A NTHONY W ALTON

Mississippi

Anthony Walton studied at Notre Dame and Brown University and currently lives in Brunswick, Maine.

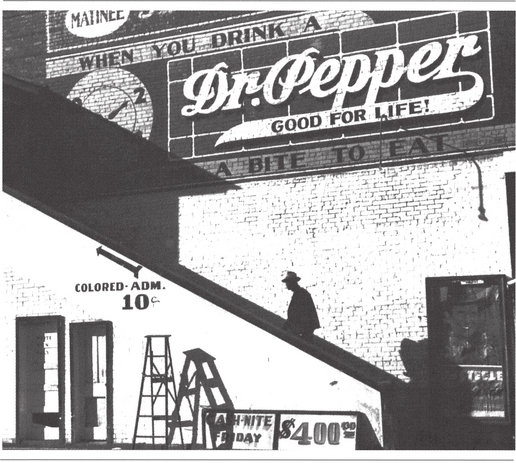

M ovie theater, Belzoni, Mississippi, 1939

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, FEBRUARY 1997

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, FEBRUARY 1997

Copyright1996 by Anthony Walton

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1996.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Dutton Signet and Sanford J. Greenburger Associates: Excerpt from This Little Light of Mine by Kay Mills, copyright 1993 by Kay Mills. Reprinted by permission of Dutton Signet, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc., and Sanford J. Greenburger Associates.

HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.: After Winter from The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown, edited by Michael S. Harper, copyright 1980 by Sterling A. Brown; Southern Road from The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown, edited by Michael S. Harper, copyright 1932 by Harcourt Brace & Co., copyright renewed 1960 by Sterling Brown (originally appeared in Southern Road). Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

King of Spades Music: Excerpts from Come On in My Kitchen, Drunken Hearted Man, Love in Vain Blues, Me and the Devil Blues, Stones in My Passway, Terraplane Blues, and Walkin Blues, words and music by Robert L. Johnson, copyright 1978, 1991 by King of Spades Music. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of King of Spades Music.

Random House, Inc.: Excerpt from Mississippi from Requiem for a Nun by William Faulkner, copyright 1951 by William Faulkner. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc.

All photographs are by Marion Post Wolcott. Used by permission of the Library of Congress, except the photographs on , which are used by permission of the Estate of Marion Post Wolcott.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Walton, Anthony, [date]

Mississippi : an American journey / by Anthony Walton.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-48831-2

1. Afro-AmericansMississippiHistory.

2. MississippiRace relations.

3. Walton, Anthony, [date]. I. Title.

F350.N4W35 1996

976.200496073dc20 95-32031

Random House Web address: http://www.randomhouse.com/

v3.1

for Claude, for Dorothy

for Claude and Dorothy

nobody knows the trouble Ive seen

I sing,

only to weep again the pity of this house

Aeschylus, Oresteia

Wellohwellohwellohwellohwell

Blues refrain

Contents

Prologue

I am walking down a side street toward the courthouse and town square of Holly Springs, Mississippi. It is a sweltering afternoon in June 1991. Eyeing the streets tired pastel and brick buildings, I can think of nothing more than air-conditioning and a cold drink. But my father, who is with me, is angry; he begins to recount the events of a Christmas Eve forty years ago.

Right here. He stops and points at a battered gray door that is now the rear entrance of a shuttered restaurant. Right here, he says again, this used to be the colored waiting room at the bus station. James was in here, right here. His index finger hangs in the air, twitching in accusation. James Crump was a school and childhood friend of my fathers, fifteen or sixteen years old at the time of which he speaks. Wed been celebrating Christmas Eve, you know, blowing off some steam, and James was a little high, he was a little happy. We went into the bus station and James was singing and clapping his hands. He was just a boy, you know, having fun, but somebody called the sheriff and complained. I never found out who.

My father starts walking again, narrowing his eyes, oblivious to the heat. The sheriff, his name was Holbrooks, came in the front door through the white folks side, and somebody yelled, James, Holbrooks is coming! James got scared and bolted out that door there. My father, fifty-six, massive and graying, his face a mask of weary experience, turns back and looks for a long moment.

Then he run up this street here as fast as he could. Meantime, Holbrooks come back out the front door and saw James, James wasnt no farther than that blue van over there. He points to a truck a hundred feet away. And Holbrooks pulled his .38 and shot the boy in the back. He didnt say Stop!nothing.

Mopping sweat from our eyes, we cross the street over to the courthouse, past cars circling the square, people taking care of Saturday business. My father points at a spot on the pavement. Right there. Thats where he fell, dead, on Christmas Eve.

ONE

Crossing the River

T HE BRIDGE over the Mississippi River at Natchez is a matter-of-fact crossing, two massive steel spans cantilevered between Adams County, Mississippi, and Concordia County, Louisiana. The bridge is not much different from river crossings Ive encountered elsewhere, as far north as Minnesota; here in the South, of course, the water is very wide, and has taken on a dull, gray-brown cast. The gray is from the muggy, slightly overcast sky, the brown from mud washed in by recent spring rains. I dont see any of the canoes, rafts, warships or steamboats of river lore, only a barge pushed by a tug off in the distance to the south.

Eastbound on U.S. 84 from Vidalia, Louisiana, just over the bridge, its a quick left onto Business 84, two lanes that wind up a steep incline and through two weathered imitation Greek columns. The columns I take as an unofficial welcome to and boundary of the city of Natchez. From where I stand, on a splash of gravel alongside the road, the river reflects like quicksilver. The bridge presents an unremarkable Friday afternoon scene, an early summer coming and going of commuters, commercial vehicles and people arriving or leaving for the weekend; a day like most others in a small town in North America. For me, though, the just-completed crossing is of tremendous consequence: I have gone over a river from familiar places and into the state of Mississippi.

If you look on a globe, or a good world map, between North and South America and between the Atlantic and the Pacific, you will see the Gulf of Mexico. Then, locating the city of New Orleans at the northern edge of this body of water, you can trace the ninetieth meridian north toward Memphis. The line you trace, between the thirtieth and thirty-fifth parallels, will roughly bisect the twentieth state in the Union, the poorest by most measures, a jurisdiction of eighty-two counties and 47,716 square miles, home to something over two million citizens.

As your finger slides youll pass place-names like McComb, Poplarville and Natchez, Philadelphia, Clarksdale and Vicksburg, each name searing a scream in the minds and memories of people like me, black Americans. Mississippi can be considered one of the most prominent scars on the map of this country. When you trace the ninetieth meridian from New Orleans to Memphis youre fingering a scar, and that is why I arrive in Natchez with some trepidation. I intend to explore that scar.

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, FEBRUARY 1997

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, FEBRUARY 1997