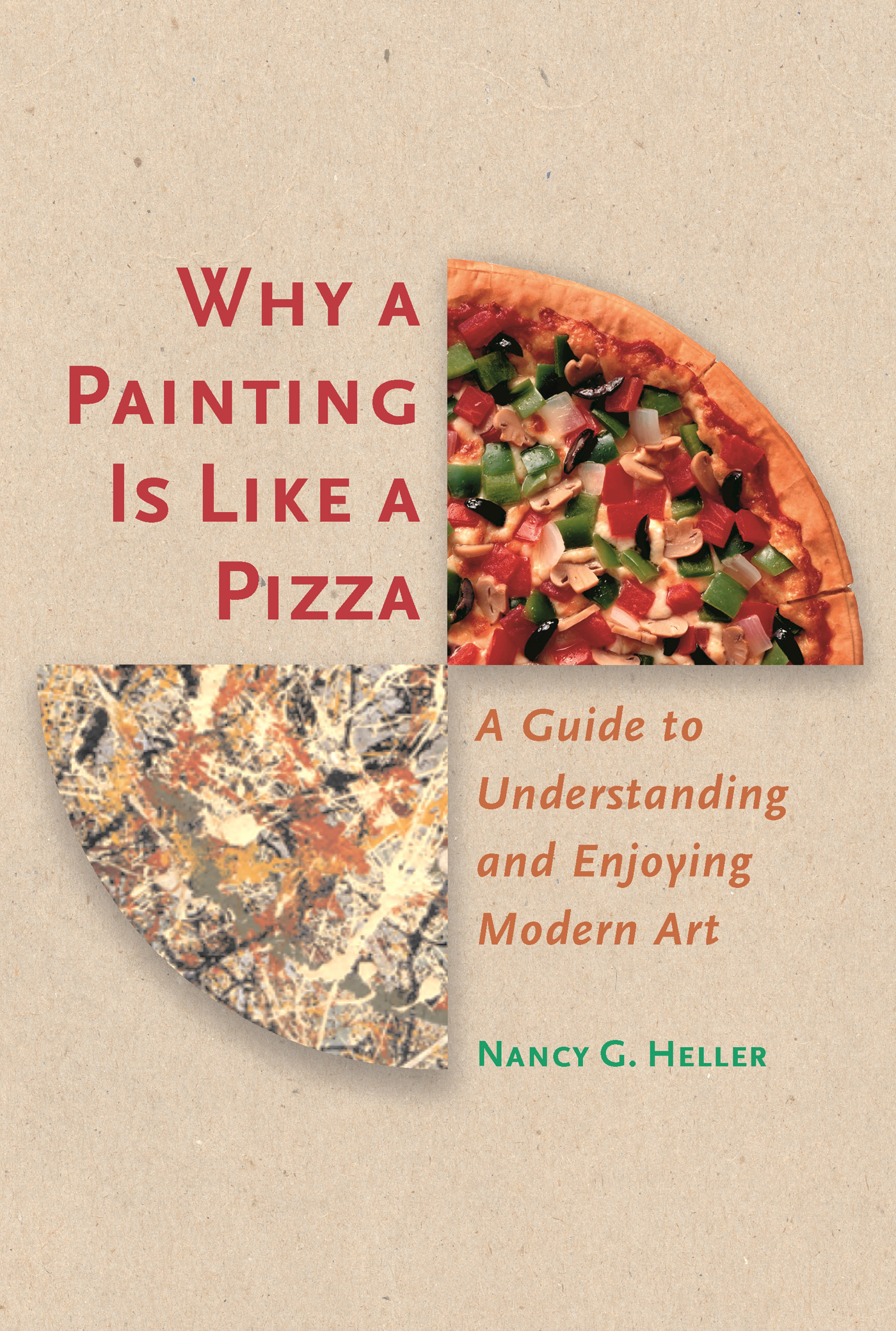

WHY A PAINTING Is LIKE A PIZZA

WHY A PAINTING Is LIKE A PIZZA

A Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Modern Art

NANCY G. HELLER

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

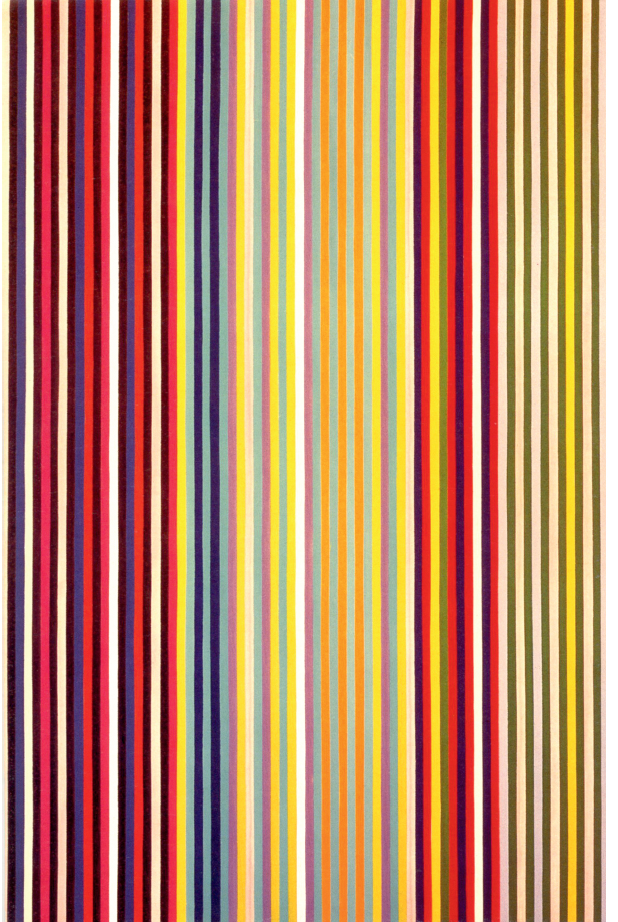

FRONT COVER: (UPPER RIGHT) Pizza with vegetable toppings (detail); (LOWER LEFT) Jackson Pollock, Number 3, 7949: Tiger (detail), 1949. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Gift of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, 1972. 2002 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photographer: Lee Stalsworth FRONTISPIECE: Gene Davis, Moondog, 1965. Detail of

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

www.pupress.princeton.edu

Copyright 2002 Nancy G. Heller. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publishers, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Designed by Patricia Fabricant

Composed by Tina Thompson

Printed by South China Printing

Manufactured in China

(Cloth) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

(Paper) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Heller, Nancy G.

Why a painting is like a pizza : a guide to understanding and enjoying modern art / Nancy G. Heller.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-09051-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0-691-09052-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Art, Modern20th century. 2. ArtAppreciation.

I. Title.

N6490 .H42 2002

759.06dc21

2002022725

