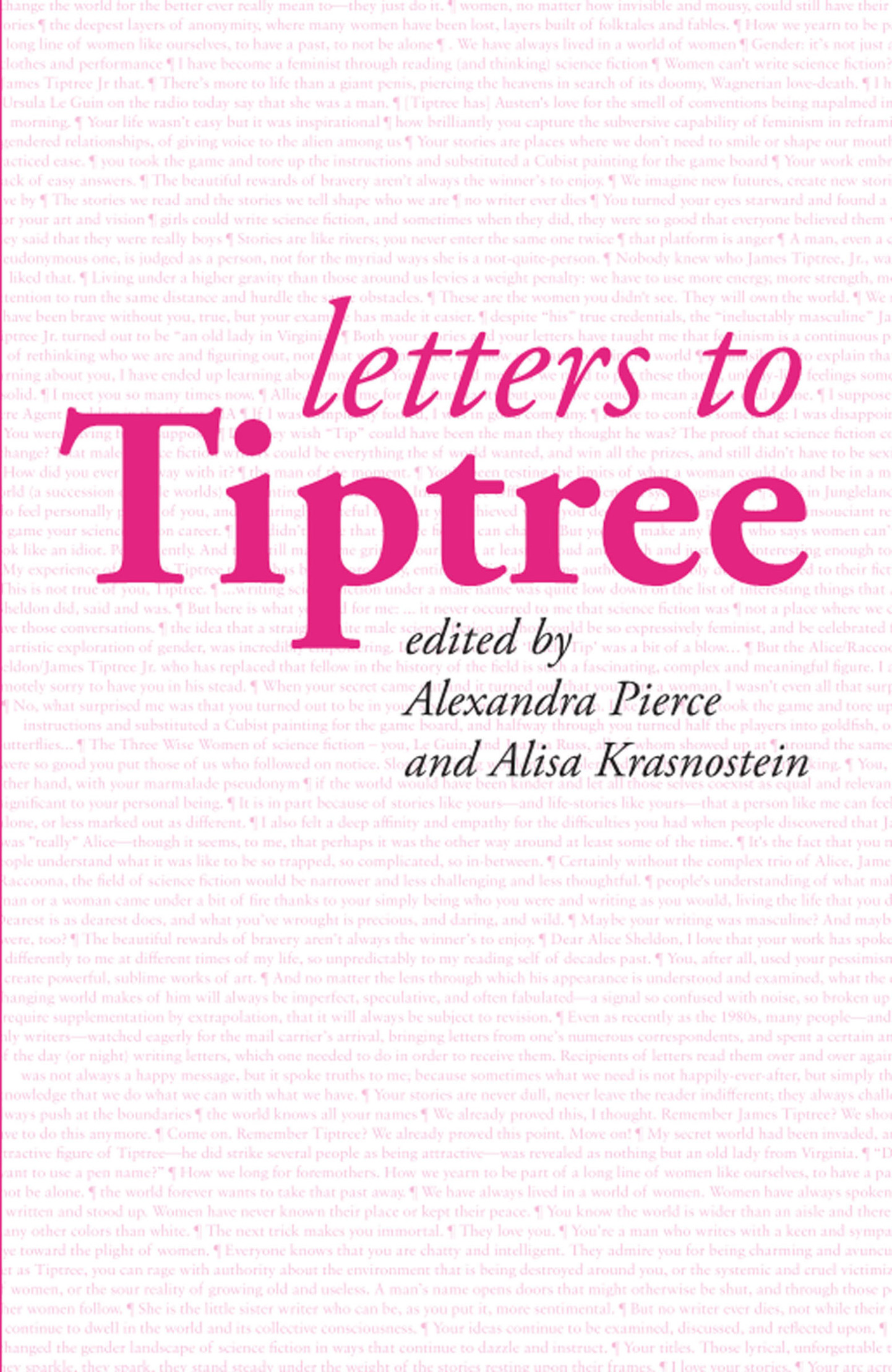

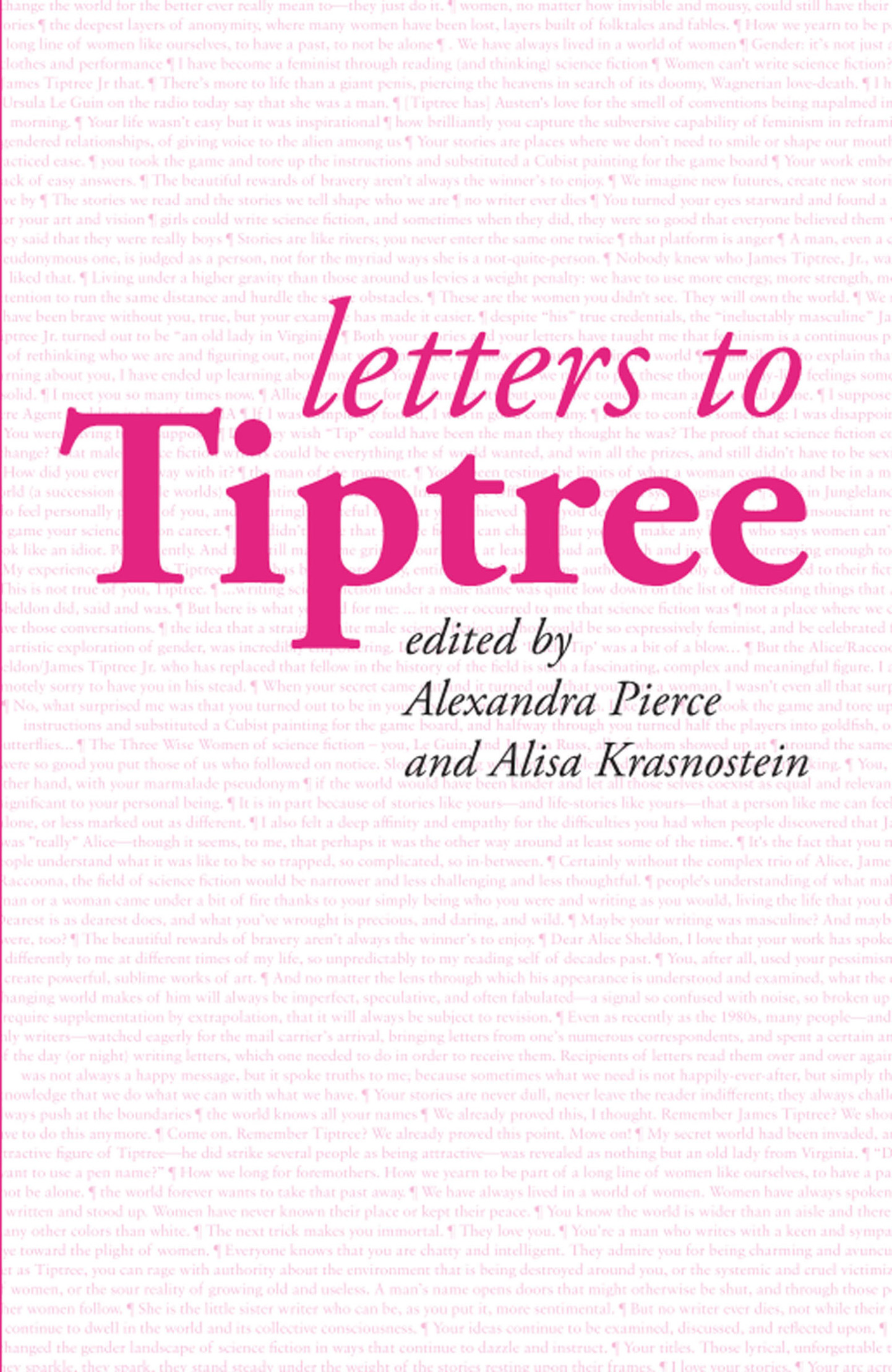

Letters to Tiptree

edited by Alexandra Pierce and Alisa Krasnostein

Letters to Tiptree

Published by Twelfth Planet Press at Smashwords

Copyright 2015 Alexandra Pierce & Alisa Krasnostein

http://www.twelfthplanetpress.com

Twitter: @12thPlanetPress

http://www.facebook.com/TwelfthPlanetPress

Sign up for the Twelfth Planet Press Newsletter

Introduction

In 1967, James Tiptree Jr. was born, named after a jar of marmalade in order to be forgettable to editors on rejection. His first fiction sale was in 1968 and 1969s The Last Flight of Doctor Ain caught the worlds attention. Ten years later, with two Hugo wins and three Nebulas under his belt, he, along with Raccoona Sheldon, was outed as Alice Sheldon, born in 1915, one aged suburban matron as she described herself. In Letters to Tiptree, we commemorate Alice Sheldon in her centennial year, celebrating her achievements and contributions as James Tiptree Jr.; remembering her amazing life outside of her writing career; and reflecting on her ongoing impact on the science fiction community, both in terms of her fiction and what it means to reflect on gender and identity.

We asked writers, editors, critics, and fans to write a letter to Alice Sheldon, James Tiptree Jr., or Raccoona Sheldon (or any combination thereof). We asked them to celebrate, to recognise, to reflect, and in some cases to finish conversations set aside nearly thirty years ago on Sheldons death. Were very pleased with the responses. Our letter-writers have engaged with specific storiesand which of Tiptree/Sheldons work has made the most impact will quickly become obvious. Others explored what it meant that a woman was behind James Tiptree Jr., and what that therefore means for other women who want to write science fiction. Still others have reflected on Sheldons gender and sexuality.

