Contents

List of Figures

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

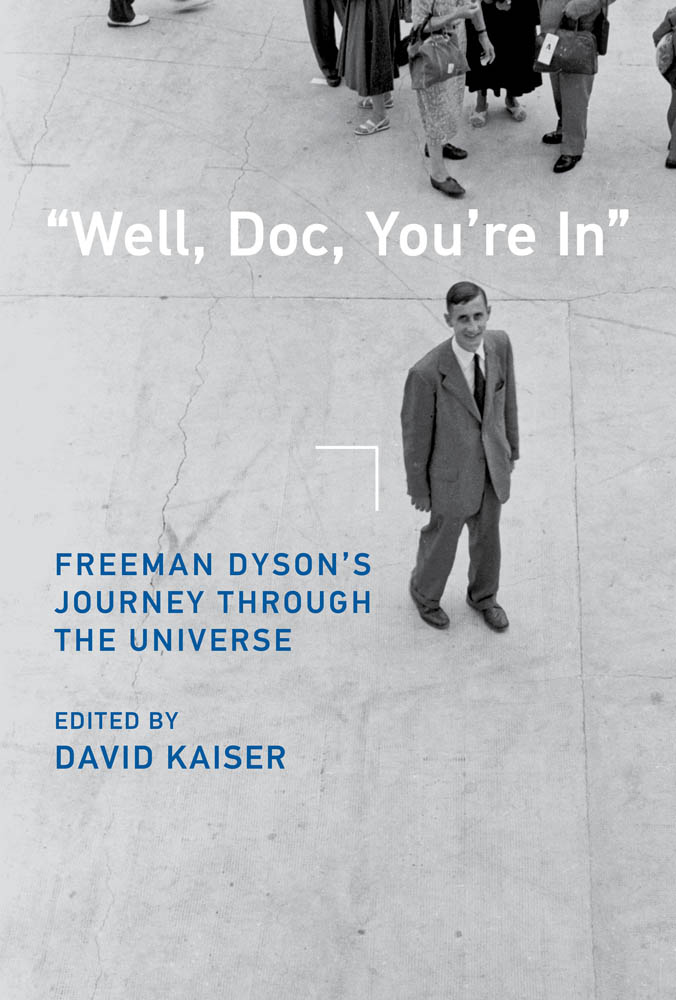

WELL, DOC, YOURE IN

Freeman Dysons Journey through the Universe

EDITED BY DAVID KAISER

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-0-262-04734-0

d_r0

CONTENTS

- David Kaiser

- Amanda Gefter

- William Thomas

- David Kaiser

- Robbert Dijkgraaf

- George Dyson

- Ann Finkbeiner

- Ashutosh Jogalekar

- Caleb Scharf

- Jeremy Bernstein

- Esther Dyson

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

DAVID KAISER

Here is a scientist who can really write, the physicist Hans Bethe observed in his review of Freeman Dysons first book, Disturbing the Universe, in 1979.

Even by physicists standards, Dysons thinking was strikingly unconstrained by the here and now. One moment he was delving into the esoterica of quantum theory, and the next, he was speculating about the logistics of alien civilizations. In the 1950s, he joined the team developing a new type of nuclear reactor, which included several novel safety features; soon after, he was designing a spacecraft propelled by nuclear bombs. (His plans were scuttled by the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty.) Many of his views were penetrating; a fewlike his insistence, late in life, that fears about rising carbon dioxide levels were misplacedremained stubbornly out of step with the scientific consensus. To the end, he was a mental adventurer, not so much iconoclastic as intellectually fearless and relentlessly curious.

I first met Dyson in January 2001. He greeted me at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he had worked, by then, for nearly a half century. Though he was in his late seventies, Dyson was elfish and spry, bounding up stairs two at a time. I was there to interview him for a book I was writing about how physicists had learned to calculate subtle effects among elementary particles using a theory known as quantum electrodynamics (QED). Dyson had played a pivotal role in those developments during the late 1940s, consolidating and pushing forward the insights of three other physicistsRichard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, and Sin-Itiro Tomonaga. These three later shared the Nobel Prize for the work, but it was Dysons contribution that made QED a workable theory.

