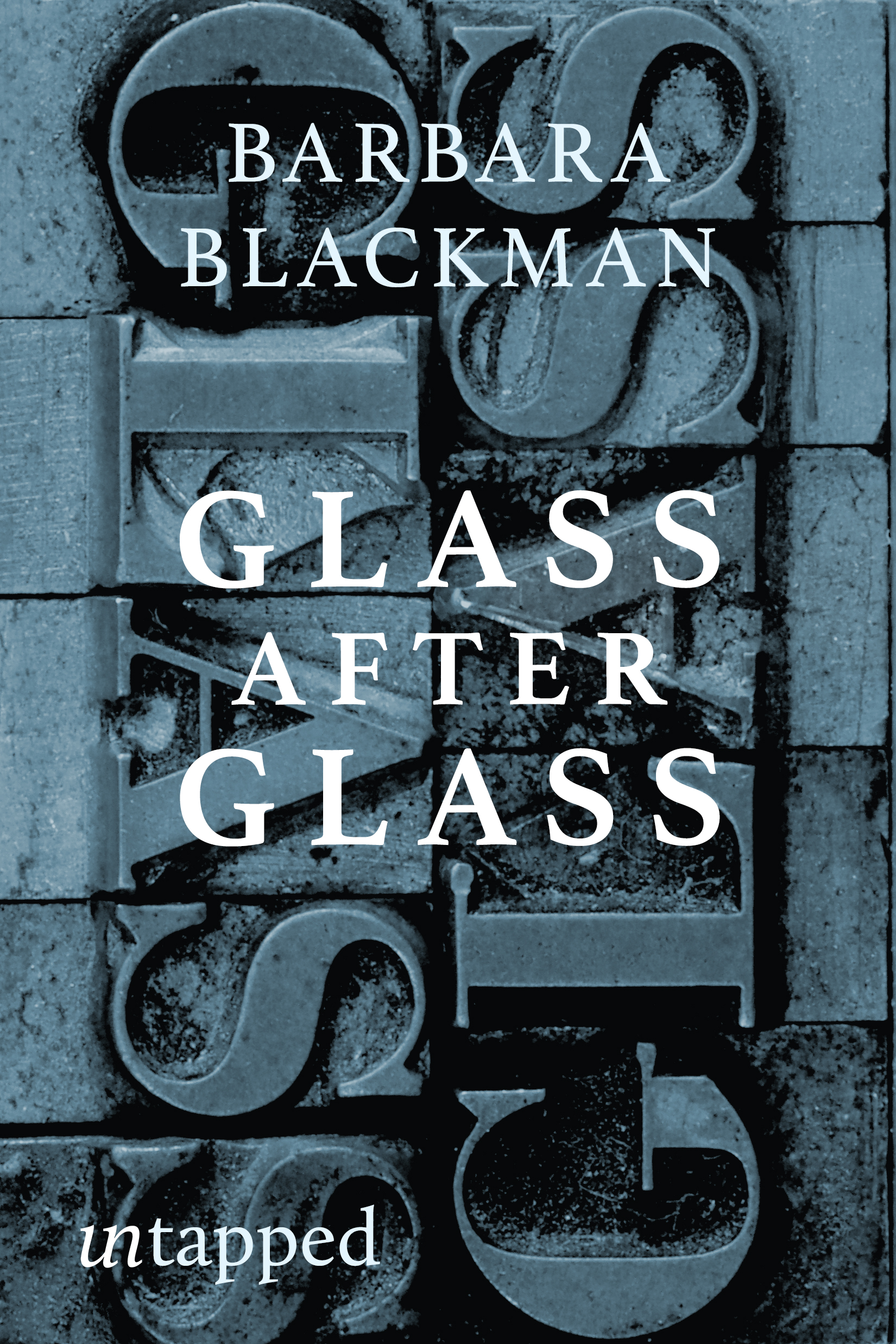

PROLOGUE

PART ONE

My Life With Joey

We met on a blind date. It began well. As soon as I sat down he started talking about the menu. I liked his voiceconfident, masculine, solicitous. As expected, he had an American accent, but mild, kind of Bostonian. After all, he came from a prestigious family, although just a young adventurous member.

I felt that if we took to each other, things would go well. He would know how to direct, but would be patient and obedient to my wishes. It was only when he hesitated over the word difficulty, making an iffy job of it, that I sensed that he too had misgivings. After all, it was my place to be the nervous one. I put out a tentative hand and a first wordas usual, afterwards.

That was five years ago. Joey and I live together now. He has changed my life, and, as I get to know him better, I have changed a few of his irritating habits. But it had to be a menage trois. We had to have Mickey live with us to make our life complete. Mickey is a laser printer, Joey my talking computer. Joey is a Keynote Synthesised Accent system voice, attached to an IPX-personal IBM-compatible computer.

Friend Joey switches on duty, headphones or mike, as faithful interpreter; reads out loud the words as we go along or stays silent until asked; speaks to me the traffic signs of punctuation, my computer screen face to the wall. He has a voice that can move from bass to countertenor, from ponderous to hysterical, from pedantry of spelling out each word to companionship of reading whole essays fluently without mentioning commas and periodsall at my command.