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A S THE CHILD OF A PROFESSIONAL ARTIST, I grew up surrounded by a wide variety of original paintings, sculptures, and printssome made by my father, and others by his artist friends. For years I assumed that this was normal since, for my family, artincluding abstract and otherwise unconventional artwasnt some esoteric mystery; it was my fathers job. Therefore, our private collection seemed no more remarkable than the stationery someone elses father sold for a living, and considerably less exciting than the chocolates stockpiled by a schoolmate whose dad worked for a candy company. As I grew older, though, I discovered that few other families displayed original art in their homes and that abstract art, in particular, was something most people only encountered, grudgingly, on field trips from school. As a result, after earning my doctorate in modern art history, I decided that I wanted to lobby on behalf of all types of nontraditional art.

During the last twenty years I have concentrated on the problems of understanding modern art, presenting public lectures (for Elderhostel, the Smithsonian Institutions Resident Associates Program, and the Pennsylvania Humanities Council) and writing articles for popular newspapers and magazines. In so doing, I try to convince other adults that they need not feel intimidated by such arteven if they dislike it. People tend to resist, or at least feel uncomfortable around, ideas and objects that are unfamiliar. But visual art is such an important part of contemporary culture that many people with no background in the arts still feel compelled to understand it. Therefore, Ive written this user-friendly guide, whicheven though it obviously cannot substitute for studying art seriously, whether in an academic setting or independentlycan give interested readers a simple, straightforward way of looking at, and thinking about, modern art in general and abstract art in particular.