This book is presented in four parts. Section one, Alice, Alice, Do You Read?, is composed of letters written to Alice Sheldon, James Tiptree Jr., or Raccoona Sheldon (or all of them). The second section, I Never Wrote You Anything But The Exact Truth, presents selected letters exchanged between Sheldon and Ursula K. Le Guin, and Sheldon and Joanna Russ. Sheldon had had a long paper relationship with both women as Tiptree, and this continued well after the revelation of Tiptrees identity. We have chosen to include letters primarily from 1976 and 1977 that illuminate aspects of Sheldons identity and relationship with her two friends, as well as their reflections on Tiptree/Sheldon and his/her work. The letters have been reproduced with spelling mistakes and the occasional typewriter malfunction in place, to help preserve the sense of their immediacy and intimacy. We have included these exchanges partly because reading these letters is a wonderful privilegea glimpse into a passionate friendship always isand because we wanted to give Sheldon the opportunity to speak for herself and address some of the questions left unanswered. We especially wanted to know how (or whether) the revelation of Tiptrees persona changed the close relationships s/hed developed in the science fiction community.

In Everything But The Signature Is Me, we have reprinted academic material on Tiptrees work and identity. Ursula K. Le Guins introduction to Star Songs of an Old Primate, written soon after the revelation of Tiptrees identity, is an exploration of Tiptrees writing, as well as the question of his identity. Michael Swanwicks introduction to the 2004 reprint of Tiptrees 1990 collection, Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, provides further biographical detail on Sheldon for the unfamiliar as well as the experience of Tiptree being exposed as Sheldon. The excerpt from Justine Larbalestiers excellent The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction also examines Tiptrees identity and work, while Helen Merrick considers what makes something a tiptree text in light of the creation of the James Tiptree, Jr., Award. Wendy Pearson considers Tiptrees work within the context of reading the author as trans, and what it means for Sheldon to be Tiptree. Together, these pieces provide some context for understanding James Tiptree Jr., his work, and his relationship to/with Alice Sheldon. And, finally, Alice Sheldon herself writes about who she really is in the titular essay.

Editing this book together has been a remarkable experience. The honesty and enthusiasm evident in the modern letters has been startling and humbling. They inspired us to write our own letters to Tiptree, included in the afterword, Oh Joanna, Will I Have Any Friends Left? We also enjoyed the unexpected commentary on the act of writing a letter. Perhaps letter-writing is an art that needs to be revived. Additionally, the experience of reading the Sheldon/Le Guin and Sheldon/Russ correspondence was a remarkable and thought-provoking one. We are both intensely proud of the book that youre reading, and hope it will inspire and bring joy.

Alexandra and Alisa

August 2015.

Alice, Alice, Do You Read?

Dear Tiptree

They say a field, but really its a spaceport,

we cobbled it together out of dreams

we had assembled from popular mechanics

and broken hearts,

our yearning for stars, distance, escape,

for there to be something

out there,

something more,

cradles for spaceships patched up

from a carton of spark plugs.

There you came striding,

disguised

through our field, our spaceport,

looking as though you owned it,

swinging your new tool kit,

a wary awareness,

of edges of longing

your careful reflections,

your pulsing heart,

the honed lines of your craft.

You rocked our spaceport,

left it changed, wider,

more solid, more open,

stranger, expanded,

containing doors undreamed of,

marked men, women, other.

Now, each reaching out,

shall we walk forward

step into other

to see where it takes us?

Jo Walton

Neat Things

I thought a lot about that salutation, because the discovery that you were a woman changed my world when I was fourteen years old. But I first met you as a man, and so it seemed appropriate to address you that way. You were one of the kindly uncles and beloved teachers of my childhood, back when I was a gawky, confused girl in glasses too big for my face, reading everything that I could get my hands on, soaking it all in like a sponge.

I might have missed you if we hadnt been so poor. My reading material was often a decade or more out of date, dictated by what people with disposable incomes decided to get rid of. My mother, a connoisseur of yard sales and flea markets, came home one day with several boxes of back issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Thousands of short stories, novelettes, and novellas were suddenly dropped into my hands, and I read them all with the unthinking voracity of the starving bookworm. I didnt really keep track of authors, except to note whether the story was by a man or a womanand almost always, when it was the sort of thing I wanted to write someday, the sort of thing that spoke to me on a level so deep that it was difficult to put into words, the story was written by a man. I couldnt decide, at that age, whether women didnt write science fiction, or whether science fiction by women just didnt get published. At the same time, writing seemed like such a big, difficult,

Next page