Copyright 2021 of new material by Karen Swallow Prior

All rights reserved.

Printed in China

978-1-4627-9667-0

Published by B&H Publishing Group

Nashville, Tennessee

Dewey Decimal Classification: 248.84

Subject Heading: LOVE / PROVIDENCE AND GOVERNMENT OF GOD / CHRISTIAN LIFE

Cover design and illustration by Ligia Teodosiu.

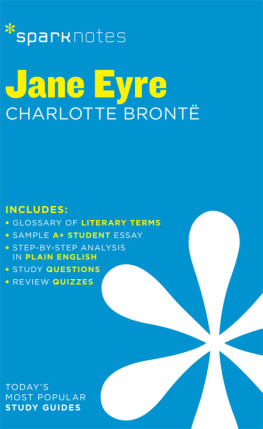

Manuscript used of Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bront was published in 1848.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 24 23 22 21

Note to the Reader

The introduction below is written to enlighten and assist both those who have previously read Jane Eyre and those who have not. In consideration of the latter, spoilers have been avoided in the introduction so that new readers may experience the delight of surprise and discovery that all good books hold. The introduction is intended to be a true introduction to the work, one that will equip new readers and returning ones with background and knowledge that will appreciate understanding and appreciation of the work without giving the story away. The discussion questions at the end of each volume address events that occur in the story and are designed for use after each section has been read.

Footnotes are provided to define or explain most archaic words and usages. Some of the terms explained are repeated throughout the text, but they are defined only once, the first time they appear.

INTRODUCTION

Introduction to the Author

Unlike her famous character, Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bront grew up surrounded by a loving and nurturing family. Charlottes Irish father, Patrick Bront, moved to England to attend Cambridge, took Holy Orders in the Church of England, and eventually accepted an appointment as rector of the village of Haworth in Yorkshire, located in Northern England. The growing Bront family made their home in the churchs parsonage, alongside desolate, rolling moors where the Bront children could roam freely and let their imaginations soar. The four youngest children drew upon their adventures to conjure fantastical worlds with complex mythologies, maps, histories, and characters that filled the pages of their notebooks.

But even the most magical of childhoods was not enough to shut out death, an early and frequent visitor to the Bront home. The first to be taken was the childrens mother, Maria Bront, who died in 1821 from uterine cancer, shortly after the birth of the last of her six children: Maria (born in 1814), Elizabeth (1815), Charlotte (1816), Branwell (1817), Emily (1818), and Anne (1820). In 1824, the widowed Rev. Bront enrolled the four oldest girlsMaria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, and Emilyin an austere boarding school that served the daughters of clergymen. It wasnt long before Maria and Elizabeth contracted tuberculosisa highly contagious bacterial infection that is easily carried and transmitted by those who have no symptomsand were sent home to die. Rev. Bront pulled Charlotte and Emily out of the school and brought them home, just in time, it seems, to save their lives.

The Bront home cultivated learning and creativity. Rev. Bront was a published poet and strove to give his children a good education. Despite the terrible outcome of her first school, Charlotte was later sent to another, Roe Head, where she was prepared for an occupation as a teacher or governess, the only roles open to women at that time besides wife and mother. Charlotte loved being a student, but her nature was not inclined toward teaching. She returned to Roe Head in 1835 where she taught just a few years, longing each day for the lessons to end so that she could return to writingthe only occupation she dreamed of. When one of her students interrupted her thoughts in the classroom one day, she

Charlotte and her brother, Branwell, each sent their poetry to a famous poet they admired, daringly hoping to receive feedback and perhaps encouragement. Charlotte chose Robert Southey, Britains poet laureate, a writer in the Romantic tradition that Charlotte and her siblings loved and emulated. The beginning of her letter displays an endearing, if melodramatic, youthful passion:

Sir,I most earnestly entreat you to read and pass your judgment upon what I have sent you, because from the day of my birth to this the nineteenth year of my life, I have lived among secluded hills, where I could neither know what I was, or what I could do. I read for the same reason that I ate or drank; because it was a real craving of nature.

After a few torturous months, Southeys response arrived. You evidently possess & in no inconsiderable degree what Wordsworth calls the faculty of verse, he wrote. I am not depreciating it when I say that in these times it is not rare. How exciting it must have been for Charlotte to receive such praise from the nations leading poet! But these laudatory words were followed by a discouraging admonition:

... there is a danger of which I would, with all kindness and all earnestness, warn you.... Literature cannot be the business of a womans life, and it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure will she have for it, even as an accomplishment and a recreation. To those duties you have not yet been called, and when you are you will be less eager for celebrity. You will not seek in imagination for excitement, of which the vicissitudes of this life, and the anxieties from which you must not hope to be exempted, be your state what it may, will bring with them but too much.

It took a couple of weeks for Charlotte to compose a reply. The opening lines reveal her sense of humiliation:

At the first perusal of your letter, I felt only shame and regret that I had ever ventured to trouble you with my crude rhapsody; I felt a painful heat rise to my face when I thought of the quires of paper I had covered with what once gave me so much delight, but which now was only a source of confusion...

After defensively stating her dutiful intention of becoming a governess, she added,

In the evenings, I confess, I do think, but I never trouble any one else with my thoughts.... I have endeavoured not only attentively to observe all the duties a woman ought to fulfil, but to feel deeply interested in them. I dont always succeed, for sometimes when Im teaching or sewing I would rather be reading or writing; but I try to deny myself... Once more allow me to thank you with sincere gratitude. I trust I shall never more feel ambitious to see my name in print: if the wish should rise, Ill look at Southeys letter, and suppress it.

It is difficult to determine when reading them today just how earnest (or ironic) a tone to read into these lines. Detecting a tinge of sarcasm is tempting. But whatever Bronts posture may have been in penning the words, her ambitions were not ultimately suppressed by Southey.

In 1839, Bront turned down two offers of marriage, both from clergymen. She seriously considered the first proposal, from the brother of a close friend, but concluded she did not love him as much as she should to be his wife, nor did she believe she could make him happy. The second offer, which she also rejected, was from a clergyman she had met only once. It seems that the sort of passion she wrote about was one she sought for her own life.

Between these two proposals, Charlotte took an ill-fitted and short-lived post as a governess. Soon she and her sisters hatched a plan to open their own school. So in 1842, Charlotte and Emily traveled to Brussels to hone their skills in French and German. When the admiration Charlotte developed for her teacherthe older and married head of the schoolgrew into a romantic attraction, the situation turned sour. The warmth with which her teacher and his wife first treated Charlotte cooled, and Charlotte eventually returned home to overcome her unrequited love. The Bronts attempt to start a school drew no students, and the endeavor was over before it began. But because Charlottes auntwho had helped Rev. Bront raise the children after their mothers deathleft an inheritance to the young women, though none of them had married, they at least possessed a little to live on.