A LSO BY F REEMAN D YSON

Dreams of Earth and Sky

A Many-Colored Glass

The Scientist as Rebel

Imagined Worlds

From Eros to Gaia

Infinite in All Directions

Origins of Life

Weapons and Hope

Disturbing the Universe

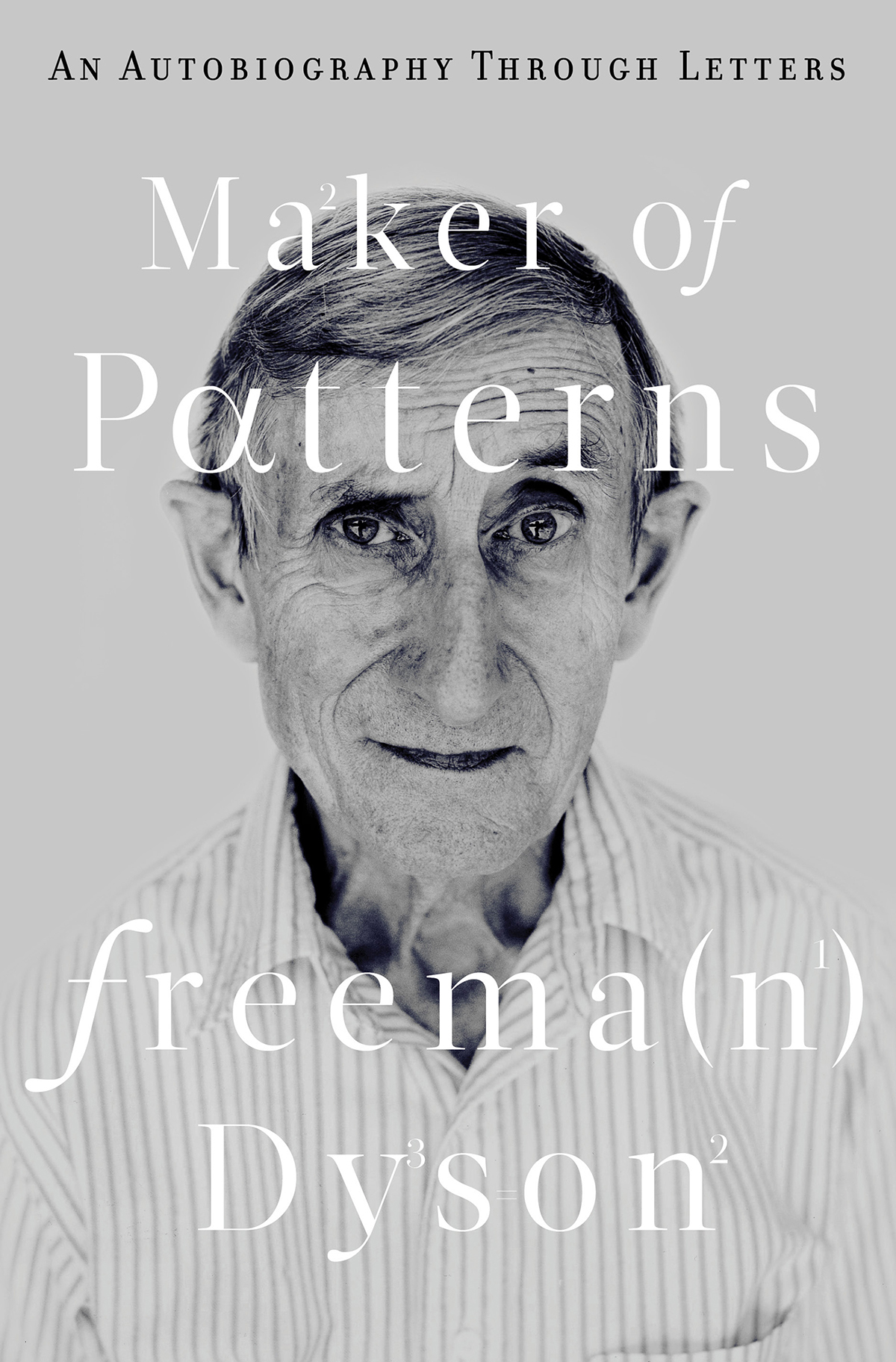

MAKER OF PATTERNS

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY THROUGH LETTERS

FREEMAN DYSON

Copyright 2018 by Freeman Dyson

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Marysarah Quinn

Production manager: Beth Steidle

JACKET DESIGN BY STEVE ATTARDO

JACKET PHOTOGRAPH IMKE LASS / REDUX PICTURES

ISBN 978-0-87140-386-5

ISBN 978-0-87140-387-2 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

A mathematician, like a painter or a poet, is a maker of patterns. If his patterns are more permanent than theirs, it is because they are made with ideas.

