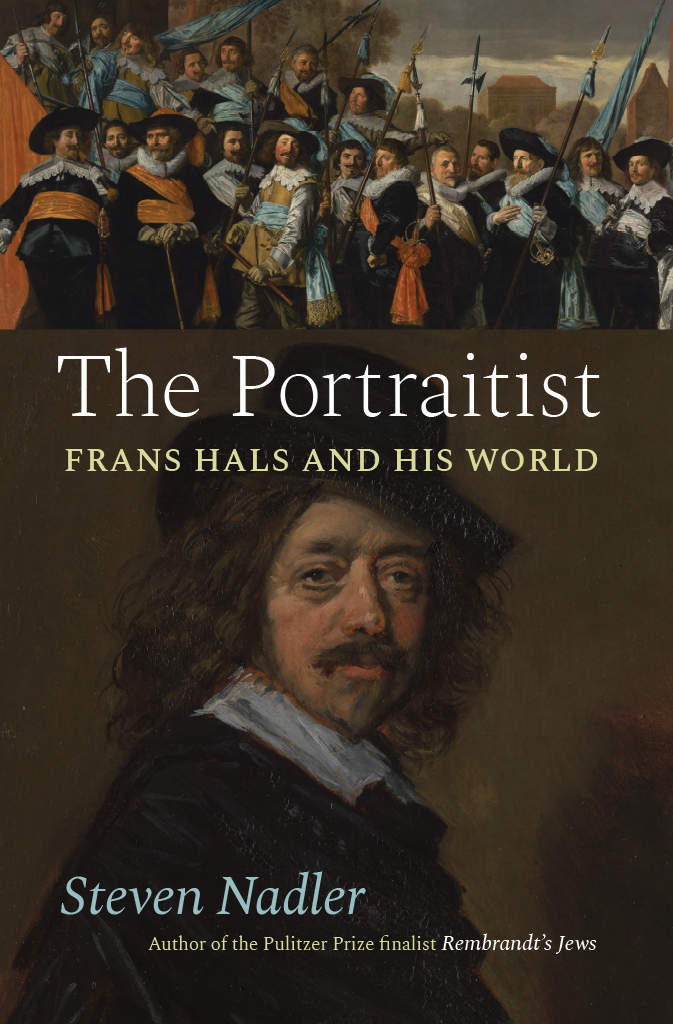

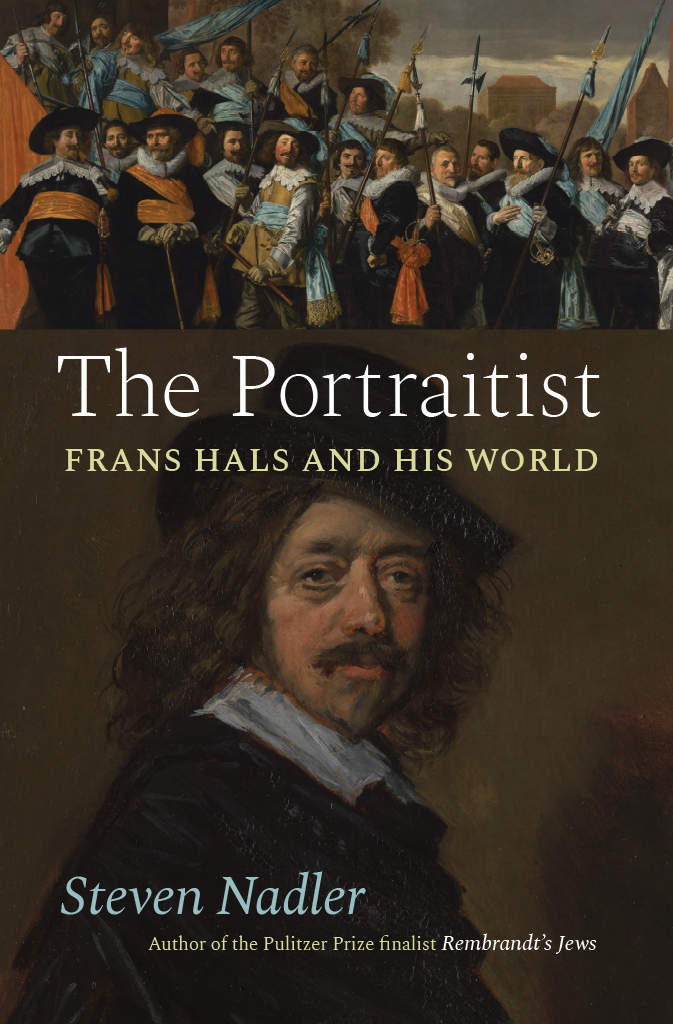

The Portraitist

The Portraitist

Frans Hals and His World

Steven Nadler

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2022 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-69836-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-69853-3 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226698533.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nadler, Steven M., 1958 author.

Title: The portraitist : Frans Hals and his world / Steven Nadler.

