Contents

Guide

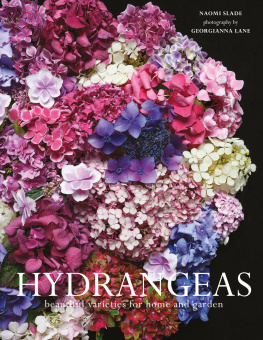

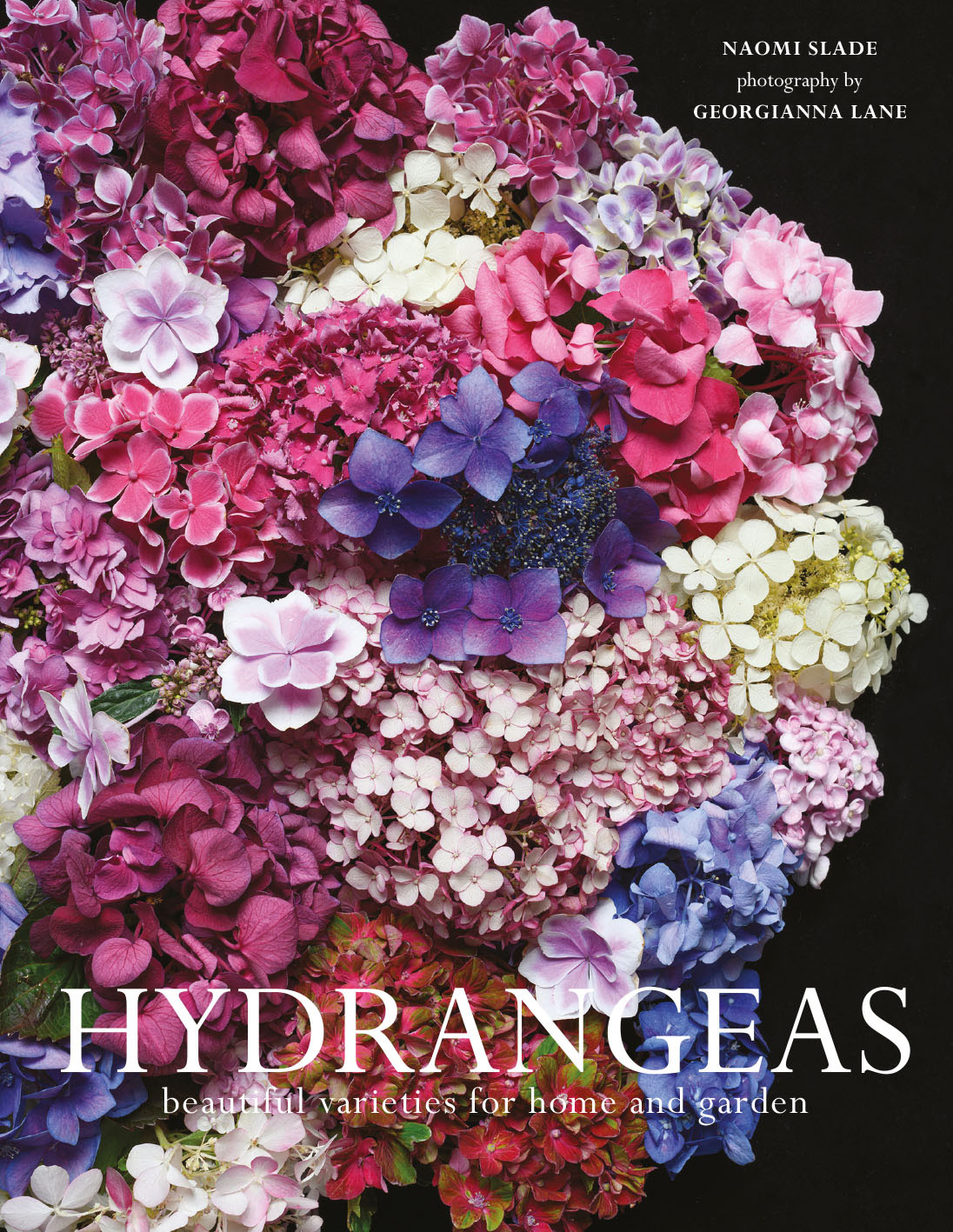

HYDRANGEAS

HYDRANGEAS

beautiful varieties for home and garden

NAOMI SLADE

photography by

GEORGIANNA LANE

Contents

INTRODUCTION

A FLOWER OF A THOUSAND FACETS, THE HYDRANGEA NEVER CEASES TO SURPRISE AND ASTONISH. THEY ARE CHAMELEONS AND SHAPE-SHIFTERS, MORPHING FROM FRESH AND VIBRANT YOUTH TO LANGUID AND MYSTERIOUS AGE WITH NO DISCERNIBLE LOSS OF CHARM OR INTEREST. AND WHILE THIS PLANT MAY NOT HAVE ALWAYS BEEN UNIVERSALLY LOVED, IT CARES NOT ONE IOTA. THE HYDRANGEA IS HERE TO STAY; WITH US ALWAYS AND FAMILIAR CERTAINLY, YET STILL IMBUED WITH GREATNESS.

