Age and Guile

Beat Youth, Innocence,

and a Bad Haircut

Also by P. J. ORourke

Modern Manners

The Bachelor Home Companion

Republican Party Reptile

Holidays in Hell

Parliament of Whores

Give War a Chance

All the Trouble in the World

The American Spectators Enemies List

Eat the Rich

The CEO of the Sofa

Age and Guile Beat Youth, Innocence, and a Bad Haircut

P. J. ORourke

Copyright 1995 by P. J. ORourke

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ORourke, P.J.

Age and guile beat youth, innocence, and a bad haircut: twenty-five years of P.J. ORourke.

Partial Contents: Juvenilia delinquent: underground press, 1970-1972The truth about the Sixties and other fictionDays of wage: National lampoon, 1971-1981Drives to nowhere: Automotive journalismEssays, prefaces, speeches, reviews, and things jotted on napkinsCurrent And recurrent events.Bad sports.

ISBN 0-87113-653-8 (pbk.)

1. ORourke, P.J. 2. JournalistsUnited States

I. Title.

PN4874.058A38 1995 814.54dc20 95-16430

DESIGN BY LAURA HAMMOND HOUGH

ILLUSTRATION ON TITLE PAGE BY ALAN ROSE

Atlantic Monthly Press

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

02 10 9 8 7 6 5

In Memory of

Dennis Loy

1938-1994

Acknowledgments

Twenty-five years of writing for a living leave me with a lot of people I need to thankor a lot of blame I need to spread around. However the reader may feel, Im grateful to those who helped me avoid a real job. First I would like to thank my cousin Dennis Loy, to whose memory this book is dedicated. Dennis became my friend, as opposed to relative, when I was in high school and he had just finished studying at the Art Institute in Chicago. He was the only person in my family to have read a book all the way through, for fun. Dennis was an enthusiastic audience and unpatronizing patron of even my most labored neophyte efforts. When I showed up in New York in 1971 with exactly fifteen dollars, he gave me a place to stay. I would have surely, and deservedly, starved (and frozen) that winter if it hadnt been for his help.

In college my first love, Bonnie Hall, had been equally generous. She actually thought I had something to say. She even went so far as to listen to me say it. There are no kinder or better people in the world than those who listen to you when youre eighteen.

Important, though less witting, assistance was given to me by the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship board. I had been nominated for one of these scholarship plums and went through the various rounds of elimination until I reached the final cut, an oral examination to be conducted in Columbus, Ohio.

I arrived in Columbus the night before the interview and went out beer drinking and pot smoking until all hours. I was supposed to be in the offices of the Ohio State University English Department at 9:00 A.M. I came to on somebodys couch at 9:15, pulled on my Strohs-drenched jeans and a sweatshirt reeking of sinsemilla, and rushed, unshaved, unwashed, and unregenerate, to the campus. I was shown into a seminar room and placed on a hard chair facing a conference table behind which sat five or six middle-aged worthies with notepads. I remember only one of the questions.

WORTHY: Which literary critic has had the most profound influence on your thinking?

ME:

I could not think of the name of a single literary critic. Not Roland Barthes, not John Crowe Ransom, not even R. P. Blackmur, from whom I cribbed my entire junior thesis on Henry James.

ME: Henry David Thoreau.

WORTHIES (more or less in unison): Henry David Thoreau wasnt a literary critic.

ME: His whole life was an act of literary criticism.

Well, it was 1969. Bullshit was an intellectual mainstay of the era. And I became a Woodrow Wilson Fellow.

This allowed me to get my M.A. in English at Johns Hopkins by attending something called The Writing Seminar. It was a creative writing program of the way-creative kind run by a poet named Elliot Coleman. Colemans distinction was either that he was Ezra Pounds only friend or that he was the only friend of Ezra Pound who wrote worse poetry than Ezra did. Maybe both. The Seminar possessed its good and bad points. I had, at age twenty-two, the complete luxury of writing anything I wanted with no worry about a paycheck and no thought of a public other than Professor Coleman (and, by extension, Ezra Pound). That was the bad point. The results were not as gruesome as having, at age twenty-two, the complete luxury of spending anything I wanted or screwing anything I wanted, but almost. The good point was that the Seminars course work entailed reading only such high modernists as John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Thomas Pynchon, Jorge Borges, etc. A couple of semesters of this and even a twenty-two-year-old was cured of an interest in art.

But I seem to have digressed from the acknowledged purpose of an Acknowledgments page and wandered into autobiography or some other form of self-gratification. And it is others I mean to gratify if I can. Michael Carliner, whod started a Baltimore weekly newspaper named Harry, gave me my first writing assignment while I was still at Hopkins. And my fellow Seminar student Denis Boyles started another newspaper and gave me a second assignment. My career was launched. That is, I had gained the privilege of getting a free handful of either of these papers and standing on street corners selling them for twenty-five cents each until I had enough money for beer.

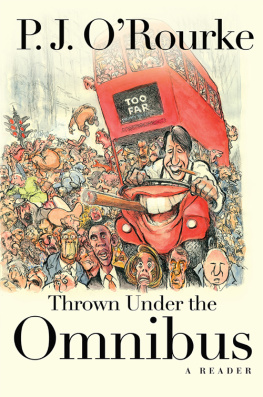

I stayed in Baltimore, off and on, for two years, working with Tom DAntoni, who managed to keep Harry going well into the 1970s, and with graphic artist Alan Rose, who has been my collaborator on such projects as the National Lampoon High School Yearbook Parody, the National Lampoon Sunday Newspaper Parody, and The Bachelor Home Companion and who drew the illustration on the title page of this book, which a certain significant other of mine wont let me get as a tattoo.

Some time about 1971 Bob Singer, a writer for the East Village Other, wandered into Baltimore and convinced me that I should try my hand at EVO, which was the grandaddy of the underground newspapers, dating all the way back to 1965. Poor Bob languishes today in a California prison for something to do with smokable substances, notamazingly enough, considering Californian attitudestobacco. Another EVO writer, Ray Shultz, got me a job on a legitimate weekly called the

Next page