Contents

Guide

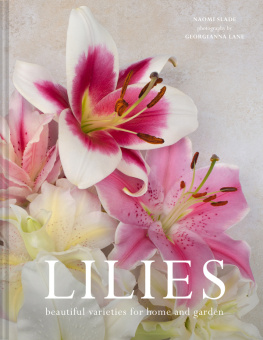

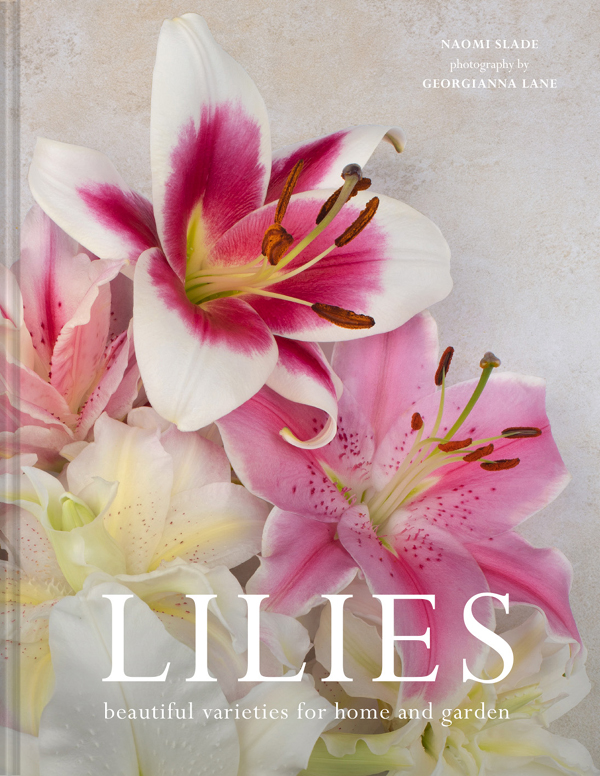

LILIES

LILIES

beautiful varieties for home and garden

NAOMI SLADE

photography by

GEORGIANNA LANE

Contents

INTRODUCTION

ALMOST IMPOSSIBLY EVOCATIVE, THE LILY IS A FLOWER WITH A THOUSAND TALES TO TELL. IT IS A SYMBOL OF SEX AND PASSION, OF GODDESSES AND VIRGINS. A SIGN OF ABUNDANCE AND PURITY IN THE HANDS OF A BRIDE, IT CAN ALSO BE TORRID, DIVISIVE AND CAPRICIOUS. IT DELIGHTS IN COMPLEXITY AND FREQUENTLY MANAGES TO BE SEVERAL THINGS AT ONCE, YET ITS FABULOUS FRAGRANCE AND SYBARITIC GOOD LOOKS HAVE RENDERED IT ICONIC ACROSS THE GLOBE.

Lilies are familiar because they are ancient. Evolving before the very dawn of mankind, they were poised at our own birth to catch, embrace and captivate us. Despite the innocent blooms that dance in the wilderness, they tend to be portentous rather than frivolous, and they are never cosy. Adopted by religion, death and politics, the lily is a plant of ritual significance and multifaceted symbolism.

Yet they are undeniably beautiful and, more than that, they are useful in myriad ways. As the prairie harvest of the Native Americans and a dinner-table staple in China; employed in an ointment for footsore Roman soldiers and medieval cures for baldness; included in bouquets and in funeral wreaths for that perfume, so coquettish and seductive, that also masks so well the stench of death.

The early history of mankind is inscribed in pictures. Art, sculpture and other forms of graphic representation frequently outlast fragile texts, and the earliest images of lilies are Minoan, relics of a civilization that flourished between 3000 and 1100 BCE. We know they are lilies; we can see them. But when it comes to the written word, the story starts to come unstuck.

In his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says: Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin (Matthew 6:28). Here, Jesus encapsulates the flower as a beautiful, relatable symbol of faith why, after all, should we concern ourselves with raiment and sustenance when all of nature is in the hands of a merciful God?

Although delivered by Gods own public speaker, this is an evocative metaphor by any measure; after all, we know lilies, do we not? Their beauty, their elegance, their simplicity and their perfume?

But presume to consider them properly, interrogate them, even, and it soon becomes evident that lilies represent something very complex indeed. The plant itself, its relationship with mankind throughout history, its social and religious significance, and even its horticulture are not quite the image of simplicity that is implied in this Biblical quote.

Even if taken literally, the passage could refer to almost any flower endemic to that region. The lily as an all-encompassing shorthand for the flowers, or even the beasts, of the field. A charming allegory in a sermon without footnotes.

As gardeners we also do our best to confuse ourselves, and a number of plants are recognized as lilies water lilies, Guernsey lilies, trout lilies, calla lilies, plantain lilies, lilies of the valley. Meanwhile, within the Family Liliaceae, are foxtail lilies (Eremurus) and pagoda lilies (Erythronium), as well as fritillaries and tulips. Yet, here too, we must cast these false lilies aside: this book concerns true lilies, the genus Lilium.

The very first lilies arose in a place in East Asia, around 19.5 million years ago; a point when primitive African primates were not yet apes and early hominids were just a faint twinkle in the eye of evolution.

Aeons passed and mountains rose; continents were torn apart and new ones created. In geological time the world is far from static, and as tectonic collisions built the Himalayas, the mountains profoundly impacted global weather systems, particularly monsoon patterns and periods of glaciation.

The proto-lily, minding its own business in a quiet corner of Asia, found its whole landscape rippling imperceptibly upwards. Plants that had evolved relatively close to sea level were suddenly thrust into the sky. Divided from their fellows by new mountains, glaciers and oceans, populations split into different lineages and diverged into various species in response to the changing landscape and climate.

With the Anthropocene, the ascent of lilies could be charted via art and cultural tradition. The Cretan walls entombed in volcanic ash, the petrified Ancient Egyptian perfumiers, the Assyrian bas-reliefs and the Roman funerary engravings appearing, over millennia, from Persia to the Far East. In the West, meanwhile, the hagiographic iteration and reiteration of the symbolic lily would verge on the tedious if the art in question was not all so very beautiful.

White lilies shook off the taint of Roman and pagan associations to become the icons of Easter and representations of the Madonna, springing miraculously from the tears of Eve or Christ. The Annunciation was a rich source of inspiration during the Renaissance, with occasional, spinechilling asides where Christ is seen nailed to a cross made of lilies, and the Pre-Raphaelite artists continued the theme. Rossettis depiction of Mary as a cowering teenager receiving lilies from the Archangel Gabriel in Ecce Ancilla Domini!, and John Singer Sargents famous Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, are delivered with the customary vivid sensuality of the age.

Notwithstanding the many woodcuts and illustrations in florilegia, herbals and botanical texts through the ages, the Dutch Masters painted their lilies in absorbing detail and the flower was a popular motif in Victorian and Arts and Crafts wallpaper.

The poetry of lilies is usually sensuous or mournful when it is not self-indulgent or excessive. Regrettably frequently, the quality of the tribute does not match its peerless subject. But exceptions include the work of Tennyson, Marvell and Keats, and the lily, almost inevitably, became the signature flower of that notoriously flamboyant rhymer and rake, Oscar Wilde.

What is intriguing, though, is the degree to which people see what they want to see embracing purity and ignoring perversion; acknowledging the light without the dark. Those who cheerfully quote the Song of Solomon (2:1): I am the rose of Sharon, and the lily of the valleys, unaccountably overlook the frankly erotic phrases that appear later in the text, concerning lips like lilies, dropping sweet-smelling myrrh (5:13) and references to breasts like young deer feeding among the lilies.