Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

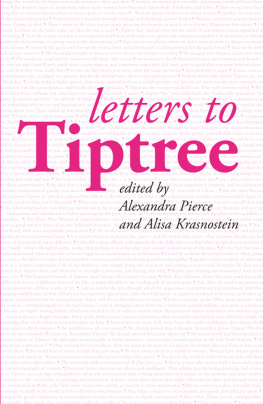

To learn to write at all, I had to begin by thinking of myself as a sort of fake man.

JOANNA RUSS TO JAMES TIPTREE, JR.

For Christs sake, Ruth, theyre aliens!

Im used to it

JAMES TIPTREE, JR., THE WOMEN MEN DONT SEE

No one [] has, to my knowledge, ever met Tiptree, ever seen him, ever talked with him on the phone. No one knows where he lives, what he looks like, what he does for a living. [] He volunteers no information about his personal life, and politely refuses to answer questions about it. [] Most SF people [] are wild to know who Tiptree really is.

GARDNER DOZOIS, 1976

In 1921 in the Belgian Congo, a six-year-old girl from Chicago with a pith helmet on her blond curls walks at the head of a line of native porters. Her mother walks next to her, holding a rifle and her daughters hand.

In 1929, the girl huddles under quilts in a cabin in the Great North Woods, reading Weird Tales. The candle by her bed flickers as an alien gently removes a young humans brassiere.

On Christmas Eve 1934, a nineteen-year-old in a white beaded evening gown makes her debut. At the party she meets a handsome, dark-haired boy in a tie and tails. She makes a joke; he laughs, and makes another. Five days later they elope and marry.

In 1942, a divorce wearing three-inch heels and a fox fur jacket goes down to a Chicago recruiting station and enlists in the army.

Sometime in the near future, a woman and a man meet an extraterrestrial exploring party. The man tries to protect the woman. The woman says she doesnt believe in womens chances on Earth, and asks the aliens to take her away.

In 1970, a man who does not exist sits down at a typewriter. He writes, At last I have what every child wants, a real secret life. Not an official secret, not a Q-clearance polygraph-enforced bite-the-capsule-when-they-get-you secret, nobody elses damn secret but MINE.

* * *

James Tiptree, Jr., appeared on the science fiction scene in the late 1960s, writing fast-paced, action-filled stories about rocket ships, alien sex, and intergalactic bureaucratic anxiety. He was a brilliant and original talent, with a voice like no one elses: knowing, intense, utterly convinced of its authority and the urgency of its message. No one had ever seen or spoken to the owner of this voice. He wrote letters, warm, frank, funny letters, to other writers, editors, and science fiction fans. His correspondence was intimate and revealing, yet even his closest friends knew little more about Tip than his address: a post office box in McLean, Virginia.

He was rumored to be a government official or secret agent. He did seem to know a lot about spooks around the water cooler: his characters worked in an unimportant bit of C.I.A. or remarked, Paranoia hasnt been useful in my business for years, but the habit is hard to break. He had opinions about fishing, duck hunting, and politics. He was courtly and flirtatious with women. When one of his friends, the writer Robert Silverberg, sent him a letter on his wifes stationery, Tip answered that he had shaved and applied lotion before reading on. Silverberg pictured Tip as a man of 50 or 55, I guess, possibly unmarried, fond of outdoor life, restless in his everyday existence, a man who has seen much of the world and understands it well. Men looked up to him. His women friends fell in love.

The stories that came out of PO Box 315 became more and more brilliant and disturbing. It wasnt the sex, and it wasnt the death, but it was the combination of the two. His stories read like urgent messages from some haunted house on the corner of Eros and Mortality. Humans meet aliensand abandon their very souls for a chance to sleep with them. A man in love with the Earth kills off the human race, including himself, to save her. A mission to the stars finds an alien egg for which the colonists themselves turn out to be the sperm.

Like Philip K. Dick, Tiptree used science fiction to talk about the importance of empathy and explore what it means to be humanthough he was less likely than Dick to question reality. Reality is there; the human project is to learn to see it, or die. Or learn to see ourselves: the reality of human flesh and emotions was what terrified, and fascinated, Tiptree. Can the body be trusted? Will it betray us? What does it want? Can we get rid of it?

This masculine writer, who let his readers in on the technology of space flight and the inner workings of government, also showed a surprising sympathy toward his female characters. He wrote about womens alienation in a world of men, and was held up as an example of a male feminist, a man who understood. Still, his stories were so full of action, abstract thought, and desire for women that everyone knew they were dealing with a man. In 1975, in an introduction to a book of Tiptrees short stories, Robert Silverberg wrote of his friend, It has been suggested that Tiptree is female, a theory that I find absurd, for there is to me something ineluctably masculine about Tiptrees writing.

He likened Tiptrees lean, muscular, supple stories to Hemingways:

Hemingway was a deeper and trickier writer than he pretended to be; so too with Tiptree, who conceals behind an aw-shucks artlessness an astonishing skill for shaping scenes and misdirecting readers into unexpected abysses of experience. And there is, too, that prevailing masculinity about both of themthat preoccupation with questions of courage, with absolute values, with the mysteries and passions of life and death as revealed by extreme physical tests, by pain and suffering and loss.

In the same year, another of Tiptrees letter-friends, the feminist science fiction writer Joanna Russ, wrote him that a professor at a party had asked me if you were a woman (!) by which I gather he cant recognize a female point of view if it bites him. When Tiptree participated in a written symposium on Women in Science Fiction as a token sensitive man, Russ told him he had ideas no woman could even think, or understand, let alone assent to.

By then Tiptree had introduced a protge, Raccoona Sheldon, who seemed strongly influenced by Tiptrees style. No one, not even herself, had opinions about Raccoonas sex: she was a former schoolteacher who published little and wrote, As for me, really the less said the better.

Tiptree did reveal a few facts about himself. He had been born in Chicago. His parents had been African explorers and his mother a writer. He had spent part of his childhood in colonial Africa, and the Second World War in a Pentagon sub-basement. He was reluctant to reveal his true identity because he couldnt have the people around him know he was writing science fiction, and because he liked his secret life.

Then in late 1976, Tiptree told a few friends that his elderly mother had died. More than one of Tips correspondents checked the Chicago papers and found an obituary for Mary Hastings Bradley, novelist, travel writer, and African explorer. Under survivors was listed her only child: Alice Bradley (Mrs. Huntington) Sheldon.

Ten years later, shortly before her death by suicide, Alli Sheldon wrote, My secret world had been invaded and the attractive figure of Tiptreehe did strike several people as attractivewas revealed as nothing but an old lady in Virginia.