DISASTER DRAWN

VISUAL WITNESS, COMICS, AND DOCUMENTARY FORM

HILLARY L. CHUTE

THE BELKNAP PRESS of HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts | London, England

2016

Copyright 2016 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Jacket art: Srebrenica, July 1995; from Joe Sacco, Safe Area Gorade; used by permission of Joe Sacco.

Jacket design: Jill Breitbarth

978-0-674-50451-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

978-0-674-49566-1 (EPUB)

978-0-674-49565-4 (MOBI)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Chute, Hillary L.

Disaster drawn : visual witness, comics, and documentary form / Hillary L. Chute.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Comic books, strips, etc.History and criticism. 2. Nonfiction comicsHistory and criticism. 3. Graphic novelsHistory and criticism. 4. Psychic trauma in literature. 5. Storytelling in literature. 6. Narration (Rhetoric) I. Title.

PN6714.C487 2016

741.5'9dc23 2015017876

For my parents, Richard and Patricia Chute, the two people I respect and admire most

And for Shahab Ahmed

CONTENTS

A NOTE ON THE FIGURES

All images presented here as figures appear at or close to their actual size. I have not enlarged any images, although some by necessity (double spread pages, for example) appear smaller than they do in print.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyrighted images. I would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Form is the record of a war.

NORMAN MAILER, CANNIBALS AND CHRISTIANS, 1966

My interest in comics as nonfiction as a form of documentary, as a form of witnessingbegan with realizing how comics as a medium places pressure on classifiability and provokes questions about the boundaries of received categories of narrative. In 1991, cartoonist Art Spiegelmans Maus anyway. Comics narrative, howeverwhich calls overt attention to the crafting of histories and historiographiessuggests that accuracy is not the opposite of creative invention.

Why, after the rise and reign of photography, do people yet understand pen and paper to be among the best instruments of witness? There are many examples of the visual-verbal form of comics, drawn by hand, operating as basic grammar, by aggregating and accumulating frames of information.

Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form explores how the form of comics endeavors to express historyparticularly war-generated histories that one might characterize as traumatic. For that reason, it is centrally about the relationship of form and ethics. How do the now-numerous powerful works about world-historical conflict in comics form operate? To what end, aesthetically and politically, do they visualize testimony? How do they engage spectacle, memory, and lived livesas well as extinguished lives? While the works I discuss here are each rooted in a different way in traumatic history, they all propose the value of inventive textual practice to be able to express trauma ethically. (By textual practice, I refer to the space of the comics page in its entiretythat is, to work in both words and images.)