Other titles: Frans Hals and his world

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021057670 | ISBN 9780226698366 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226698533 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hals, Frans, 15841666. | PaintersNetherlandsBiography. | Portrait paintersNetherlandsBiography. | NetherlandsHistory17th century. | Haarlem (Netherlands)History17th century. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC ND653.H2 N33 2022 | DDC 759.9492 [B]dc23/eng/20220112

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021057670

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

[Portraiture is] that branch of art that is the wondrous compendium of the whole mannot only mans outward appearance but in my opinion his mind as well.

Constantijn Huygens, 1630

Contents

All works are by Frans Hals unless otherwise indicated.

Figures

Plates

A deal is a deal, or so thought the officers of the Saint George civic guard company of Amsterdams District 11. They wanted a portrait of themselves to commemorate their service to the city, as was customary. It had to be dignified, reflecting their virtues as brave and responsible citizens, but without being stuffy and formal, like the old civic guard portraits. In those earlier group paintings, everyone appeared in the same stiff pose, and they all looked so much alike it was hard to tell one person from another. No, these leading men of the great city of Amsterdam wanted something lively and colorful to hang in their headquarterssomething modern.

Ordinarily, Amsterdam civic guards hired Amsterdam painters for such an important commission. The Saint George officers, however, broke with tradition. They went beyond the city limits and sought out a celebrated master painter from Haarlem. The terms of the agreement were clear: the artist was to come to Amsterdam on a regular basis, and the sixteen guardsmen would take turns posing for him in a borrowed studio. He was to be paid sixty guilders per figure.

Everything should have gone smoothly. Travel from Haarlem to Amsterdam was relatively easy now that there was a canal between the two cities. The painter could take a barge or go by land along the tow path. Overnight stays in Amsterdam would be necessary, but not too much of an inconvenience. Moreover, this was an experienced painter of civic guard portraits; he had already completed three of them for Haarlem companies and was about to start work on his fourth. He could give the Amsterdam militiamen just what they were looking for, since what they were looking for was just what they had seen in his paintings.

In the end, though, it did not work out well. Things took a bad turn when, after a number of sessions in Amsterdam and making good progress on the large canvas, the painter suddenly stopped coming to the city. He refused to leave his Haarlem home and studio. It was too much trouble, he complained, and his lodgings in Amsterdam were costing him a lot of money for which he was not getting reimbursed. If they wanted the painting finished, they would have to come to him.

That was certainly not the arrangement, the officers argued as they filed the first of several legal complaints against him. He could not possibly expect all of them to travel to Haarlem. Come to Amsterdam and finish the painting, they demanded, or they would have another artist finish it. Still hopeful that they could persuade the painter to resume his work, they sweetened the pot and offered him an additional six guilders per figure.

By 1637, four years after the commission, negotiations had broken down completely. Much to the dismay of the Amsterdam guardsmen, Frans Hals would not budge. He was leaving more than a thousand guilders on the table, a significant amount of money for any seventeenth-century artist but especially for a man with financial problems. But he could not afford to be away from Haarlem so often, or so he saidhe had apprentices to supervise, other projects to attend to, and a family to care for. He called their bluff. Let someone else finish the damn painting.

It was not the first time that a brilliant but stubborn and irascible artist had aggravated a clientMichelangelo famously caused splitting headaches for the popes he served (and vice versa)nor would it be the last; Rembrandt, a contemporary of Hals, was a difficult character, and Picasso was best avoided when he was in one of his moods. We do not know how typical such behavior was for Hals. But one thing is certain: never again would a commission from an Amsterdam civic guard company come his way.

*

This book offers a portrait of one of the greatest portrait painters in history. The name of Frans Hals may not be as familiar as other marquee names of early modern art, especially the outstanding portraitists of the seventeenth century: Velzquez, Rubens, Van Dyck, and Rembrandt. And yet, those who have seen Halss work in museums or in art history books will immediately recognize his style. Whether or not they know of Hals, they know Halsthat rough, loose brushwork, not unlike what we find in later Impressionist paintings, that when viewed up close seems like nothing but abstract daubings, but when seen from a distance so beautifully captures the well-to-do citizens of the Dutch Golden Age.

It is a style like none other in the period. Rembrandt, of course, put his own mark on portraiture with a painterly manner that grew coarser over the years. One contemporary criticthe painter Gerard de Lairesse, whose portrait Rembrandt did late in his own lifecomplained that the paint in Rembrandts works runs down the piece like shit [drek]. Hals and Rembrandt were likely working side by side in the same Amsterdam workshop for a brief time, and no doubt Rembrandt was impressed by what Hals, his elder by almost twenty years, was doing with paint on his panels and canvases. But there is no mistaking a Hals for a Rembrandt. Hals may have painted in what was by then a well-established tradition, but he had an approach to rendering sitters that was all his own.

Over the course of a long career, more than fifty years as a master konstschilder (fine art painter),sought him out for portraits that they could proudly hang on the walls of their homes and boardrooms and impress visitors with their cultivated taste. To his contemporaries, in Haarlem and beyond, Hals was, for several decades at least, the modern painter par excellence.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).