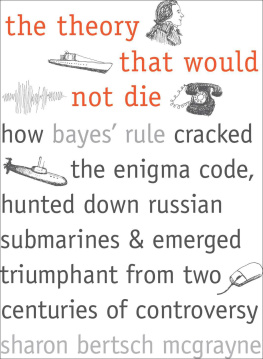

the theory that would not die

other books by

sharon bertsch mcgrayne

Prometheans in the Lab: Chemistry and the Making

of the Modern World

Iron, Natures Universal Element: Why People Need

Iron and Animals Make Magnets (with Eugenie V.

Mielczarek)

Nobel Prize Women in Science: Their Lives, Struggles,

and Momentous Discoveries

the theory that would not die

how bayes rule cracked

the enigma code,

hunted down russian

submarines, & emerged

triumphant from two

centuries of controversy

sharon bertsch mcgrayne

The Doctor sees the light by Michael Campbell is reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons; the lyrics by George E. P. Box in chapter 10 are reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons; the conversation between Sir Harold Jeffreys and D. V. Lindley in chapter 3 is reproduced by permission of the Master and Fellows of St. Johns College, Cambridge.

Copyright 2011 by Sharon Bertsch McGrayne. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Designed by Lindsey Voskowsky. Set in Monotype Joanna type by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McGrayne, Sharon Bertsch.

The theory that would not die : how Bayes rule cracked the enigma code, hunted down Russian submarines, and emerged triumphant from two centuries of controversy / Sharon Bertsch McGrayne.

p. cm.

Summary: Bayes rule appears to be a straightforward, one-line theorem: by updating our initial beliefs with objective new information, we get a new and improved belief. To its adherents, it is an elegant statement about learning from experience. To its opponents, it is subjectivity run amok. In the first-ever account of Bayes rule for general readers, Sharon Bertsch McGrayne explores this controversial theorem and the human obsessions surrounding it. She traces its discovery by an amateur mathematician in the 1740s through its development into roughly its modern form by French scientist Pierre Simon Laplace. She reveals why respected statisticians rendered it professionally taboo for 150 yearsat the same time that practitioners relied on it to solve crises involving great uncertainty and scanty information, even breaking Germanys Enigma code during World War II, and explains how the advent of off-the-shelf computer technology in the 1980s proved to be a game-changer. Today, Bayes rule is used everywhere from DNA de-coding to Homeland Security. Drawing on primary source material and interviews with statisticians and other scientists, The Theory That Would Not Die is the riveting account of how a seemingly simple theorem ignited one of the greatest controversies of all timeProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-16969-0 (hardback)

1. Bayesian statistical decision theoryHistory. I. Title.

QA279.5.M415 2011

519.542dc22

2010045037

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

When the facts change, I change my opinion. What do you do, sir?

John Maynard Keynes

contents

preface and note to readers

In a celebrated example of science gone awry, geologists accumulated the evidence for Continental Drift in 1912 and then spent 50 years arguing that continents cannot move.

The scientific battle over Bayes rule is less well known but lasted far longer, for 150 years. It concerned a broader and more fundamental issue: how we analyze evidence, change our minds as we get new information, and make rational decisions in the face of uncertainty. And it was not resolved until the dawn of the twenty-first century.

On its face Bayes rule is a simple, one-line theorem: by updating our initial belief about something with objective new information, we get a new and improved belief. To its adherents, this is an elegant statement about learning from experience. Generations of converts remember experiencing an almost religious epiphany as they fell under the spell of its inner logic. Opponents, meanwhile, regarded Bayes rule as subjectivity run amok.

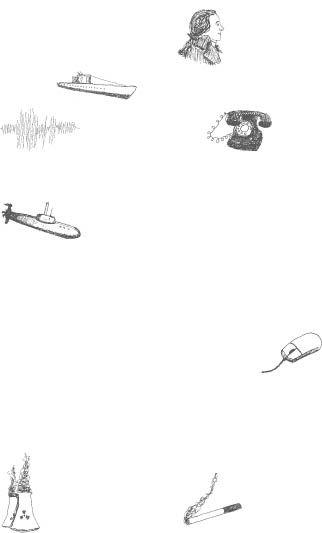

Bayes rule began life amid an inflammatory religious controversy in England in the 1740s: can we make rational conclusions about God based on evidence about the world around us? An amateur mathematician, the Reverend Thomas Bayes, discovered the rule, and we celebrate him today as the iconic father of mathematical decision making. Yet Bayes consigned his discovery to oblivion. In his time, he was a minor figure. And we know about his work today only because of his friend and editor Richard Price, an almost forgotten hero of the American Revolution.

By rights, Bayes rule should be named for someone else: a Frenchman, Pierre Simon Laplace, one of the most powerful mathematicians and scientists in history. To deal with an unprecedented torrent of data, Laplace discovered the rule on his own in 1774. Over the next forty years he developed it into the form we use today. Applying his method, he concluded that a well-established factmore boys are born than girlswas almost certainly the result of natural law. Only historical convention forces us to call Laplaces discovery Bayes rule.

After Laplaces death, researchers and academics seeking precise and objective answers pronounced his method subjective, dead, and buried. Yet at the very same time practical problem solvers relied on it to deal with real-world emergencies. One spectacular success occurred during the Second World War, when Alan Turing developed Bayes to break Enigma, the German navys secret code, and in the process helped to both save Britain and invent modern electronic computers and software. Other leading mathematical thinkersAndrei Kolmogorov in Russia and Claude Shannon in New Yorkalso rethought Bayes for wartime decision making.

During the years when ivory tower theorists thought they had rendered Bayes taboo, it helped start workers compensation insurance in the United States; save the Bell Telephone system from the financial panic of 1907; deliver Alfred Dreyfus from a French prison; direct Allied artillery fire and locate German U-boats; and locate earthquake epicenters and deduce (erroneously) that Earths core consists of molten iron.

Theoretically, Bayes rule was verboten. But it could deal with all kinds of data, whether copious or sparse. During the Cold War, Bayes helped find a missing H-bomb and U.S. and Russian submarines; investigate nuclear power plant safety; predict the shuttle Challenger tragedy; demonstrate that smoking causes lung cancer and that high cholesterol causes heart attacks; predict presidential winners on televisions most popular news program, and much more.

How could otherwise rational scientists, mathematicians, and statisticians become so obsessed about a theorem that their argument became, as one observer called it, a massive food fight? The answer is simple. At its heart, Bayes runs counter to the deeply held conviction that modern science requires objectivity and precision. Bayes is a measure of belief. And it says that we can learn even from missing and inadequate data, from approximations, and from ignorance.

Next page