Francisco de Goyaand the Art of Critique

Francisco de Goyaand the Art of Critique

Anthony J. Cascardi

ZONE BOOKS NEW YORK

2022

2022 Anthony J. Cascardi

ZONE BOOKS

633 Vanderbilt Street

Brooklyn, NY 11218

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except for that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the Publisher.

Distributed by Princeton University Press,

Princeton, New Jersey, and Woodstock, United Kingdom

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cascardi, Anthony J., 1953 author.

Title: Francisco de Goya : art of critique / Anthony J. Cascardi.

Description: New York : Zone Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: The subject of this book is the relationship between the enormous, extraordinary, and sometimes baffling body of Goyas work, and the interconnected issues of modernity, in art, the Enlightenment, and the project of critiqueProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021048502 (print) | LCCN 2021048503 (ebook) | ISBN 9781942130697 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781942130703 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Goya, Francisco, 1746-1828Aesthetics.

Classification: LCC N7113.G68 C27 2022 (print) | LCC N7113.G68 (ebook) | DDC 759.6dc23/eng/20211231

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021048502

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021048503

Version 1.0

For Jennifer, and the joys of critique

Contents

Introduction

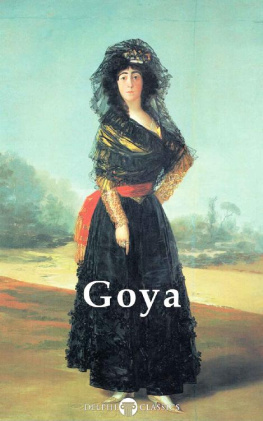

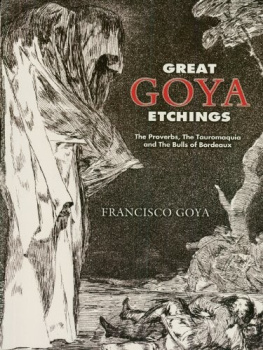

My subject in this book is the relationship between the enormous, extraordinary, and sometimes baffling body of Francisco de Goyas work and the interconnected issues of modernity, Enlightenment, and critique. This is admittedly a very large topic, but my hope in considering it is that it might help shed some light both on some of the difficulties that Goyas work presents and on the paradoxes of Spanish modernity while establishing that Goya was dedicated throughout his career to the making of art in the service of critique. As for the apparent inconsistencies within Goyas work and its relationship to Enlightened modernity, consider, for example, the fact that Los desastres de la guerra (Disasters of War) seem to presage the truth-telling function of modern photojournalism, while Spain is often cast as retrograde and reactionary when it comes to a model of modernity that hinges on Enlightenment values. Goyas so-called Black Paintings are often thought to represent fearless journeys into regions of the psyche that were charted only much later, by figures such as Ludwig Kirchner and Edvard Munch. The influence of the Black Paintings on the history of modern art is a subject often commented upon by art historians. And yet Goyas portraits of aristocrats are elegantly sedate and mostly conformist, while his colorful and light-filled tapestry cartoons seem to portray the leisure activities of a society too happy to be troubled by even the most disturbing domestic and international events.

I take exception to the standard view that relies predominantly on Goyas darkest images to establish his relevance for modernity, and I suggest instead that his work invites us to consider the critical role of art with respect to the modern social and historical worlds, worlds of which it is nonetheless a part. For one thing, the standard views are not altogether coherent, either about Goya or about modernity in art more generally: with respect to Goya, they locate the truth function of art sometimes in a figural literalism (for example, of the Disasters of War) and sometimes in fantastical realism (for example, of the Black Paintings), and then with respect to modern art more generally, they simply flatten the curve of these contradictions by telling a story of the eclipse of figuration by abstraction. Yet these very contradictions are among some of the difficulties that the corpus of Goyas work seems to embrace, rather than resolve. They hardly do justice to Goyas oeuvre as a whole, where the inconsistencies are manifest. Indeed, we do well to reckon with the gulf that seems to divide the Disasters of War and the Black Paintings, on the one hand, from Goyas scenes of bourgeois life or from the well-mannered portraits of aristocrats, military men, and intellectuals, on the other. What I want to suggest here is that these apparent contradictions themselves offer us the gateway into a vision of the critical function of art within the framework of a modernity that many tend to associate with the dominant Enlightenment values of Germany, England, and France. Call it a vision of aesthetics as critique, one that both identifies itself with and distances itself from what we regard all too broadly and uniformly as the Enlightenment.

What is critique? To the work of criticism, critique adds a self-conscious dimension that incorporates reflection on history, on tradition, on the underlying accepted categories and conditions of knowledge and belief, as well as on the medium through which these are represented. The chapters that follow are meant to illuminate Goyas adherence to this projecta project carried out, perhaps needless to say, within the nondiscursive field of visual art. This affords an alternative to the standard readings of Goyas work, many of which acknowledge the explicit social criticism evident in certain parts of it (for example, the Caprichos), but that have little to say about those parts of his work that are not explicitly engaged in the work of social criticism. Indeed, the field of social relations is but one of many with which Goyas project of critique is engaged. In order to convey the diversity of those engagements and to capture Goyas relentless pursuit of the project of critique, the chapters that follow focus on a number of the different fields with which Goyas work is critically engaged: religion and its antitheses (in secularism, on the one hand, and superstition, on the other); society (taking into account the valuation of happiness as associated with the nascent bourgeoisie, as well as the self-deception that social relations can enable); the individual (taking into account the role of portraiture as the form of art in which the dignity of the subject was made canonical, beginning in the Renaissance); history (including the representation of large-scale forces, such as revolution); and the psyche (interpreting questions of desire in the Black Paintings and the depictions of violence and the drive toward death in the bullfight images).

Much of this involves an account of Goyas critical relationship to conventions that had become well established in the visual arts for rendering a truthful likeness of the world. I argue that Goya came relatively early in his career to reflect on the means by which any view of the world, including any view of art as creating a faithful image of the world, is constructed and sustainedinvented, rather than naturaland invented in ways that are often concealed by the very conventions that enable it. That recognition, I argue in , was underpinned by a process of secularization that was nonetheless incomplete. It was a process that enabled the creation of images of the world by the use of rational visual perspectives as a means of organizing space (the convention known as artificial perspective), but it did not root out all the possible irrational causes of fear, anxiety, and violence that continued to haunt the world. It was also, as Goya makes plain, a wholly artificial process with no inherent claims to truth, albeit one that was made to appear as if it were wholly natural.