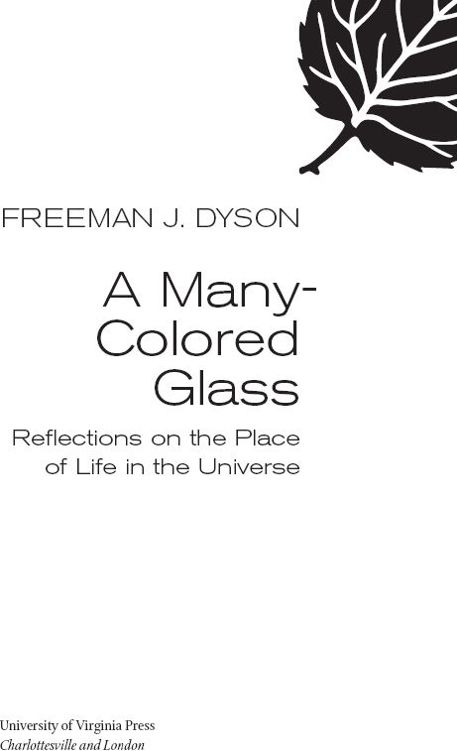

Dyson - A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe

Here you can read online Dyson - A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Charlottesville u.a, year: 2010;2004, publisher: University of Virginia Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A Many-Colored Glass

P AGE -B ARBOUR

L ECTURES

FOR 2004

University of Virginia Press

2007 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2007

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Dyson, Freeman J.

A many-colored glass : reflections on the place of life in the universe / Freeman J. Dyson.

p. cm. (Page-Barbour lectures for 2004)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8139-2663-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Life (Biology)Philosophy. 2. BiologyPhilosophy. 3. SciencePhilosophy. 4. SocietyPhilosophy. I. Title.

QH501.D97 2007

570.1dc22

2006103104

Life, like a dome of many-colored glass,

Stains the white radiance of eternity.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Adonais

Contents

Preface

This book is a collection of lectures on the general theme of life in the universe. It began with three lectures given at the University of Virginia in March 2004. These were called Page-Barbour Lectures in honor of Thomas Page and the Barbour family of Virginia. The lectures were originally funded in 1907 by Thomas Pages wife, who belonged to the Barbour family. Thomas Page was a diplomat and writer, and most of the previous lecturers have been philosophers or historians or poets. Among my distinguished predecessors were T. S. Eliot and W. H. Auden. I am the first physical scientist to give the lectures. The text of my Page-Barbour lectures is to be found in .

Since the three Page-Barbour lectures would have made a very skimpy book, I have supplemented them with other lectures given at various times and places. is from a lecture given at the Center of Theological Inquiry in Princeton in November 2003. I have edited these lectures so as to fit them together with the Page-Barbour lectures without overlapping. The result is a collection of essays rather than a coherent narrative.

The book has three main themes. The first theme is political, trying to understand the human and ethical consequences of biotechnology. The second theme is scientific, trying to understand intellectually the place of life in the universe. The third theme is personal, trying to understand the implications of biology for philosophy and religion. The first theme occupies . I have not tried to squeeze my thoughts about various aspects of science and technology into a unified theory. My reflections spill over from astronomy into ecology, and in the last chapter from neurology into theology. Life is, as Shelley said, a dome of many-colored glass, and its beauty lies in its variety.

I am grateful to the University of Virginia for the hospitality that I enjoyed while giving the Page-Barbour Lectures, and for the opportunity to publish them in this volume. I am also grateful to the institutions that gave me help and encouragement to compose the other lectures that are here included. I owe an apology to Amy Lowell, who published her first book of poems in 1912 with the title A Dome of Many-Colored Glass. I pray her forgiveness for taking a piece of her title. We both independently borrowed it from Shelley.

The three Page-Barbour lectures were given with the series title Life in the Universe. The individual lectures were A Friendly Universe (chap. 4), Looking for Life (chap. 6), and Possible Futures (chaps. 1 and 2).

were published as Heretical Thoughts about Science and Society, the Frederick S. Pardee Distinguished Lecture, November 1, 2005. This is part of the Distinguished Lecture Series published by the Frederick S. Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer-Range Future, at Boston University ( 2006 Boston University).