G ODFREY H AROLD H ARDY

CONTENTS

I N M ARCH 2017 , when this book was almost finished, my wife received a message from our twelve-year-old granddaughter: We are all metaphors in this dark and lonely world. Our daughter added her own comment, The sentiment is tempered by the fact that she has a pink Afro. The pink Afro displays a proud and joyful spirit, masking the melancholy thoughts of a teenager confronting an uncertain future. Our granddaughter is now emerging into a world strikingly similar to the world of 1936 into which I came as a twelve-year-old. Both our worlds were struggling with gross economic inequality, stubbornly persistent poverty, brutal dictators on the rise, and small wars presaging worse horrors to come. I too was a metaphor for a new generation of young people without illusions. Her declaration of independence is a pink Afro. Mine was a passionate pursuit of mathematics. I escaped from the barbaric world of Hitler and Stalin into the abstract world of Hardy. Hardy was the most famous mathematician in England when I came to him as a student in 1941 . He taught me to be a maker of patterns. An even greater maker of patterns was the Indian genius Srinivasa Ramanujan, who had come to Hardy as a student in 1914 and died at age thirty-two in 1920 . Through Hardy, I entered Ramanujans magical world. My first discoveries were concerned with the numbers and which play special roles in the weird arithmetical patterns of Ramanujan.

Afterwards I found patterns of comparable beauty in the dance of electrons jumping around atoms. Patterns as elegant as those of Ramanujan had been discovered in the world of physics by Paul Dirac, whose lectures on quantum mechanics I also attended. Dirac was one of the pioneers who had entered the strange new world of quantum physics, where strict causality is abandoned and atomic events occur by chance. The idea that chance governs nature was then still open to question. In the world of human affairs, Lev Tolstoy asked the same question, whether free choice prevails. While Dirac proclaimed free choice in the world of physics, Tolstoy denied it in the world of history. The idea that Dirac called causality, Tolstoy called Providence. At the end of his War and Peace , he wrote a long philosophical discussion, explaining why human free will is an illusion and Providence is the driving force of history. When I was a student in Cambridge, the same Providence that had destroyed Napoleons army in Russia in 1812 was destroying Hitlers army in Russia in 1943 . I was reading Tolstoy and Dirac at the same time.

The words maker of patterns had for Hardy a double meaning. Patterns could be made with words as well as with ideas, with books as well as with theorems. I once asked him why in his old age, when he was sixty-five and I was eighteen, he had stopped exploring new mathematics and was spending his time writing books. He answered without hesitation, Young men should prove theorems: old men should write books. He took pride in his style as a writer. He was a maker of patterns in English prose as well as in the theory of numbers. In my later life I followed his example. As a young man I wrote technical papers, exploring patterns of ideas in mathematics and physics. As an old man I write books, exploring patterns of words in literature and history.

The letters collected in this book record a cycle in the history of the world from 1936 to 1978 , from the civil war in Spain to the rise of Gorbachev in the Soviet Union. This was a cycle rolling from doom and gloom in the 1930 s, to death and disaster in the 1940 s, to fear and trembling in the 1950 s, to smaller disasters in the 1960 s, to recovery and promise in the 1970 s. Contrasting with this cycle of death and rebirth in the political world, there was steady progress and a continued succession of major advances in the world of science. Two discoveries transformed our views of the biological and physical worlds. The discovery of the double helix structure of the DNA molecule by Francis Crick and Jim Watson in 1953 made the basic processes of life suddenly accessible to study with the tools of physics and chemistry. The mysteries of biological reproduction and heredity could be translated into testable molecular models. The discovery of the cosmic background radiation by Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson in 1964 opened the entire physical universe to our observation. Suddenly the whole universe back to its beginnings was visible to our instruments.

In 1968 I read The Double Helix , the story written by Watson describing how he and Crick discovered the secret of life. The secret of life, as they proudly boasted after they made the discovery, was the structure of the DNA molecules that carry the genetic information in every cell of every living creature larger than a virus. The helical structure, with the genetic information written backward and forward in two complementary strands around the helix, gives the molecules the ability to replicate themselves precisely when the cell divides. The two daughter cells are born with exact copies of the mothers genetic information. Watsons book tells in vivid detail how the discovery happened, not by logical scientific reasoning but in a personal drama with real human characters. He brings the characters to life with verbatim accounts of their conversations, stumbling and squabbling as they grope their way toward the truth.

