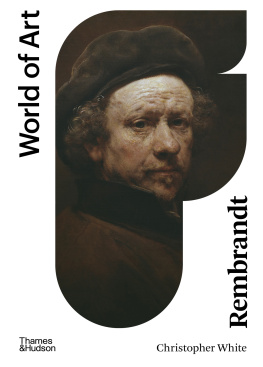

Rembrandts Jews

STEVEN NADLER

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago & London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd. London

2003 by Steven Nadler

All rights reserved. Published 2003

Paperback edition 2004

Printed in the United States of America

13 14 15 16 17 10 9 8 7 6

ISBN: 0-226-56736-2 (cloth)

ISBN: 0-226-56737-0 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-226-36061-4 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nadler, Steven M., 1958

Rembrandts Jews / Steven Nadler.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-226-56736-2 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, 16061669Relations with Jews. 2. JewsNetherlandsAmsterdamHistory17th century. 3. Jews in art. I. Title.

N6953 .R4 N33 2003

759 .9492dc21

2003004088

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

FOR

CLARA NADLER  and SOPHIA HERTZ

and SOPHIA HERTZ

Contents

Illustrations

BLACK AND WHITE

COLOR GALLERY

Acknowledgments

I am extraordinarily grateful to a number of people for the help they provided me as I worked on this book. Robert Bernstein, Miriam Bodian, Marc Kornblatt, Tim Osswald, Bella Pomer, Shifra Sharlin, Larry Silver, David Sorkin, and Red Watson all read early drafts and offered extensive and valuable suggestions for improvement. Mirjam Alexander-Knotter and her colleagues graciously shared with me the results of their research into Jewish art patronage in seventeenth-century Amsterdam. I especially want to express my gratitude to Shelley Perlove and Michael Zell, who took time away from their own research into Rembrandt and seventeenth-century Dutch art to go through the manuscript and make important corrections and useful comments; I appreciate their generosity, not to mention their forbearance with an art history amateur. In Amsterdam, Henriette Reerink proved herself to be, once again, a true and patient friend; and I am indebted to the curators of the Museum het Rembrandthuis for allowing me to view the renovated house in the off hours. At the University of Chicago Press, I thank Alan Thomas and Susan Bielstein, whose enthusiasm and encouragement for this project are just what an author needs; I also appreciate the help of Anthony Burton and Drusilla Moorhouse. And finally, all my love, as ever, to Jane, Rose, and Ben.

On the Breestraat

ONE

IT IS THE SUMMER OF 1653, midweek in early August. The afternoon is warm and humid, as these months tend to be in Amsterdam, even in this century of intensely cold winters. There is a bustle on the avenue along the canal called the Houtgracht, where the floral and vegetable markets overflow with shoppers trying to complete their daily errands. Some people congregate in small groups to catch up on local gossip or trade rumors about the war with England, where things are not going well for the Dutch. Off to the side, just before the little drawbridge over the canal, a number of well-dressed men conversing in Portuguese file into a house. They gather to conclude a deal or settle some pressing legal matter. A few doors down, children tumble out of a school. They run helter-skelter over the cobblestones and skip stones across the canal. A shout goes up whenever a stone reaches the other side.

One must wait to cross the canal. After a masted boat has passed through, the drawbridge comes down very slowly. On the other side of the narrow waterway, the street continues straight ahead, where more flower stalls offer fragrant enticements. Just one block down is Sint-AnthonisbreestraatSaint Anthonys Broad Street. A neat row of houses, all with similar redbrick facades and steeply pitched gables, lines each side of the street. Breestraat, as it is called, is wider than the thoroughfare that leads over the canal, with more pedestrians, horse-drawn carts, and well-apportioned carriages stationed in front of houses. To walk safely down the street at this time of day, one must stay close to the side and out of the way of the traffic.

At the end of the block, on the corner on the left and just back from the row of trees that line the lock on the canal, stand two large houses. Like many of the other dwellings, they are attached to each other by a common wall. The second house from the corner, the left one of the pair, is No. 4; it is the home of a prominent painter of portraits and histories.

It is an impressive housenot a true mansion, like the one Isaac de Pinto built for himself across the street, but even so it is a stately place. The three-story facade is made of brick with inlaid stone. It is quite wide, thirty-two feet across. Its tall front windows are topped by half-moon arcs of brick and stone. Above the roofline rise two thin dormer windows, each with a beam and pulley-hook sticking straight out into the street. The only way to move things to the upper floors of these narrow Dutch houses is to hoist them up and through the windows. In the center above the uppermost row of windows, crowning it all, is a decorative stone relief.

There is a tumult in front of the two houses. The street has been turned into a construction site. Building materials are strewn aboutlumber, bricks, sand, mortarand workers tramp in and out of both homes. Most of the work is going on in No. 2, on the right, the corner house, but repairs are also being made to the foundation of its companion.

Two wide steps lead up the stoop of No. 4. The front door, its threshold caked with dried mud, is propped open. The house is filthy. There is dust everywhere: plaster dust, sand dust, dust from the stones, and dust from the wood. It comes floating in from the worksite on the street through the open windows. It is tracked in on shoes and it falls off the shaken walls. Dust covers the floors and carpets, the windowsills, the sheets on the bed, the table, the food. Dust coats every surface of the house. It is even in the studio, complains the owner. The bare canvases are covered by a thin layer, enough to interfere with their priming; all of them will need to be cleaned. The paintings that were still wetworks in progress and recently finished piecesare ruined. The dust that worked its way onto them is there for good. It is of no use to sweep up at the end of the day, he complains; by the time the air settles in the night, everything is covered again. The place is a goddamn mess, he sighs, and there is no end in sight.

Then there is the rattling. The house shakes with every swing of a sledgehammer, with each attempt to ram a beam into place; the windows chatter every time a nail is driven into lumber, and whenever a new brick is tapped into line. The construction required in No. 4 is in the basement, but it makes the upper floors reverberate. There is no escaping the tremors. They reach right down into a mans soul.

Worst of all is the noise: the incessant banging and cutting and hammering and chopping and knocking, the shouting and the yelling, the sharp cracking sound of wood thrown on top of wood, and the ringing of stones tossed from a wagon onto the street. It is enough to drive one mad.

...

It took the contractor Pieter Swense six monthssix bone-jarring, nerve-shattering monthsto jack up the house of Rembrandts neighbor in No. 2 Breestraat, the Jewish merchant Daniel Pinto. The house had to be raised by three feet and two thumbs (about eighty-six centimeters). One reason the project took so long was the shortened workweek. The Dutch contractor and his men certainly would not have worked on Sunday, Gods day; and Pinto must have stipulated that they could not labor between sundown Friday and sundown Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, either. There may have been other factors, too. In addition to paying Swense thirty-three guilders, Pinto agreed to throw in half a keg of good quality beer [that can be] consumed on the job. This was presumably a daily ration. The workmen were free to imbibe more frequently if they wished, but it is explicitly stated in the agreement that this additional refreshment will be at the expense of the contractor. As the days grew warm, half a keg of beer would not have gone very far.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. and SOPHIA HERTZ

and SOPHIA HERTZ