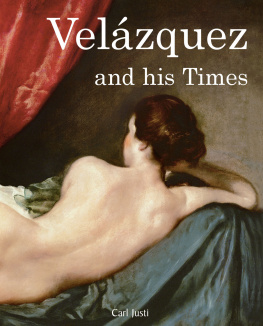

Text: Carl Justi

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-756-8

Publishers Note

Out of respect for the authors original work, this text has not been updated, particularly regarding changes to the attribution and dates of the works.

Carl Justi

VELZQUEZ

and his Times

CONTENTS

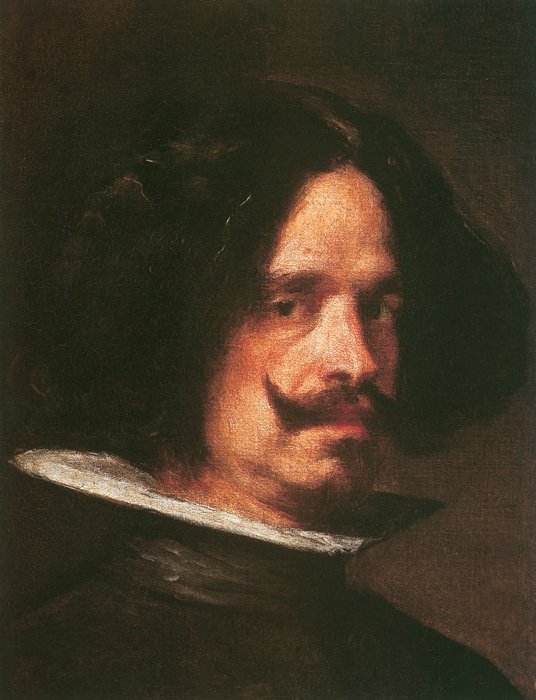

1. Self-Portrait, c.1640.

Oil on canvas, 45.8 x 38 cm.

Museo de Bellas Artes de San Pio V, Valencia.

Introduction

Up until the late eighteenth century the name of Diego Velzquez was still very rarely known in most parts of Western Europe. The muster roll of the great painters seemed long closed, and no-one suspected that in the far west, in the palaces of Madrid and Buen Retiro, lay concealed the works of an artist who possessed a full claim to rank with the foremost of the great masters. It was thanks to a German painter named Raphael Mengs that Velzquez obtained his place in art history. Describing Velzquezs works as using a natural style, Mengs discovered him superior even to those whom he had hitherto regarded as the leaders in that field, artists such as Titian, Rembrandt, and Gerrit Dou.

The best models of the natural style, Mengs wrote in 1776 to Antonio Ponz, the leader of Spanish art, are the works of Diego Velzquez, in their knowledge of light and shade, in the play of aerial effect, which are the most important features of this style because they give a reflection of the truth. Velzquez is one of those individuals that brook no comparison with any others. All attempts to sum up such a person in a single sentence end only in platitudes or hyperbole. The Court painter of Charles III regarded him as the first of the naturalists. Piety and mysticism have been mentioned as the peculiar and dominant characteristics of Spanish art, and this may be true of its subject matter as well as of the strict religiosity of its exponents.

Spain has her solitary Murillo, whose intellectual calibre is comparable to that of devotional painters such as Guido, Carlo Dolce and Sassoferrato, but what places Velzquez far above these is the happy association of homely national types, local colouring and play of light seen through his naturalism and genial childlike character. What fascinates strangers about the Spanish religious paintings is not so much their wealth of feeling and depth of symbolism as a certain touch of earnestness, simplicity and downright honesty.

These artists were far from making religious subjects a pretext for introducing charming motives of a different order, but with medieval artlessness they never hesitated to transfer such subjects to a Spanish environment. In the fifteenth century we find the retablo painters of the provincial schools, under the influence of the Flemings, already showing similar tendencies, even within the narrow bounds of Gothic art. But the intruding Italian spirit soon arrested these beginnings of a genuine national school. For an entire century the Spaniards devoted themselves to idealism with the result that, for all their pains, they produced nothing but indifferent works.

Then followed the reaction in the opposite system but now with very different artistic powers. The invariable effect of this system was to give scope to individuality, pointing as it did to Nature as the true source of inspiration, and placing talent on an independent footing. But these very Spanish masters, of a pure and even rugged type, became known throughout the world and created the idea of what is called the Spanish School. Of this group, Velzquez was the most consistent in principle; he possessed the greatest technical skill, and the truest painters eye. Hence, from the material standpoint, he may be accepted not only as the one almost purely secular Spanish painter, but the most Spanish of the Spanish painters.

Velzquez was often attracted by what was difficult to grasp and reproduce, but what at the same time was of daily occurrence, familiar as sunlight itself. Few others have given less free rein to the play of fancy, or turned to such little account the opportunities of immortalising beauty, and few also have shown less sympathy with the yearning of human nature for that unreal which consoles us in the realities of life. But his portraits, landscapes and hunting scenes, all that he ever did, may be taken as standards by which to measure the depth of the conventional in others. The medium though which he viewed Nature absorbed, to use a physical illustration, fewer colour elements than that of other artists. Compared with Velzquez, Titians colouring seems conventional, Rembrandt fantastic, and Rubens infected with a dash of unnatural mannerism. Whatever Velzquez saw he transferred to the canvas by methods of a constantly varying and even impromptu character, which are often a puzzle to painters. He impresses the great majority of those who handle the brush, especially by the outward display of those expedients, as the most ingenious of all artists, that is, one who can make the most out of the slenderest resources, and we often forget that for him this is merely a means to the end. Hence the never-failing attraction possessed by Velzquez works. The lifelike charm that they exercise lies both in their outward and inward aspects, in the glow of the complexion and the revelation of the will, in the breathing, throbbing glance and the depth of character. Compared with the colourists of the Venetian and Dutch schools, Velzquez appears even prosaic and jejune; and we scarcely know an artist with fewer attractions for the uninitiated. In each individual work he is new and special, both as regards invention and technique. The interest and enthusiasm with which we contemplate art works of the past would appear to depend not only on a yearning after historic knowledge or on the practical utility of such studies; it must also be somewhat independent of our attitude in the idle discussion about the superiority of old or modern art.

Painters declare that, in regard to technique, they have nothing more to learn from the old masters. The times of Cervantes and Murillo in Spain, when special forms were created for special material, conditions and ways of thought, may also be taken as a special, if somewhat limited, phase of humanity, entitled to a niche in its pantheon, and not merely to a page in the records of historical finds. The Museo Pictorio was the only source of information regarding Velzquez and his associates outside Spain down to the twentieth century. The account of Velzquez life contained in it was translated into English in 1739, into French in 1749, and into German (in Dresden) in 1781. DArgenvilles Biography (1745) is a mere summary of this account. Antonio Ponz introduced a few descriptions of paintings into his

Next page