Hiroshima

ASIAN VOICES

A Subseries of Asia/Pacific/Perspectives

Series Editor: Mark Selden

Tales of Tibet: Sky Burials, Prayer Wheels, and Wind Horses

edited and translated by Herbert Batt, foreword by Tsering Shakya

Tiananmen Moon: Inside the Chinese Student Uprising of 1989

by Philip J Cunningham

Peasants, Rebels, Women, and Outcastes: The Underside of Modern Japan

by Mikiso Hane

Comfort Woman: A Filipinas Story of Prostitution and Slavery under the Japanese Military

by Maria Rosa Henson, introduction by Yuki Tanaka

Japans Past, Japans Future: One Historians Odyssey

by Ienaga Sabur o , translated and introduced by Richard H. Minear

Im Married to Your Company! Everyday Voices of Japanese Women

by Masako Itoh, edited by Nobuko Adachi and James Stanlaw

Queer Japan from the Pacific War to the Internet Age

by Mark McLelland

Behind the Silence: Chinese Voices on Abortion

by Nie Jing-Bao

Rowing the Eternal Sea: The Life of a Minamata Fisherman

by Oiwa Keibo, narrated by Ogata Masato, translated by Karen Colligan-Taylor

The Scars of War: Tokyo during World War II, Writings of Takeyama Michio

edited and translated by Richard H. Minear

Growing Up Untouchable in India: A Dalit Autobiography

by Vasant Moon, translated by Gail Omvedt, introduction by Eleanor Zelliot

Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japans Cold War

by Tessa Morris-Suzuki

Hiroshima: The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen

by Nakazawa Keiji, edited and translated by Richard H. Minear

China Ink: The Changing Face of Chinese Journalism

by Judy Polumbaum

Sweet and Sour: Life-Worlds of Taipei Women Entrepreneurs

by Scott Simon

Dear General MacArthur: Letters from the Japanese during the American Occupation

by Sodei Rinjir o , edited by John Junkerman, translated by Shizue Matsuda, foreword by John W. Dower

Unbroken Spirits: Nineteen Years in South Koreas Gulag

by Suh Sung, translated by Jean Inglis, foreword by James Palais

No Time for Dreams: Living in Burma under Military Rule

by Carolyn Wakeman and San San Tin

A Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sisters

by Sasha Su-Ling Welland

Dancing in Shadows: Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge, and the United Nations in Cambodia

by Benny Widyono

Voices Carry: Behind Bars and Backstage during Chinas Revolution and Reform

by Ying Ruocheng and Claire Conceison

For more books in this series, go to www.rowman.com/series

Hiroshima

The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen

Nakazawa Keiji

Edited and Translated by

Richard H. Minear

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2010 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nakazawa, Keiji.

[Hadashi no Gen jiden. English]

Hiroshima : the autobiography of Barefoot Gen / Nakazawa Keiji ; edited and translated by Richard H. Minear.

p. cm. (Asian voices)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-0747-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-0749-3 (electronic)

1. Nakazawa, Keiji. 2. CartoonistsJapanBiography. 3. Comic books, strips, etc.JapanHistory. 4. Nakazawa, Keiji. Hadashi no Gen. 5. Nakazawa, KeijiChildhood and youth. 6. Nakazawa, KeijiFamily. 7. Atomic bomb victimsJapanHiroshima-shiBiography. 8. Hiroshima-shi (Japan)HistoryBombardment, 1945Personal narratives. 9. Hiroshima-shi (Japan)Biography. 10. JapanBiography. I. Minear, Richard H. II. Title.

NC1709.N26A2 2010

741.5'952dc22

[B]

2010020806

` The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Editors Introduction

Richard H. Minear

Many in the English-speaking world need no introduction to Barefoot Gen . They have read the manga, available in ten volumes in fine translation, or they have seen the animated movie, available on YouTube and elsewhere. Barefoot Gen is already international. It started in Japan, as a manga serial, in 1973. Then a relatively unknown manga artist, Nakazawa Keiji completed the serial in 1985. By then it had grown into a ten-volume book. Barefoot Gen s Japanese readers number in the many tens of millions. And there have been film versions: a three-part live-action film (19761980), a two-part anime (1983 and 1986), and a two-day television drama (2007). There is a book of readers responses, Letters to Barefoot Gen . On GoogleJapan, Hadashi no Gen returns more than two million hits.

What has its impact been outside of Japan? In the late 1970s there was a first, partial English translation of the manga. It has now appeared in a second, complete translation (Last Gasp, 20042009). Volume I has an introduction by Art Spiegelman, creator of Maus . Spiegelman begins: Gen haunts me. The first time I read it was in the late 1970s, shortly after Id begun working on Maus .... Gen effectively bears witness to one of the central horrors of our time. Give yourself over to... this extraordinary book. R. Crumb has called the series Some of the best comics ever done. Wikipedia has articles on Barefoot Gen and Keiji Nakazawa and on the films, the anime, and the television drama. On YouTube, the anime sequence of the dropping of the bombin Englishhas racked up more than one hundred thousand views, and the rest of the anime is also available. There are translations into Dutch, Esperanto, German, Finnish, French, and Norwegian, with others in the works.

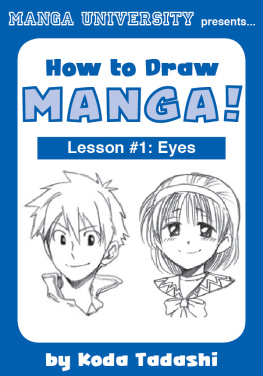

The Autobiography of Barefoot Gen may well come as a surprise to those in the English-language world who dont read manga or watch anime. I hope it will lead them to seek out both versions. Even those who already know Barefoot Gen may wish to relive that story in a different genre. After all, manga has its conventions, and they differ from the conventions of prose autobiography. In his introduction to the ten-volume English translation of the manga, Spiegelman mentions the overt symbolism as seen in the relentlessly appearing sun, the casual violence as seen in Gens fathers treatment of his children, and the cloyingly cute depictions. Under the latter category Spiegelman discusses the Disney-like oversized Caucasian eyes and generally neotenic faces. Neotenic? Websters Encyclopedic Dictionary (1989) defines neoteny as the retention of larval characters beyond the normal period; the occurrence of adult characteristics in larvae. Spiegelman has the latter definition in mind: consider our cover and its faces of Gen, age six, and Tomoko, a few months old.

Apart from the illustrations he drew specifically for the autobiography, those conventions do not apply to Nakazawas autobiography. Beyond the conventions Spiegelman mentions, I would comment that even though he writes of the extreme hunger that most Japanese experienced in 1945, he depicts all of his characters as remarkably well-fed. Such is also the case with the almost Rubenesque figures in the Hiroshima screens of Iri and Toshi Maruki. Nakazawa had no formal training in art, but perhaps conventions of the art world trumped memory.