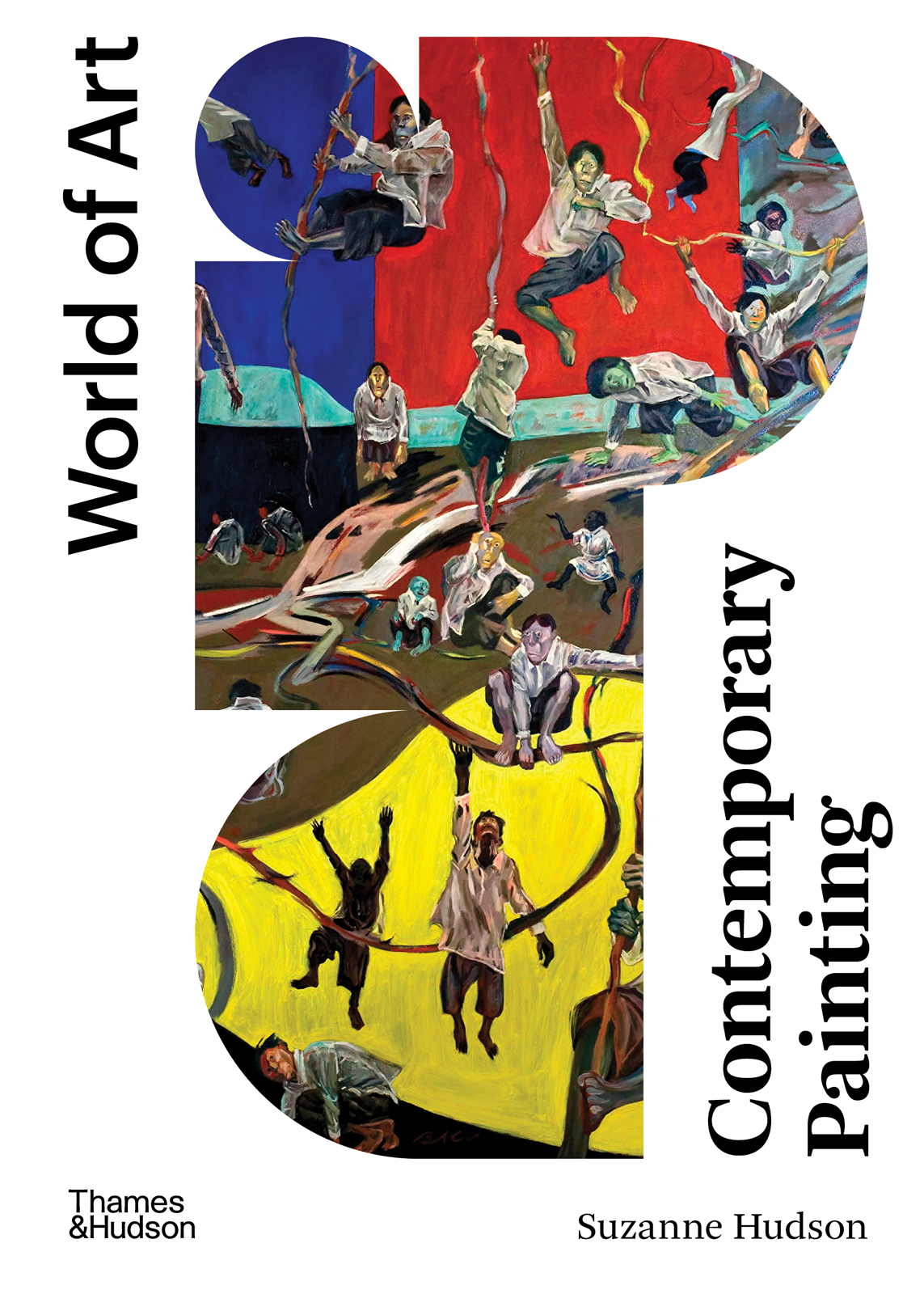

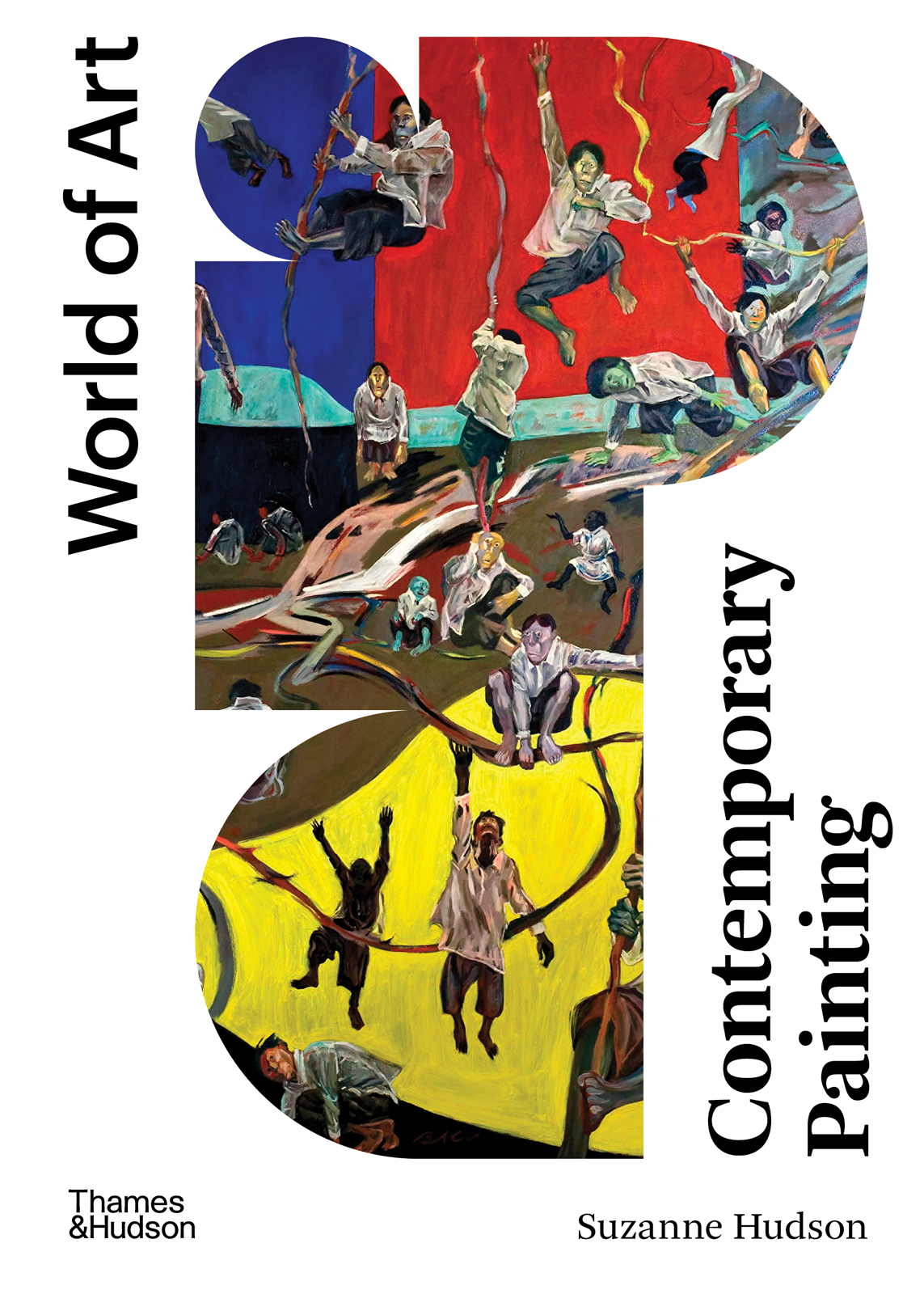

Yue Minjun, Inside and Outside the Stage, 2009

About the Author:

Suzanne Hudson is Associate Professor of Art History and Fine Arts at the University of Southern California. She is an esteemed art historian and critic who writes on modern and contemporary art, with an emphasis on painting, art pedagogy and American philosophy. She received her PhD from Princeton University.

Hudsons previous books include Robert Ryman: Used Paint, Agnes Martin: Night Sea and Mary Weatherford, and she is the co-editor of Contemporary Art: 1989 to the Present. She is a regular contributor to Artforum.

Contents

This is a book about contemporary painting from the first two decades of the 21st century. The term contemporary refers to art created in the present day and the recent past; it also specifies a historical period that comes after modernisms extension into postmodernism. Departing from the more ubiquitous sense that art is inevitably contemporary when it is made, this latter usage is characterized by pluralism and a global purview.