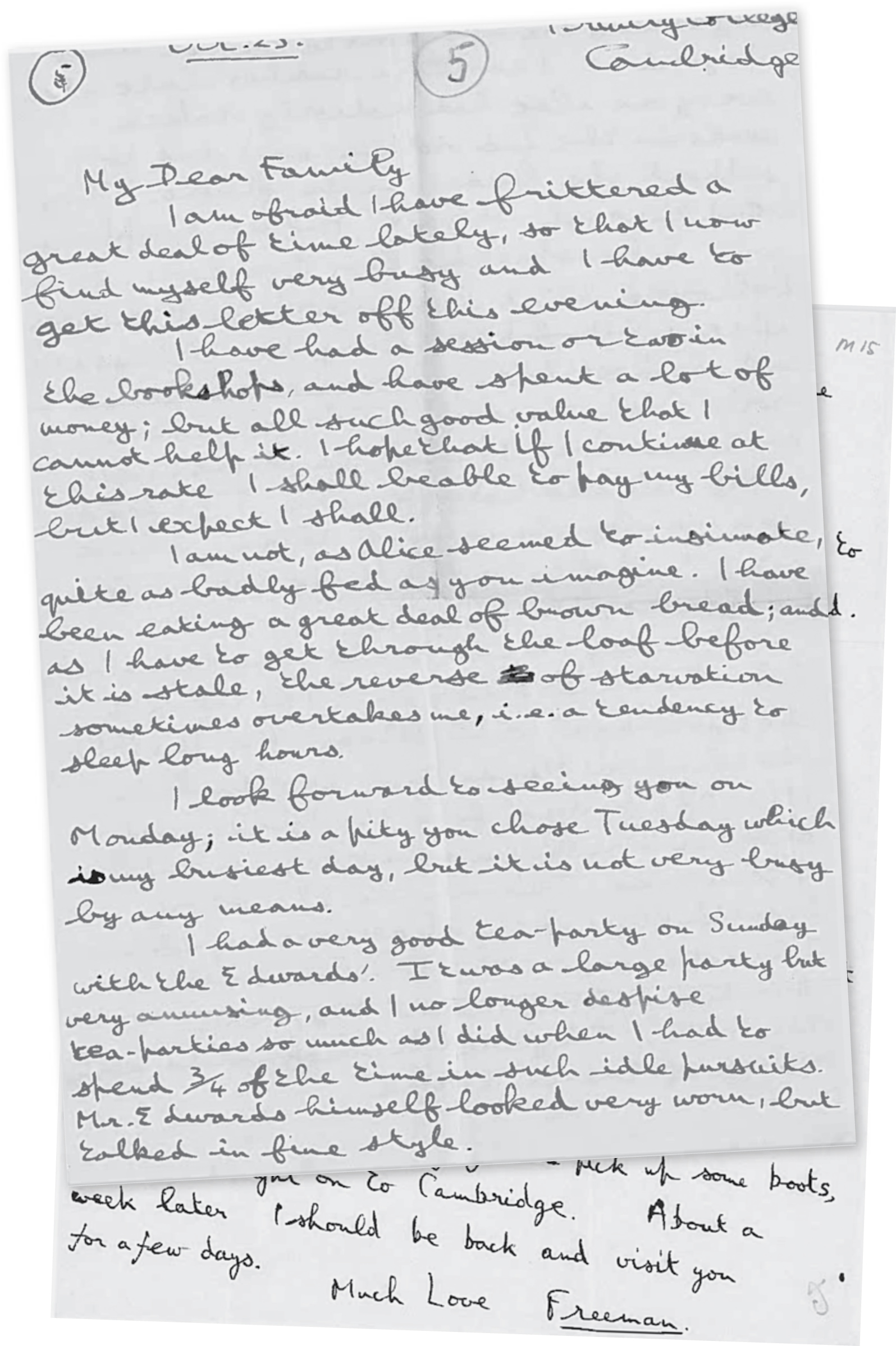

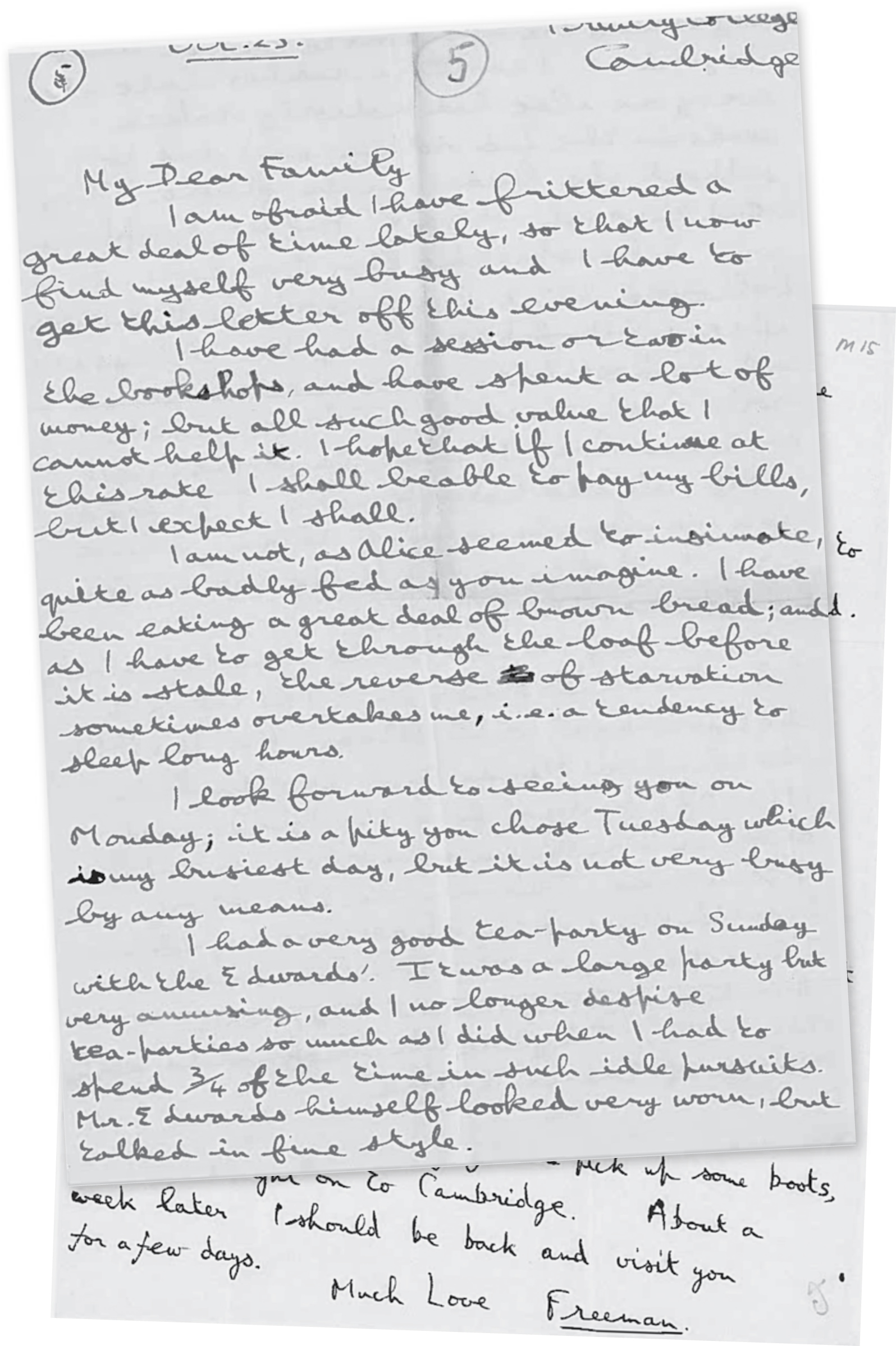

Soon after I read Watsons book, I met him in person. I asked him how he could possibly remember the details of the conversations and arguments that he put into his story. He answered, Oh, that was easy. I wrote a letter every week to my mother in America describing my life in England, and she kept the letters. I had been writing a letter every week to my parents in England, describing my life in America. That same day I wrote to my mother, urging her to keep the letters. She kept them, giving me the raw material for this book.

I do not have any great discovery like the double helix to describe. The letters record the daily life of an ordinary scientist doing ordinary work. I find them interesting because I had the good fortune to live through extraordinary historical times with an extraordinary collection of friends. Letters are valuable witnesses to history because they are written without hindsight. They describe events as they appeared to the participants at the time. Later memories of the same events may be seriously distorted by hindsight. When I compare my memories with the letters, I see that I not only forget things, I also remember things that never happened.

Next page