A more technical version of with the title Is Life Digital or Analog? was published in 2002 by the Templeton Foundation Press as a chapter in a book, The Far-Future Universe.

A more technical version of was published with the title Looking for Life in Unlikely Places: Reasons Why Planets May Not Be the Best Places to Look for Life, in the International Journal of Astrobiology 2 (2003): 10310.

was published by the Center of Theological Inquiry in its magazine Reflections 7 (Spring 2004): 3257. I learned after this book was finished that Octavia Butler died on February 24, 2006, at the age of fifty-eight. She fell dead on the path in front of her home, probably as the result of a stroke.

A Many-Colored Glass

The Future of Biotechnology

H EDGEHOGS AND F OXES

Scientists come in two varieties, hedgehogs and foxes. I borrow this terminology from Isaiah Berlin (1953), who borrowed it from the ancient Greek poet Archilochus. Archilochus told us that foxes know many tricks, hedgehogs only one. Foxes are broad, hedgehogs are deep. Foxes are interested in everything and move easily from one problem to another. Hedgehogs are only interested in a few problems that they consider fundamental, and stick with the same problems for years or decades. Most of the great discoveries are made by hedgehogs, most of the little discoveries by foxes. Science needs both hedgehogs and foxes for its healthy growth, hedgehogs to dig deep into the nature of things, foxes to explore the complicated details of our marvelous universe. Albert Einstein and Edwin Hubble were hedgehogs. Charley Townes, who invented the laser, and Enrico Fermi, who built the first nuclear reactor in Chicago, were foxes. It often happens that foxes are as creative as hedgehogs. The laser was a big discovery made by a fox. The general public is misled by the media into believing that great scientists are all hedgehogs. Some periods in the history of science are good times for hedgehogs, other periods are good times for foxes. The beginning of the twentieth century was good for hedgehogs. The hedgehogsEinstein and his followers in Europe, Hubble and his followers in Americadug deep and found new foundations for physics and astronomy. When Fermi and Townes came onto the scene in the middle of the century, the foundations were firm and the universe was wide open for foxes to explore. Most of the progress in physics and astronomy since the 1920s was made by foxes.

Another fox who played an important part in twentieth-century science was John von Neumann. Von Neumann was interested in almost everything and made important contributions to many fields. In the 1920s he found the first axiomatic formulation of set theory that was free of logical contradictions, an achievement that enabled his hedgehog friend Kurt Gdel to prove his famous theorem about the existence of undecidable propositions in arithmetic. Gdel continued to be a hedgehog and von Neumann continued to be a fox. After straightening out set theory, von Neumann invented game theory, found the first mathematically rigorous formulation of quantum mechanics, and studied the logical architecture of automatic machinery and human brains. Fifty years ago in Princeton, I watched him designing and building the first electronic computer that operated with instructions coded into the machine. He did not invent the electronic computer. The computer called ENIAC had been running at the University of Pennsylvania five years earlier. What von Neumann invented was software, the coded instructions that gave the computer agility and flexibility. It was the combination of electronic hardware with punch-card software that allowed a single machine to predict weather, to simulate the evolution of populations of living creatures, and to test the feasibility of hydrogen bombs.

I was lucky to be at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in the 1940s and 50s when von Neumanns computer project began. He invited lively young people from all over the world to start new fields of science that the computer would make possible. The biggest group were meteorologists, who started the science of climate modeling. Another group were mathematicians, who started what later became known as computer science. Another group were hydrogen bomb designers, who brought their codes secretly to run on the machine during the midnight shift. And there was Nils Barricelli, a lone biologist who ran codes simulating biological evolution. He started the science of artificial life forty years before it became fashionable. Von Neumann was interested in all these activities, but most of all in meteorology. He had grand ideas about meteorology. I remember him giving a talk about the future of meteorology. He said,

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe»

Look at similar books to A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.