Julia Blackburn

OLD MAN GOYA

Julia Blackburn is the author of three books of nonfiction, Charles Waterton, The Emperors Last Island, and Daisy Bates in the Desert, and of two novels, The Book of Color and The Lepers Companions, both of which were shortlisted for the Orange Prize. She lives in England.

ALSO BY JULIA BLACKBURN

Charles Waterton

The Emperors Last Island

Daisy Bates in the Desert

The Book of Color

The Lepers Companions

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, JULY 2003

Copyright2002 by Julia Blackburn

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Random House U.K., London, in 2002.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Pantheon edition as follows:

Blackburn, Julia.

Old man Goya / Julia Blackburn.1st American ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Goya, Francisco, 17461828Last years.

2. ArtistsSpainBiography. I. Title.

N7113.G68 B57 2002

760.092Bdc21

2002280534

eISBN: 978-0-307-82920-7

Author photograph Jerry Bauer

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

In memory of my mother

Rosalie de Meric (19161999)

Contents

He knows neither what he wishes for, nor what he can hope for. He is celebrated for his restlessness, his angers, his passions; he is full of curiosity; he frequents fairs and popular ftes, taking a lively interest in circus animals, acrobats and monsters. He paints, draws, engraves, learns lithography and initiates himself in all the technical discoveries. His lucidity is absolute.

(Goya at the age of seventy-nine)

1

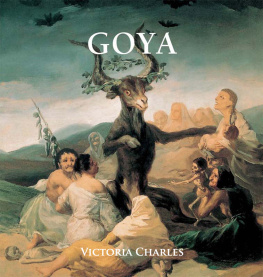

I have been busy with Goya for many years. When I was a child there was a paperback edition of his etchings, tucked small and unobtrusive in the bookcase in my mothers painting studio. The white spine of the book had been broken and partially torn away, exposing the intimacy of the stitches that bound the pages together.

On the cover a young woman sat on a low stool and challenged me or any other stranger with an unblinking gaze. Her long hair was being brushed by a smiling woman who was almost concealed in the shadows, while a third woman, terrifying and ancient and dressed in white robes, was crouched on the floor like a heap of pale stones, turning the beads on her rosary and the dangerous thoughts in her head.

The artists signature, Fran de Goya, appeared underneath the picture, printed in a bright red that looked to me like fresh blood, the final a twirling its tail downwards with the wild energy of a spinning top.

I used to steal this book from its shelf and take it quietly to my room. I would stare at the cover and try to understand what secret things had just happened and were about to happen here. I would open the pages at random so that the other dark and interrupted stories could play before my eyes. People becoming animals and animals becoming people. Masks to hide a face and faces turning into masks. Leathery old skin next to soft young skin and a thick blackness on all sides out of which monsters could emerge like rabbits pouring in an endless stream from a magicians hat. I was terrified by what I saw and yet I felt brave and somehow invincible because I had dared to look at it.

I have the same book lying on the table beside me now. It is more battered than before. The broken spine is held together by strips of Sellotape that have become dry and brittle. A blot of ink has fallen in a little explosion on the delicate fabric of the seated womans dress. A corner of the cover is missing. But when I turn the pages the shivering intensity of those images is as sharp as ever and as vivid as memory itself.

So that is the first root of my connection with Goya. He seemed to belong to me like a member of my own family, distant, but sharing the same blood. For a long time he sat quietly in the back of my mind, stirring occasionally, but not making any demands until the day when I went to the Prado Museum in Madrid and entered the two big rooms that hold his so-called Black Paintings. It was the noise of them that struck me first: an echoing reverberation of savage human voices all competing with each other and demanding to be heard. It was only later that I began to notice the silences as well, the great pools of silence that were every bit as powerful as the noise.

The person standing next to me explained that Goya was deaf when he made these pictures; he was stone deaf from the age of forty-seven until he died at the age of eighty-two. And that was when I decided I wanted to find out more. I wanted to know what sort of world this deaf man had inhabited and how he had managed to live with the isolation of deafness and how it had changed the way he used his remaining senses.

Finding out about him has been an odd task. I can speak a sort of fluent pidgin Spanish, which means I can talk to people at length if they are patient with me, but even with the help of a big dictionary I can only struggle through a few pages of written Spanish, and so for the most part I have had to depend on what has been published in English or in French. But whenever I lost courage I would remind myself that even someone much more qualified than me could only try to piece together the narrative of Goyas life from the fragments of information that have survived him. The inventory from the sale of a house might prove when a particular painting was done; a drawing of a naked woman might suggest a love affair; a passing comment in a letter might indicate a political opinion. Or not. Goya leaves everyone free to make their own interpretation of the kind of person he was; what he believed in or did not believe in; who he loved and did not love; and whether he was tormented by savage nightmares that brought him close to madness or was simply a witness to a time in history when nightmares of one sort or another were being enacted on the streets and in the open countryside every day of the week.

In order to try to see what Goya saw, I have visited the places he knew well: the village of his childhood, the farmhouse where he stayed with the Duchess of Alba, the cities of Zaragoza, Madrid, Cadiz and, finally, Bordeaux. In my minds eye I can now look across the landscapes that he once travelled through, I can walk the same streets, I can gaze out of the window of the house in which he was born and the house in which he died. Maybe that is another way of meeting a man who is dead.

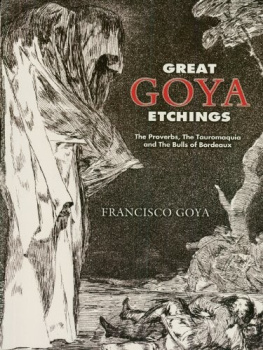

In the telling of this story I have concentrated on what happened to Goya after the illness which made his world turn silent and forced him to depend upon his eyes for everything. Instead of illustrations of his drawings or paintings I have included some photographs of his etching plates. I wanted to use them because here you can see what he saw while he was working; you can see the huge energy of the man as he scratched and scraped and burnt the images he was creating on the surface of the metal.