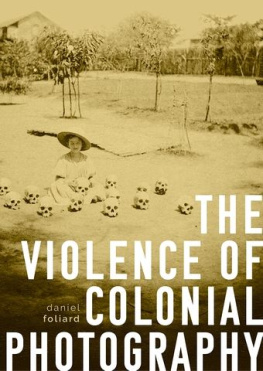

The violence of colonial photography

The violence of colonial photography

Daniel Foliard

Manchester University Press

Copyright ditions La Dcouverte 2020

The right of Daniel Foliard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by ditions La Dcouverte 2020

First English-language edition published in 2022 by Manchester University Press

Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

This work has benefited from a contribution from the ANR as part of the Programme dInvestissement dAvenir (ANR-17-EURE-0008)

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 6331 8 paperback

First published 2022

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Front cover image: Raymonde Bonnetain, Rene Bonnetain with the skulls of Samorys sofas Bibliothque Marguerite Durand, Paris

Cover Design: Fatima Jamadar

Typeset by

Cheshire Typesetting Ltd, Cuddington, Cheshire

Contents

.

.

At the Battle of Omdurman in Sudan in September 1898, the Anglo-Egyptian force under the command of Major-General Kitchener deployed and tested the very latest military technology against the numerically superior Mahdist forces under Abdullah al-Khalifa. As thousands of Mahdists launched a mass assault over open ground against the Anglo-Egyptian lines, they were met by a deadly hail of Lyddite shells launched from rapid-firing artillery, and expanding bullets fired from Maxim machineguns at a rate of 600 per minute. Altogether, Kitcheners troops expended more than 200,000 rifle rounds, and the Mahdists never made it closer than 1000 yards; an estimated 11,000 were killed and 16,000 wounded. The combined British and Egyptian forces suffered just 28 killed and 148 wounded.

Once the dust had settled, dozens of camera-wielding officers and correspondents dashed onto the battlefield to capture the effects of the carnage. Although it was paintings and engravings of the blatantly anachronistic charge of the 21st Lancers that came to dominate the public narrative, photos of the corpse-strewn battlefield of Omdurman were subsequently published in newspapers, magazines, and memoirs. The fact that wounded Mahdists had been left to die, and that Kitchener was rumoured to have disinterred the Mahdis body and kept the skull as a trophy, initially caused a minor scandal back in London. Yet the criticism never amounted to much during an age when it was generally accepted that this level of violence was a necessary feature of colonial warfare as was its photographic documentation. By the end of the nineteenth century, as Daniel Foliard argues in this important book, the camera had become an essential part of the colonial toolkit and the photograph the paramount trophy of imperialism.

The grainy images from Omdurman represent just a few examples of the thousands of photos that were produced during the Scramble for Africa and relentless Western imperial conquests around the world in the decades around 1900. Apart from the aftermath of battles and massacres, this well-established repertoire included scenes of punishment and executions, as well as portraits of captured rebels and other prisoners. Taken by professionals and amateurs alike, some of these images were carefully staged tableaus, emulating the composition and conventions of formal paintings. Others were blurry snapshots captured in the spur of the moment. The visual economy of colonial photography was underwritten by the same double-standards of the imperial project more broadly: the racialised logic that required the unlimited use of force against so-called savages also justified photographing their dead and dying in ways that would have been unthinkable in conflicts between civilised people. Photography thus produced colonial violence as a spectacle to be consumed back home in the imperial metropoles.

The Violence of Colonial Photography is a brutally honest and radically innovative history of British and French imperialism, one that is entirely shorn of exceptionalist bluster and the euphemisms of the savage wars of peace. Foliard traces the trans-imperial and global trajectories of photographers and their photographs across multiple conflicts both famous and forgotten throughout Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. With more than eighty photos, extracted from an ocean of images, and based on extensive research in public and private collections, this is a genuine work of historical excavation literally and figuratively. In some of the books most powerful sections, Foliard examines lost images: photographs described in contemporary sources but which no longer exist. The sense of historical erasure is palpable, yet in order to salvage something of this lost visual world, and to recover what photography might have meant to its authors and its audiences more than a century ago, Foliard relies on the written word as much as the image. The two, we are reminded, were always co-constitutive.

Despite the popular notion that photos somehow speak for themselves or are worth a thousand words, images of colonial violence were never self-explanatory and the stories they told never uncontested. What determined the meaning and significance of a photo was not simply what it depicted as much as the way its subject was depicted, as well as the manner in which it was framed, captioned, and presented for different audiences. Just as a hunt would not be the same without a trophy, so too would the defeat of indigenous people not be the same without a photo of colonial soldiers posing with the bodies of their slain enemies. Depending on the specific circumstances, however, such an image could be a dirty secret shared only with fellow veterans of colonial wars, or it could be proudly displayed on the mantelpiece in the gentlemans smoking room. It might even be published in a newspaper to celebrate colonial heroism or, conversely, it could end up as evidence of atrocity and deployed in the cause of anti-imperialism. This is why, Foliard asserts, colonial photography cannot simply be examined as a two-dimensional image on a piece of paper but must be understood as an act and as an ongoing process.

The book furthermore offers a rare glimpse into the private world of European officers and soldiers who used photo albums to curate their memories and craft personal narratives of their experiences on the colonial battlefields of the time. Commercial postcards of landscapes and local women, equally exoticised, were imbued with personal significance when inserted among private snapshots at times even inscribed with personal notes, thus turning stock images into intimate souvenirs. Deeply attentive to the materiality of photographs, Foliard reveals the ways in which the significance of images changed as they circulated locally and globally, between periphery and metropole, and between the public and the private. As assemblages of personal memories, the content of colonial photo albums is both shocking and deeply illuminating: images of domestic bliss (settler-style), with European children playing with their native servants, can thus be found right next to horrific photos of death and destruction. As the books cover shows, these seemingly incompatible scenes were sometimes combined within the very same photo a visceral testament to the normalcy of extreme violence as a ubiquitous feature of Western imperialism at the dawn of the twentieth century.