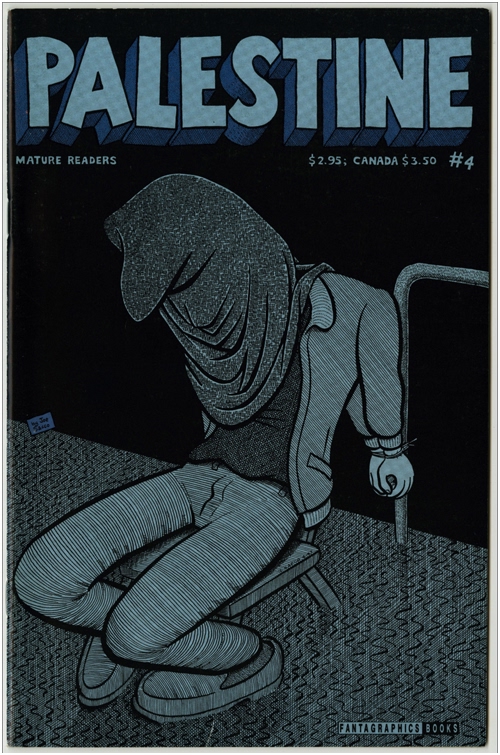

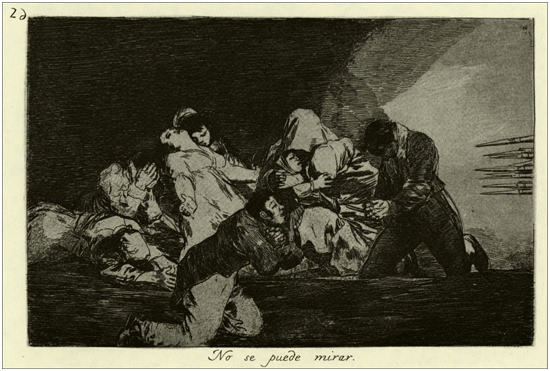

Figure I.1 Joe Sacco, cover to Palestine comic book #4, 1993. Palestine was a series before it was collected as a single book volume in 2001. (Used by permission of Joe Sacco.)

I have written on comicss visual form as an ethical and troubling visual aesthetics, or poetics, in Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. That book takes up the question of ethics in relation to notions they are genealogical narratives of family history, or by the weight of history on family structures.

Two features of the medium particularly motivate my interest in how comics expresses history. First, comics is a drawn form; drawing accounts for what it looks like, and also for the sensual practice it embeds and makes visible, which I treat here as relevant to the forms aesthetics and ethics.

In asking why there are so many difficult and even extreme

Disaster Drawn analyzes the substance and emergence of contemporary comics; it connects this work to practices of witnessing spanning centuries. In placing earlier documentary traditions in conversation with those of modern comics, I focus on contemporary

This book makes two historical arguments, claiming that the forceful emergence of nonfiction comics in its contemporary specificity is based on a response to the shattering global conflict of World War IIand also that we need to see this work as adding to a long and in the United States, when the form established the conventions recognized widely today.

Second, I investigate the social and psychic pressures that impelled the forms reemergence after World War II, and the formal innovation across national boundariesalong with the global routes of circulationthat comics took and created.

Finally, in

The past centurys debates about documentary have been almost wholly about theorizing the filmic and the televisualor the photographic. (One recent exception is Lisa Gitelmans Paper Knowledge, about how genres of the document such as the photocopy and the PDF become epistemic objects.) In Disaster Drawn, I work against this idea, as do Latour and others, by exploring comicss documentary properties and aspirations.

War Comics

Disaster Drawn is the first book to present a substantial historical, formal, and theoretical context for contemporary practices of war had produced a new visual idiom.

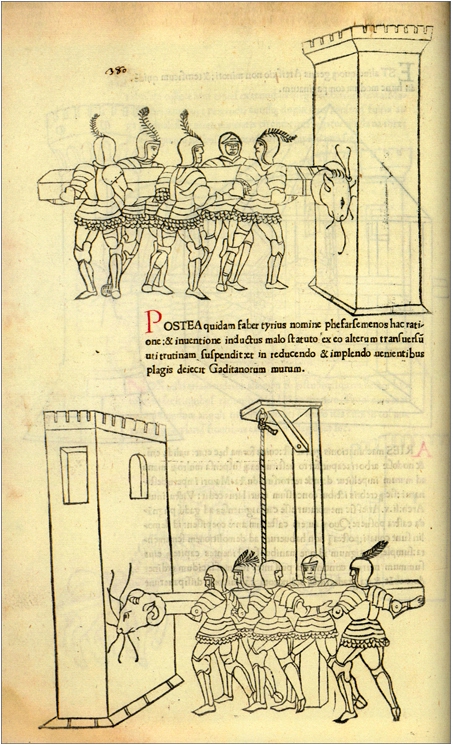

As the movement of its chapters makes clear, this book traces a history that understands contemporary comics as part of a long trajectory of works inspired by witnessing war and disasterworks that in turn created new idioms and practices of expression. It considers visual-verbal forms of witnessing war going back to the influential French printmaker).