Fashion is a capricious thing and hydrangeas, more than many plants, have had their low points as well as their triumphs. Discovered but not applauded, passed over in the annals of botanical significance, given away as an also-ran by those who might have cherished them. Yet hydrangeas have slowly surged, gradually building a reputation and a following; not catapulted to glory as a manufactured pop phenomenon, but gaining recognition the old way, through hard graft and reliability, like the band that plays working mens clubs and back-street dives, building up and burning slowly to finally become a national treasure.

Throughout their history, hydrangeas have tended to divide people. Some think they are marvellous in almost every way; others consider them an abomination. Even the tastemakers disagree. American magazine and television mogul Martha Stewart loves them; pop legend Madonna reputedly loathes them. And, until relatively recently, I would have been with Madonna all the way.

When I first met hydrangeas, they were bulky, dated landscape shrubs. They grew in a row under the window in my grandmothers coastal garden, the flowers vast lumpen mops of dull pink and mauve that my granddad called Queen Mothers Hats. My grandmothers nickname was Queenie and the reference to the majestic headgear must have amused her no end.

Hydrangeas were simply not to my taste. My young self preferred dainty wild flowers, fragrant herbs and the juicy charms of the fruit cage. Yet it is unfair to judge an entire genus on a couple of neglected specimens viewed with an uncompromisingly critical pre-teen eye. Especially when said genus is going through a renaissance, a pop-star-style reinvention of the type where a dated crooner teams up with a hot young act and suddenly reveals that they can bust out the tunes in a whole new way, capturing hearts and exploding in popularity as they do so.

But youth is fickle and critical. It has a first taste of olives and they are the most revolting thing in the world; a glass of cheap plonk leads to a hotly declared dislike of red wine. There is, as yet, no appreciation of uniqueness, quality and subtlety, whether that be the olives from Manzanilla, Kalamata and Morocco fruity, salty or tart or the endless complexities of grape, climate and soil that go into crafting a fine wine.

So it is with hydrangeas. Reflection and experience, an appreciation of new developments and the simple turning of the world has made them not just freshly relevant but ultimately desirable. They are now courted, coveted and cooed over, wherever they can be grown or shipped to.

While the bulky old faithfuls still exist, they are a renewed force in a landscape or woodland garden design. And they are now joined by newer, more compact plants; plants that are ideal for containers. Breeders have developed fresh lacecaps, airy as a bridal veil, and elegant, sophisticated panicles in cream and green. They offer the exquisite excitement of a flower that ages not just gracefully, but magnificently, with antique shades of verdigris, teal and damson, before finally fading to a spare but deliciously delicate skeleton in the garden.

The versatility of hydrangeas must, in part, have contributed to their renaissance. They are perfect as a container specimen and house plant, and are suited to floristry of all kinds. In the garden, they are design magic. Hydrangeas as grand shrubs that flex their landscape muscle and compete with trees for impact; hydrangeas as modest-yet-handsome additions to a mixed border; those varieties whose large and lavish blooms thrust them into the spotlight as spectacular specimen plants; and those bred for neatness and good behaviour, a gift to urban gardens and small spaces.

The consumer has become increasingly sophisticated, too, and there is a greater recognition that plump, bosomy mopheads are not the only option. The understated delicacy and variety of lacecap flowers, so much in the Japanese tradition, appeal to gardeners that prefer their plants to be more violin concerto than big band.

In the West, hydrangeas crept on to the gardening scene in the eighteenth century, some brought in from North America and others collected from the plethora of species to be found in Asian countries such as Japan, Korea and China. Wild and free, the Hydrangea macrophylla types grow comfortably in warmer maritime environments, while sundry hardier species extend into the mountains.

Here are remote populations of hydrangeas that have not made it into cultivation and may never do so. Yet, among them, are plants with horticulturally tempting qualities such as a towering arboreal form or a tendency to re-bloom. Such plants still evoke the tingle of excitement that must have been felt by the first explorers and collectors ever to penetrate these forbidden areas.

The Victorians, who were never backwards in coming forwards when attributing significance and whimsy, took a somewhat unflattering point of view when it came to hydrangeas, and seemed oddly unaware of the ironies of sending flowers to insult the receiver. A bunch of hydrangeas on your doorstep apparently implied that the sender thought you were a braggart (not that any popinjay worth their salt would care). A rejected suitor with wounded amour propre and an axe to grind might, similarly, send hydrangeas as a floral slap and accusation of frigidity which would probably only help to cement the givers position as well and truly dumped.

In Asia, the relationship with hydrangeas is comparatively dignified yet ceremonial, and regionally quite complex. In Japan, at least, the hydrangea carries less horticultural significance than it does cultural significance. Other countries, meanwhile, seem relatively indifferent, although there is a flourishing market for the cut flowers in Hong Kong and Singapore. Across the board, the picture that emerges is as might be expected, as regards something that is a relatively common native flower, rather than an exotic garden specimen.