Contents

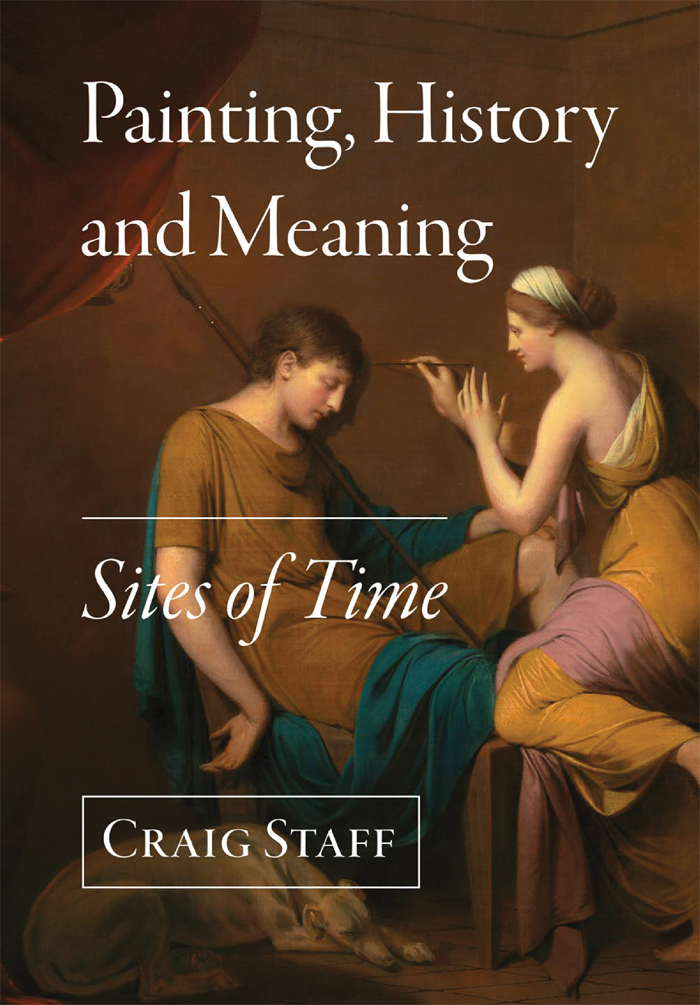

Painting, History and Meaning

Painting, History

and

Meaning

Sites of Time

Craig Staff

First published in the UK in 2021 by

Intellect, The Mill, Parnall Road, Fishponds, Bristol, BS16 3JG, UK

First published in the USA in 2021 by

Intellect, The University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th Street,

Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Copyright 2021 Intellect Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copy editor: MPS Limited

Cover designer: Aleksandra Szumlas

Production manager: Helen Gannon

Typesetter: MPS Limited

Print ISBN 978-1-78938-288-4

ePDF ISBN 978-1-78938-331-7

ePUB ISBN 978-1-78938-330-0

Printed and bound by TJ Books

To find out about all our publications, please visit our website.

There you can subscribe to our e-newsletter, browse or download our current catalogue, and buy any titles that are in print.

www.intellectbooks.com

This is a peer-reviewed publication.

In memory of Judith Ann Nosworthy

19312020

Contents

Figures

| : | Helen Johnson, Warm Ties. |

| : | Joseph Wright, The Corinthian Maid. |

| : | Benozzo Gozzoli, The Feast of Herod and the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. |

| : | Robbie Barrat, AI Generated Nude Portrait. |

| : | Pat Steir, The Brueghel Series (A Vanitas of Style) Polychrome. |

| : | Cheyney Thompson, Chromachrome. |

| : | A. H. Munsell, Scale of Hues. |

| : | Tomma Abts, Lr. |

| : | Dana Schutz, Open Casket. |

| : | Gerhard Richter, Tote. |

| : | Maria Lali, History Painting. Blue. |

| : | Johannes Phokela, Ides of March. |

| : | Dutch Room, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. |

| : | Louise Lawler, How Many Pictures. |

| : | Taus Makhacheva, Tightrope. |

| : | Cornelius Nortbetus Gijsbrechts, The Reverse of a Framed Painting. |

Introduction

Whenever we are before the image, we are before time.

