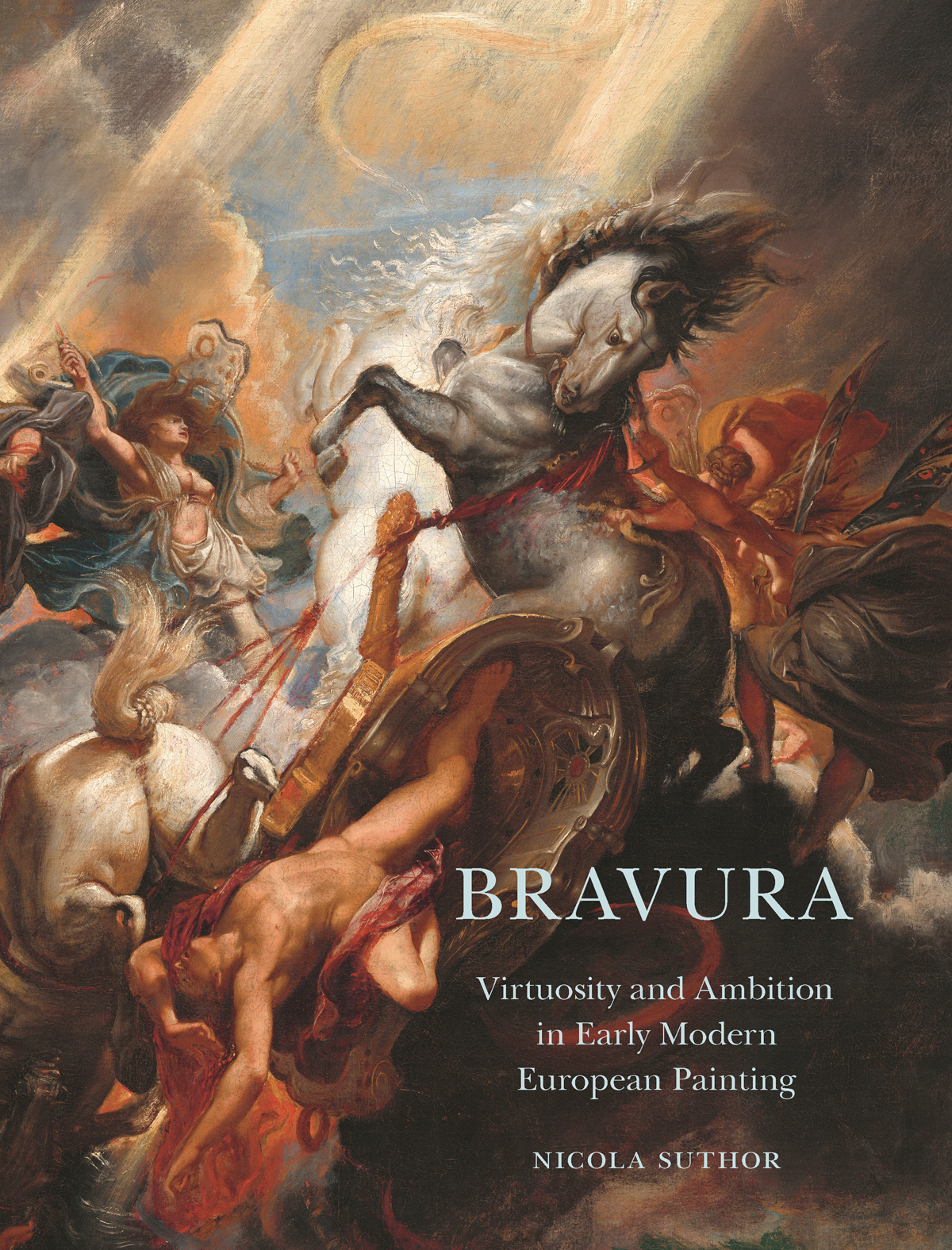

BRAVURA

Virtuosity and Ambition

in Early Modern

European Painting

NICOLA SUTHOR

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2021 by Nicola Suthor

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Front cover: Peter Paul Rubens, The Fall of Phaeton (detail), ca. 16041605.

Oil on canvas, 98.4 131.2 cm. National Gallery, Washington, DC.

Back cover: Jean-Honor Fragonard, Abb Claude Richard de Saint-Non, 1769.

Oil on canvas, 80 65 cm. Muse du Louvre, Paris.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-20458-1

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-691-21343-9

Version 1.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020946307

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Published in part with the generous support of the Publications Fund of the Department of the History of Art, Yale University.