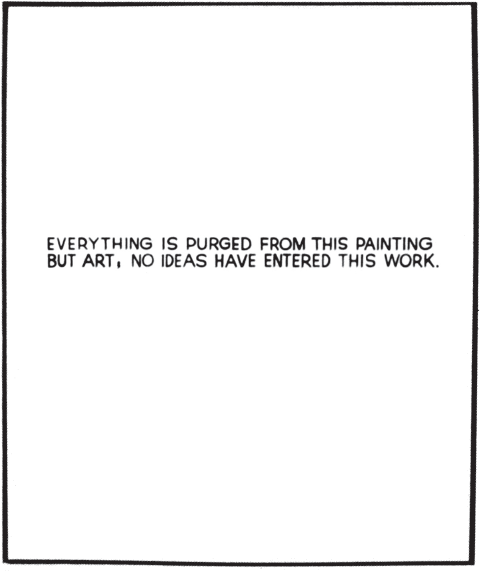

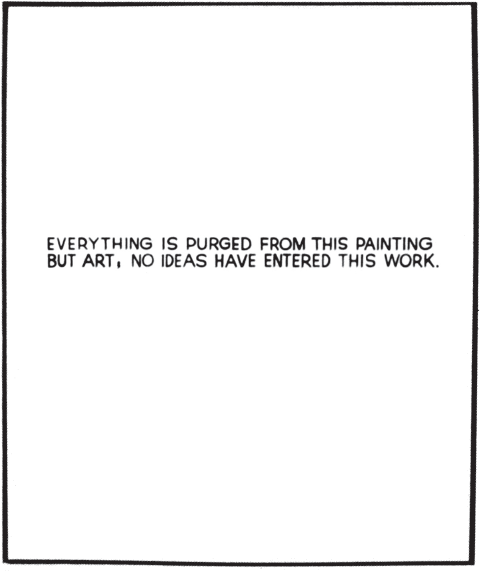

1. John Baldessari (American, born 1931), Everything Is Purged from This Painting but Art; No Ideas Have Entered This Work, 196668. Acrylic on canvas, 68 56 in. (172.7 142.2 cm). Courtesy of the artist

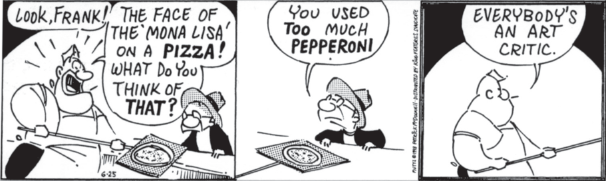

2. Patrick McDonnell, Mutts, 1998

INTRODUCTION

We must remember that art is art. Still, on the other hand, water is waterand east is east and west is west, and if you take cranberries and stew them like apple sauce, they taste much more like prunes than rhubarb does.

Groucho Marx, in Animal Crackers, 1930

A PAINTING REALLY IS LIKE A PIZZA, in a surprising number of ways. This is something I realized, at the ripe old age of twenty-eight, when I cooked my first pizza from scratch. At the time I was teaching art history in a small east Texas town, where only one local restaurant served pizza. Since the tomato pies sold by that establishment bore little resemblance to the pizzas Id known and loved in New Jersey, I took the radical step of consulting a recipe, purchasing ingredients, and concocting my own customized pizza. The results were decidedly mixed, but the taste was superior to anything then available outside Dallas. More important, the process of making my own pizza led to an epiphanywhich in turn determined the title of this book.

A detailed, point-by-point comparison of a particular painting with a specific pizza will be provided at the beginning of . Right now, though, I would like to point out two critical ways in which these apparently dissimilar items are related. Both paintings and pizzas depend on visual balance for much of their overall impact, and though each can be judged by a set of generally accepted standards, ultimately the viewer/consumer must evaluate each painting and pizza in terms of her own personal taste.

That first Texas pizza reinforced for me the basic principles of two-dimensional design. It was easy enough to fashion the proper shape by using a round pizza pan, but it proved much harder than I had expected to create a pleasing surface pattern with the toppings I had chosen. To understand the importance of such compositional balance, think how you would feel if the restaurant where you had ordered a pepperoni-and-mushroom pizza with green peppers and black olives presented you with a pie that had all the pepperoni slices crowded onto one edge. It would be far more satisfying to look at, and eat, a pizza that had all four toppings spread out evenly across the crust. Paintings achieve a comparable sense of visual balance by a variety of means, but the end result is the same: a canvas that feels right when you look at it.

That others grasp what I have in mind seems unessential, at least as long as they have something else in theirs.

Alexander Calder, 1951

The importance of personal taste seems obvious when dealing with a pizza. Anyone whos ever worked in an Italian restaurant knows that people order their pizzas in all sorts of ways: with a thin or a thick crust, lightly browned or well done; with tomato sauce, white sauce, or some other more exotic variant; and topped with anything from pineapple wedges to shrimp, artichoke hearts, or escargots. Only the most arrogant foodie would maintain that just one of these is the true pizza. Individual attitudes toward paintings are just as variedand just as valid. Yet otherwise reasonable people often feel free to dismiss whole groups of paintings and sculptures that they dislike, or that make them uncomfortable, even declaring that they are not art at all. My position is that anything anyone says is art should in fact be regarded as art. Rather than asking, Is X art? I prefer to ask, Is X a kind of art that I find interesting? If not, I wont spend much time looking at or thinking about X. But it is pointless to deny that it is art simply because I dont like it or because it challenges traditionally accepted ideas about what art is supposed to be. The marvelous thing about art is that it is a vast, amorphous, ever-expanding category, one for which great thinkers have struggled over the ages to provide a precise definition. Moreover, as we will see in , even the most established definitions of art have been frequently challenged over the past century.