The exhibition The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World that opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York on 14th December 2014 used the science fiction writer William Gibson's notion of a-temporality to describe a cultural product of our moment that paradoxically doesn't represent, through style, through content, or through medium, the time from which it comes. Through this interpretive lens, the

profligate mixing of past styles and genres can be identified as a kind of hallmark for our moment in painting, with artists achieving it by reanimating historical styles [] sampling motifs from across the timeline of 20th-century art in a single painting or across an oeuvre [].

Echoing such tendentious artistic strategies, Laura Hoptman, writing in the catalogue that accompanied the exhibition would claim that what attracts artists to painting at a time when digital technology offers seemingly limitless options with less art-historical baggage is precisely its art historical baggage []. As Hoptman's contention denotes, it would appear that the ecologies of painting today are such that questions of the object's temporality and its relationship to the past or perhaps, more specifically, a past, are for both practitioners and critics alike, a key area of focus.

To begin to unpack why such a concern has recently gained a measure of critical purchase, one would perhaps first have to acknowledge the dissolution of modernist temporalities that were premised on a linear conception of time. For example, writing in an article in Artforum in 1972, Rosalind Krauss compares the historical progression of the modernist artwork to:

a series of rooms en filade. Within each room the individual artist explored, to the limits of his experience and his formal intelligence, the separate constituents of his medium. The effect of his pictorial act was to open simultaneously the door to the next space and close our access to the one behind him. The shape

Conversely, no longer beholden to a modernist teleology that promulgated the work of art as being necessarily bound up with a trajectory of aesthetic progression, postmodernism arrested the historical advance of the object. According to Thomas McEvilley:

The formalist view of art as a series of historically necessary developmental sequences was more than discredited; insofar as it had functioned as a kind of cover story for the claim of the superiority of Western culture and the centrality of its history within the whole, that view of art came to seem not merely misguided but positively harmful and, in puritanical abreaction, a kind of force of evil.

One corollary of postmodernism privileging historical discontinuity was the tendency for it to adopt a number of appropriationist strategies that worked with any number of styles derived from any number of historical moments. By foregrounding pluralism (as opposed to the uniqueness of the modernist artifact), the claim that there could be a dominant style became increasingly contested.

As a way to counter the malaise that postmodernism had originally engendered, certain thinkers have more recently turned toward the concept of anachronism as the means by which the effects of time can be harnessed. In certain respects, anachronism as a key strategy with regard to thinking about time and the work of art provides a third way between the linear model of time associated with modernism and the ostensible temporal arbitrariness brought about by postmodernism's leveling out of various styles. Moreover, and as Keith Moxey has noted:

In weaving what has been with what is, [anachronism offers] us a different conception of time no longer dominated by the linear progression with which art history is so familiar, but one that instead erases the distinction between the observer, on one side of time, and the epoch in which the work was created, on the other. The texture of the past is threaded through an account of the work's reception in the present.

Although the relationship between anachronism and contemporary painting will be considered in closer detail within Chapter 4, at the very least it would appear to be the case that not only do instances of contemporary painting configure time differently, painters have different ways, so to speak, of telling the time. For example, beyond the tacit conviction directed toward painting's continued vitality, one Johnson, for her part acknowledges a connection with

some strategies of postwar German painting because I think they can be of use in Australia today as a means of addressing this country's fraught and unresolved relationship to history since colonization: for instance, the paintings Martin Kippenberger produced during the mid-80s, when he mobilized painting's complexities in the service of a broader cultural critique. In an Australian context, I see these sorts of strategies in the work of Juan Davila, Geoff Lowe/A Constructed World, Raquel Ormella, and Kate Smith, for example.