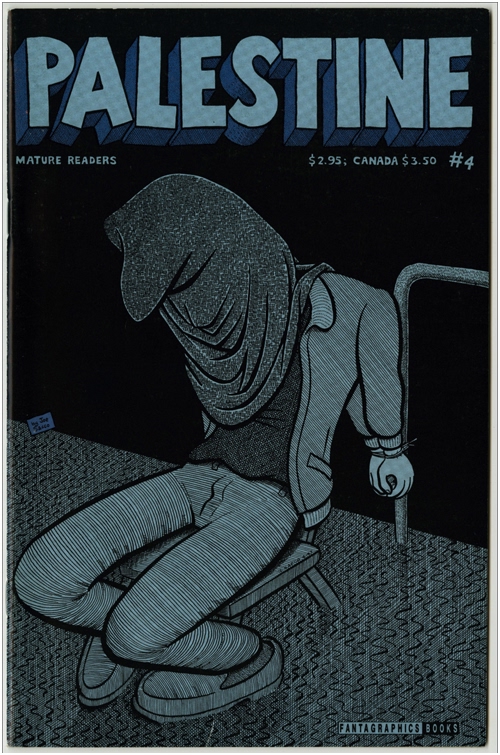

Figure I.2 Robertus Valturius, from De Re Militari, 1472.

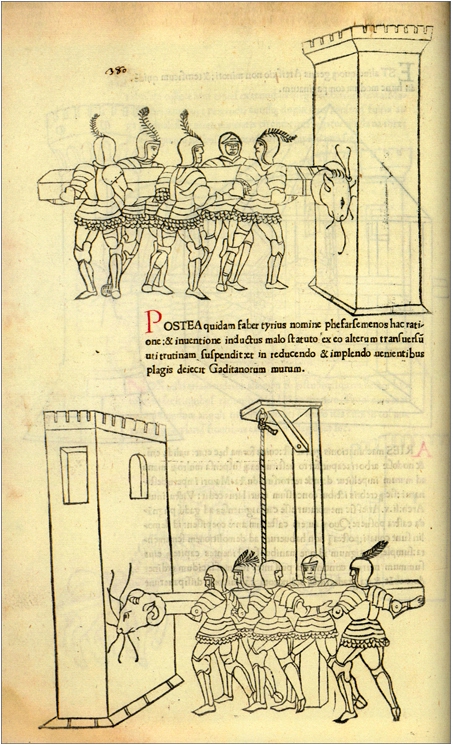

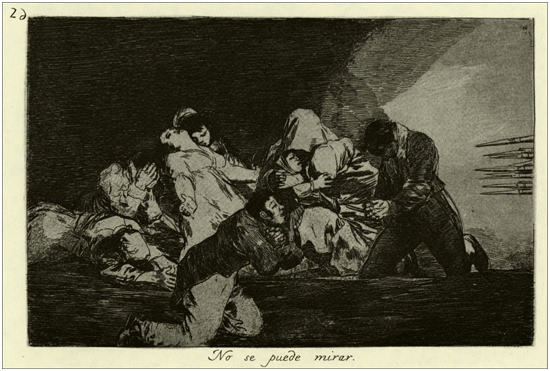

Figure I.3 Francisco Goya, One cannot look at this, plate 26, The Disasters of War, 1810s, published 1863. (Image courtesy of Dover Publications.)

A new category of artist-reporter essentially developed in relation to war, in particular the Crimean War (18531856). This was despite the fact that war photography, such as that of Roger Fenton, considered one of the first war photographers, Hearst sought to claim new, largely immigrant readers. What is widely recognized as the first American comics work, Richard Felton Outcaults The Yellow Kid (or Hogans Alley), appeared in 1895 in the New York World; Hearst soon stole the cartoonist away from Pulitzer, giving rise to the term yellow journalism.

This is a period in which the appearance of comics in newspapers, taking on a range). At every corner of its history, comics, or its antecedents, takes shape in conversation with war.

During World War II, fictional comics in the form of comic books, a format that began in 1929 as bound, floppy commercial inserts, were at an all-time high, selling at one point 15 million copies a week. It is worth noting that plenty of fictional comics arose explicitly in the context of the war;).

Next page