As contemporary painting remains consequential in our time, we might ask: how does it form, circulate and carry meaning? How does it relate to contemporary art more broadly, to its expanded geography and demographics? And to technology and media? Developing provisional responses to these and to related questions motivated me to write this book, which treats painting not as an isolated entity, but rather as a medium productively entangled in the world outside of its proverbial frame. Among so many other possibilities, a painting now may be outsourced to a village in Guangdong province, China, or it can be designed on-screen and printed on pre-primed linen using a commercial machine. A painting might hang on a wall, slight as a coloured shoestring or monumental as a space-filling mural, but it could also be used as a prop in a performance or serve as the backdrop for other actions, at times involving an audience that participates in realizing the work.

For many centuries, painting was an exemplary humanist object and the most prized form of Western art, but it needs to be addressed straight away that some readers might well question the fundamental premise of the book in assuming paintings continued relevance under changing circumstances. It has been contested in the digital age (and perhaps we should also ask what this tells us about our contemporary culture), though not for the first time. Indeed, the historical primacy of oil on canvas was reviewed with the arrival of photography in the 19th century: why labour over a painting when a camera could deliver an image with even greater verisimilitude? In the following century, it was opposed more directly by the readymade (the found object nominated as art by virtue of an artist asserting it as such, transforming it categorically, if not actually, as though with a magic wand).

Marcel Duchamps use of the readymade in the 20th century coincided with a decisive abandonment of painting, or in his words, retinal art. In fact, the smell of turpentine that Duchamp detested did not prove so easy to leave behind. A great many artists persevered with painting, and, in the years after World War II, again the medium flourished. Debates about the primacy and even feasibility of painting picked up in the 1960s, with pop arts extensive use of commercial imagery. Artists engaged techniques used in photographic reproduction, as well as mechanical means of production, challenging traditional methods of painting and the once sacrosanct boundaries between media. Later in that decade, text-based practices (often photographic), performance and other ephemeral actions gained prominence.

Where modernism came to be embodied by abstract painting that shunned external references, subsequent approaches expanded the idea of what an artwork could be, encompassing not just images and words but also that which surrounds them: architecture, the institution itself, the passage of time and peoples lives. This intersectionality came to be known as postmodernism. The new priorities seemed to disqualify painting, which was allegedly outdated and static by comparison, and was perceived as being divorced from conceptual currency and activist engagement.

Such considerations came to a head in the 1980s, with the triumphant return of painting. Partly in reaction to the liberation politics that characterized the preceding decades, a recuperative universalism renewed focus on ideas with presumed common applicability. This was the perfect storm for the ascendancy of neo-expressionism, wildly gestural painting that materialized human touch on the surface and supposedly communicated deep emotions. For supporters, it evidenced a transhistorical humanism that connected the entirety of creativity in paint, from works in caves to those displayed in the white cube. This convinced many that the recent topical avoidance of painting had been an insignificant blip in a longer, corrective course.

At the same time, certain eminent artists, writers and curators described the collapse of modernist painting and advent of postmodern art using the language of endgame. This is a term borrowed from chess, referring to the last stages of a game. In art, endgame was used to describe the theory that as modernist painting collapsed and postmodernism a heterogeneous set of practices united in their scepticism regarding collective truths, idealism and moral authority took root, painting could not be furthered. Instead, it would potentially endlessly re-examine ideas that had come before. This was not a critique of the practicability of the whole of painting, just its production under modernist circumstances.

In this context, the death of painting became glib shorthand for debates about the meaning of art in general and painting in particular in a free-market culture. Unable to achieve the weightiness that it once attained, painting lived on, but in light of identity politics and war, economic crises and clashes between generations it was seen as complicit in conservatism, retrograde in means and ends. Abstraction was panned for lacking content, and figuration for wallowing in canned sentimentality. Either way, it was seen as anachronistic, delivering value only as trifling decor, or so the argument went.

Of course, most critical stances on modernist painting were underwritten by historicism: a relativist, as opposed to universalist, approach to art history, which considers the significance of historical or geographical circumstance in the development of art. This was used to justify the timeliness of a reappraisal of medium. In this light, the endgame argument of the 1980s might be regarded as part of this same story, since it also involved re-evaluating the logic that had sustained the art practices being called into question. The idea of genres of art or even art as such coming to an end point is not unprecedented. Pliny, a Roman polymath who attempted a consolidated account of art in his Natural History (1st century CE), recorded that Greek art had stopped for more than a hundred years because the era was characterized by Hellenistic Baroque art that he did not much care for. A parallel to neo-expressionism resonates here.

Next page