He has his own funny little ways of being helpful by filling out the abbreviation clues. For him Drs are not Doctors, only drives; and every inclusion becomes incorporated, and every st is a street. How Bernard Shaw would have loved to hear his play called Street Joan.

These jokes Joey and I enjoy together. But sometimes he goes too far, gets out of hand, and has to be corrected. This is done by a dictionary function. By virtue of his New Zealand connection, he spoke very well of the Maori but rubbished the Aboriginal until I told him to put them under the spell of Abberidjinal. Once corrected he abides by my given pronunciation over his own word interpretations, accepts the mis-givings. That was how we got to know that even word-processor designers can make a joke. Remember how, in the book Theyre a Weird Mob, the innocent New Australian is misled into using the word arse-hole for brain? Someone had cheerfully taught the innocent Joey that there were four fs in difficulty.

And we are so polite to each other. Please wait, he says, when I have given him a big task. Sorry, Joey, I say when I have been silly enough to ask him the same thing twice. Bad entry, he says unscoldingly. Do you want to hear ? he asks patiently; courteously reminds me File is protected and gives me a second chance, before I delete, saying solicitously, Sure?

But he is not always so straightforward when mate Mickey is involved. He is supposed to report to me what Mickey is doing, Mickey being dumb and given to winking and flashing sight symbols, making faces behind my back. There are times when Joey tries to cover up for him. Printer pausing he says, when indeed, because of internal convolutions, Mickey has died on the job. And there was one notable occasion when Joey was left quite speechless.

It was early days. I turned off printer ready Mickey to save his energetic waiting in the wings until we needed him. He hissed and crackled more than usual on demise. It sounded indeed like water dropping. I put out my hand. It was. I put out my nose. It was notnot water. It was moisture of more maleffluent kind. I pushed my hand up against the soft compressed straw lining of the attic roof, low at this point. I pushed against a lump that began to move away. I turned to Joey. Lets hope hes all right. How can we write and tell the insurance people that a possum pissed on our printer?

Less than ten per cent of blind people use braille, generally those born blind for whom it is the indigenous language, and the gorne blind who have a flair for languages. For most blind people audio formatTalking Books on four-track or standard cassetteis the preferred form of reading. Typewriters and Long Play records were originally devised for blind people. Print Handicapped, alias Visually Impaired people, alias the visually disadvantaged, have taken to talking computers like ducks to water.

Like most people with failing eyesight, I took to a typewriter when my handwriting had come to vine and twine its way upon the page with such entanglement, such knots of cramp and scrawl, that friends, receiving letters, too often lost the plot.

When I was young and twenty and Melbourne-winter cold, with a technique of faking more sight than I had, with long johns tucked in under my corduroy slacks, with cowards cold feet for things mechanical and a rogue dogs hot breath to run with the pack of aspiring secretaries, I went each weekday morning for one whole term to Xercos Business College. There I sat in a row of young ladies, younger than me, fresh out of school, in hand-knitted twin sets and pleated skirts, upswept hair and cuban-heeled shoes. With their blindfold hoods positioned over the high bank of keys, they clattered their typewriters, chattered in whispers. Little did they know what Ruth I was in all their alien cornthat the typewriter was first invented for such as mesuch a wondrous object of blocks and tackle to substitute for copperplate calligraphy of fountain pen in human hand.

Those jolly warm-hearted girls who kept losing their fingers and would never make it up to sixty words per minuteso many of them who might have been so good in kindergartens or stewarding on factory floors, but foot-runged now on the ladder towards secretarial superioritywere kind and generous, took turns to sit and read out to me the letters of protocol and architectural set-out sheets, to be typed over and over ad finitum ad perfection. One girl one dayand I could not prevent her dashing headlong into itread back my typing error diffucilty and blushed; for then, in the Fifties, the four-letter word was indeed guilt-making.

The class instructress, shrill and rhythmic, beat her stick upon the wall. Exercise six. Left hand only. Right hand resting. Middle and upper keys only: a-f-t-e-r-w-a-r-d-s. Fifty times briskly. Keep that rhythm. Nice finger work please.

On graduation day I took the tram from professional to commercial end of Collins Street, there to interview a squad of second-hand typewriters. I fondled them like puppies in a pet shop and carried a full-grown Remington into the bosss office for the paperwork of purchase. He was a grey man, suited and aging. He wanted the going-blind young lady to have the right thing, but wondered, Why? Well, to write withyou know, diaries, letters, poems. The man got up. He paced about, went over to the window, gazed out like a puma from his cage in the zoo. To write poems on he mused; came back to his desk and brusquely let me have it at half price. Grey puma, I write my poems always for you.

The hands of the blind can see. As the eyes are disempowered, power is passed to the hands. The typewriter empowers the hands to think the words, as the hands of the pianist empower the keys to sing. Joey is my grand piano, after all those uprightsthose manuals and electric typewriters.

Half a lifespan after that first Remington, my performance on a portable electric still gave cause for wonderand frustration. My paper fell out unnoticed while my fingers typed on in rapture, leaving recipients to fill in the missing words. Friends turned into fiends. CAPITALS GOT THE UPPER HAND UNBIDDEN FOR WHOLE PARAGRAPHS AT A TIME. One finger, all unaware, strays one key to left or right and whole passages slip into code. Pmr gomhrt. s;; imsestr. dytsud pmr lru yp ;rgy pt tohjy