That January afternoon, Dyson graciously sat with me for a two-hour interview, fielding my questions about the origins of QEDhow the theory had evolved in collaboration with students and colleagues. As we were wrapping up, I sheepishly asked about something more personal. Id seen some of Dysons correspondence quoted in a colleagues book: letters he had written to his parents and his sister during some of the most exciting periods of his work. Could I see them? Without hesitating, Dyson hopped out of his chair, pulled open some file cabinets, and produced several thick folders bulging with letters. Even more remarkable, he set me up with a photocopier and a spare key to his office so I could make copies of the entire collection.

The letters were spellbinding. Stretching back to the 1940s, the weekly missives conveyed the uncertainty and exhilaration of Dysons early forays into scientific research, interwoven with pitch-perfect vignettes about the people around him, such as his mentor at Cornell University, Bethe, and the irrepressible Feynman. Usually Dyson had written the letters by hand, but sometimes he had used an inexpensive portable typewriter. The originals give an impression of his quick mind at work; often stray letters appear above or below a given line, the typewriters strained mechanisms no match for the speed of Dysons thinking.

Much as his later essays would do, the letters roamed over a remarkable range of topics. His parents in England had never visited the United States, so Dyson played amateur anthropologist, sharing observations about postwar life. Thomas Dewey, the Republican governor of New York and 1948 presidential candidate, struck Dyson as very greasy during a visit to Cornells campus, while the notorious Henry Wallace delivered an electrifying speech to Dysons fellow students and teachers. Roaming beyond Ithaca, Dyson hitchhiked to New York City with friends and took long bus rides up and down the East Coast, into the Midwest, and all the way out to California. He sent thoughtful observations of race relations in Chicago, St. Louis, and Ypsilanti, Michigan, and described the endless succession of rich well-tended farms and rich ill-tended industrial cities on a long ride back East. Those early letters conveyed a thirsta physical, palpable thirstto explore.

EXPANDING HORIZONS

Soon after Dyson passed away, I began working with several colleagues to examine facets of his life and legacy. The chapters that follow unfold in rough chronological order, charting Dysons formative years, his budding interests and curiosities, and his efforts across the natural sciences, technology, and public policy. Rather than constituting a biography per sefor which Dysons autobiographical writings and Phillip Schewes Maverick Genius, published in 2013, provide valuable materialthe chapters explore Dysons particular way of thinking about deep questions, from the nature of matter, to the special challenges and opportunities afforded by nuclear power, to the origins of life and the ultimate fate of the universe.

Born in Berkshire, England, in December 1923, Dyson was a mathematical prodigy. As Amanda Gefter describes in chapter 1, That Secret Club of Heretics and Rebels, Dyson survived boarding school, found respite in musty libraries, and went on to study mathematics at the University of Cambridge. A determined autodidact, he developed a lifelong suspicion of organized curricula; he began crafting his persona as a scientific rebel at an early age. His studies at Cambridge were interrupted by war. In chapter 2, Calculation and Reckoning: Navigating Science, War, and Guilt, William Thomas explores how Dyson learned to apply his quantitative skills as an analyst in the Operational Research Section of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command during the Second World War. There, too, Dyson quickly became disillusioned with what he perceived to be an ineffective and bureaucratic organization, hidebound by hierarchy.

Back at Cambridge after the war, Dyson switched from mathematics to physics but quickly grew restless. The real excitement in the field, he thought, had shifted to the United States, and so, with the aid of a Commonwealth Fellowship from the British government, he set off to pursue graduate study at Cornell in 1947. In chapter 3, The First Apprentice, I follow Dysons extraordinary progress in a subjectquantum electrodynamicsthat had stymied the worlds most accomplished theoretical physicists for decades. Within the two years covered by his fellowship, Dyson managed to synthesize new work by Feynman, Schwinger, and Tomonaga and push well beyond each of their calculations. When a young physicist extolled Dysons contributions at a physics conference in New York City in January 1949, Feynman leaned over and announced, Well, Doc, youre in. The only catch: Dyson never bothered to complete his PhD. To the end of his life, he proudly remained Mr. Dyson.