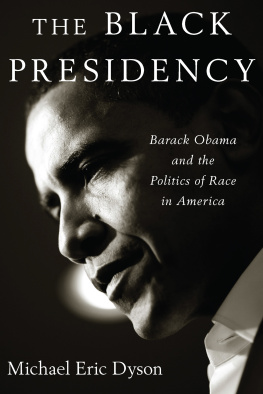

Copyright 2016 by Michael Eric Dyson

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-544-38766-9

Cover design by Brian Moore

Cover photograph Charles Ommanney/Getty Images

e ISBN 978-0-544-38642-6

v1.0216

For Marcia

|

Introduction:

The Burden of Representation

B ARACK OBAMAS BLACK PRESIDENCY HAS SHOCKED THE SYMBOL system of American politics and made the adjective in representative democracy mean something quite different than in the past. Obama provoked great hope and fear about what a black presidency might mean to our democracy. His biracial roots and black identity have been a beguiling draw and also a spur to belligerent reaction. White and black folk, and brown and beige ones, too, have had their views of race and politics turned topsy-turvy. What many Americans of all colors believe is that race fundamentally defines America and is a dividing line drawn in blood through the nations moral map. Many metaphors of race drape the nations political framework: Barack Obama argued in his famous March 2008 race speech in Philadelphia that slavery is the nations original sin, and former secretary of state Race is the most durable link in the nations chain of destiny; it is at once a damning indictment of our quest for real democracy and true justice, and also a resilient category of individual and group identityone that cannot be reduced to either mere pathology or collective pride. Race is both the midwife of glorious achievements like jazz and the black freedom movement and the abortive instrument of Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan. Race is the thing we cannot seem to do withoutand the thing that we cannot seem to get rid of.

Race is the defining feature of our forty-fourth presidents two terms in office. Obamas presidency is a lens to sharpen the details of American ideas about race and democracy. His presidency also raises the question of how much closer the election of a single black man may bring us to a more just and inclusive society. Barack Obama has finally made transparent the idea that our country cannot fully flourish without embracing a black identity that is the quintessential expression of the American character. What we all intuitively sense is that this presidency turns on their ear all the ways we have historically looked at presidencies, and perhaps, even more broadly, at our very democracy. Obama certainly bears what James Baldwin called the burden of representation.

Thomas Jefferson and James Baldwin gaze at us from immortal perches separated by two centuries and two races locked in fateful struggle. But Jefferson and Baldwin are separated only by time and race; they are united in their unrelenting sexual and political preoccupation with the other. Jefferson and Baldwin can finally be joined in the full complexity of a conversation about race and American politics across timea conversation that is constantly evoked but never fully engaged, as if it were held behind doors that are locked to everyone who would participate. And yet Obama is snared in a fascinating paradox: a man seen by many observers as the key to the locked doors of conversation about race is most reluctant to take charge and unlock the treasures of racial insight and wisdom.

What we learn about Obama says a lot about what we learn about ourselves; his racial reality is our racial reality. And it is never, ever static. That truth becomes apparent when we understand just how much we as a nation project our expectations and frustrations onto Obamas presidency, and how he effortlessly represents our deepest doubts and our most resilient hopes. We must concentrate on what Obama says and doeson what speech he gives or what policy he enacts or fails to implement. We must also grapple with what Obama literally means, what his ideas amount to, what veins of ideology or sources of racial imagination he taps when he speaks, and where we travel as a nation by welcoming or resisting the social pathways his presence lays before us.

Obamas presidency represents the paradox of American representation. Obama represents for all of us because he stands as the symbol of America to the world. He also represents to the American citizenry proof of progress in a nation that has never before embraced a black commander in chief. Yet a third sense of representation has a racial tinge, because Obama is also a representative of a black populace that, until his election, had been excluded from the highest reach of political representation. These three meanings of representation are the core of Obamas paradoxical relationship to the citizens of the country he represents: he is at once a representative of the country, a representative of the change the country has endured, and a representative of the people to whom change has been long denied and for whom that change has meant the most.

Of course critics may read black presidency as a term that denies Obama the agency and individuality that mark genuine social and moral achievement. To say black presidency is already to have reduced Obamas presidency to something less than any other presidency. But the term also imbues the presidency for the first time with the true promise of democracy on which this country was founded. The paradox of representation is thus two-sided: a member of a minority group deliberately excluded from opportunity now stands at the peak of power to represent the nation. The idea of race both qualifies and enhances the representative stature of the presidency. When it comes to race, representation in America is always an internal barometer of privilege, through the exclusion of blacks and others, while at the same time, given how central to our lives race has become, it is also an external barometer of justice.

In The Black Presidency I examine Barack Obamas political journey to tell a story about the politics of race in Americaour racial limits and possibilities, our tortured past and our complicated present, our moral conflicts and aspirations, our cherished national myths, and our contradictory political behavior. The cultural impact of Obamas lean black presidential frame will be far more enduring than partisan debates about his political career. Obama has changed the presidency itself; the ultimate seat of power has now been occupied for two terms by a man whose body translates in concrete terms our most precious democratic ideals. Obama gives African legs to the Declaration of Independence and a black face to the Constitution. Obamas black presidency cannot be erased by political will even as Congress thwarts his legislation. The paradox of representation Obama symbolizes is not up for judicial review even as the Supreme Court troubles the black vote that helped to sweep him into office.

The existence of a black presidency signals for some people an end to racial categories that have plagued America since 1619. The post-racial urge rises in a society seeking to avoid the pain of overcoming its racist legacy. Obamas presidency has defeated the post-racial myth, not with less blackness but with more of it, though it is the kind of blackness that insinuates and signifies while hiding in plain sight. The presidency is now permanently marked by difference, one that transcends Obama himself and may pave the way for a female president whose gender will be far less noteworthy for Obamas having been the first black president.

A black presidency and the politics of a lived American democracy are like a transmission and its motor: the motor creates the power and the transmission makes the power usable. A black presidency necessarily engages the identity and meaning of an American democracy that was for so long an efficient engine for excluding black participation. Some may worry that the term black presidency is code for a delegitimized presidency that undermines democratic institutions and ideas. But Obamas achievement gestures toward what the state had not allowed at the highest level before his emergence: equality of opportunity, fairness in democracy, and justice in society. Our system of government gains more legitimacy when it accommodates demands for justice and adjusts to the requirements of formal equality. Obamas presidency, paradoxically, both critiques and affirms a political order that stymied the ambitions of other black politiciansan order he now heads.

Next page