Designed by Julie Fry

Contents

BRAVURA

Introduction

Because someone mentioned [to Giuseppe Cesari] one day that Annibale [Carracci] had spoken ill of one of his works, when [Cesari] then happened to meet him, he wanted to take his sword in hand and fight. But Annibale, who knew the only true bravado between them should be that of painting and not of dueling, took up a brush and showing it to him, said: It is with these weapons I challenge you and confront you; and thus he was truly assured of achieving an advantage over his enemy.

ANDR FLIBIEN

Ars est ostendere artem, or art is to demonstrate art, is the rhetorical message of a painterly style known as bravura that emerged in sixteenth-century Venice and spread throughout Europe over the course of the seventeenth century. An anti-academic attitude, bravura subverted the formerly regnant dictum Ars est celare artem (true art is to conceal art), which claims the illusion of transparency as the ultimate goal of painterly mimesis. In this earlier paradigm, art acquired prestige by distancing itself from the practical aspects of painting as craft, and in doing so generated a disparity between effect and matter. An exclusive focus on the artworks true to life quality created a concept of the image that accentuated the natural appearance of pictorial illusion by eclipsing its artifice. The goal of art in this case the evocation of an image in the beholders imagination guided a self-effacement of the artist and subjugated the creative process to the higher purpose of pure illusion. While celare only makes sense if ars has a double significance (the art that is concealed cannot be the same as the art that conceals), ostendere is the affirmative emphasis of a seemingly one-dimensional concept of art. The artist operating in the latter modus accomplishes their ascent to art by successfully manipulating painting materials and techniques. The ostentatious demonstration of manual and technical skill becomes the higher purpose of the artworks execution, a purpose that is by implication performative.

The maxim learning by doing comes to mind an idiomatic expression that can be traced to Aristotle (384322 bce ): We learn an art or craft by doing the things that we shall have to do when we have learned it: for instance, men become builders by building houses, harpers by playing on the harp. Similarly we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts. However, the ancient philosopher follows his admission by denigrating the inferior wisdom such empiricism represents a rejection that would prove decisive for Early Modern art-theoretical discourse, which privileged theory over practice and thus posed the perfect foil for the spectacle of bravura.

To a substantial degree, this discourse centered on the controversial issue of artistic practice. The painter Vicente Carducho (15761638), a native of Florence who lived most of his life in Spain, took up Aristotles distinguishing criterion in his Dilogos (1633) to belittle popular acclaim for a way of painting known as alla pratica: As for those that make such paintings of simple imitation, I regard them to be like empiricist doctors, who without knowing the cause are able to work wonders; they certainly garner great applause before the tribunal of the senses and their works elicit amazement, sometimes deceiving the sense of sight with their evocative imitation; and I do not doubt that all those who serve on this tribunal raise their voices and cheer, although here Reason and Discernment do not dare participate. What wins popular applause is, Carducho alleges, the opacity of a practice that appears to produce miraculous results.

Carduchos criticism places him in a long line of authors in art literature who have attempted to shed light on ars as a subject shrouded in mystery. The painter and writer Giovanni Battista Armenini, in his collection of painting precepts titled De veri precetti della pittura (1578), explicitly denounces the bad habit (abuso) of excellent masters of our time (i maestri eccellenti de nostri tempi) who when they are working lock themselves away and close up every crack, so that their assistants cannot see them.

La grandezza e oscurit dellarte, which Armenini wished to illuminate in his book, also fascinated the painter and theorist Gian Paolo Lomazzo, who literally did go blind early in his life. In his Idea del tempio della pittura (1590), he affirms: Because painting is such a difficult and recondite art, there is no mind in this world that, considering engagement with it, would not become confused and terrified. His insistence on the empirical derivation of his assembled knowledge is paradoxical, however, for he ultimately expects the reader to adopt his principles as the foundation for their own investigation of the subject, thus elevating his personal erudition to the level of the generalizable.

What motivated a number of similar treatises in this epoch was the desire that painting be recognized as a higher art according to Aristotles definition: noble artistic pursuits spring from a prerequisite awareness of causation, a realization superior to and distinguishable from mere experience, no matter how successful experience may be at achieving a specific end.

This debate was founded on a nuanced understanding of the specificity of artistic knowledge. The humanist Benedetto Varchi (15021565), whose conception of art relied heavily on Aristotle, drew a sharp distinction between art and science in a famous address delivered to the Florentine Academy in 1547 and published in 1550. He identified two types of reason: particular and universal, the first being a cognitive power (cognitiva) fundamental to the discrete intention that aims at the manufacture of objects, while the second is exclusively involved in the formation of general concepts. Varchi admits that in the arts there is more need for consultation and discussion than in science; however, such consultation does not concern an ultimate purpose but rather the possible means to achieve it. In the visual arts, therefore, it is not the speculative and contemplative, but rather the practical and active modes of the mind that open up the field of creative possibility, in the sense of determining what is actually doable (