Table 1. Forms of interventions and their status

Preface

On 29 August 2012, a day after Tom Hollands debatable documentary Islam: The Untold Story (based on his book In the Shadow of the Sword) was broadcast on Britains Channel 4, journalist-writer Ed West published a blog post in the Telegraph titled Can Islam Ever Accept Higher Criticism? West (2012) summarized the aim of the atmospheric and intelligent documentary as an examination of the early history of the religion [Islam]... to explain what evidence we have for the traditional history, as viewed by the faithful. Quoting from Holland, West concluded that this evidence is almost non-existent. In the rest of his post, West gave one piece of evidence after another to endorse Hollands documentary. To mobilize credibility for the film, West clarified that Holland was not anti-Islam. Toward the end of his post, West referred to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, a well-known scholar of Islam at George Washington University who appears in the documentary, as follows: He feels culturally under attack from Western-dominated criticism. West concluded with patronizing advice: If the Islamic world is to go forward... it needs to face these uncomfortable questions and embrace the pain of doubt.

West aimed to show that Islam knows no critique and is unlikely to embrace critique in the future, as the title of his post made amply clear. For West, even a professor like Nasr is threatened by Western-dominated criticism. That Muslims have been and are critics was well beyond Wests ken. Importantly, in posing the question, Can Islam Ever Accept Higher Criticism? it never occurred to West that his own commentary on Holland in the Telegraph was far from critical.

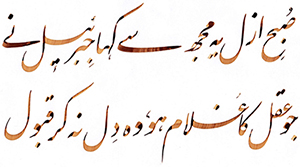

In contrast to the conventional wisdom on Islam exemplified by Wests blog post in the Telegraphand shared widely by most academics, nonacademic intellectuals, and the general publicReligion as Critique: Islamic Critical Thinking from Mecca to the Marketplace demonstrates multifaceted thriving traditions of critique in Islam, laying bare the principles, premises, modes, and forms of critique at work. It discusses believers in Islam as dynamic agents, not mere objects, of critique, for which the standard word in Urdu is tanqd or naqd. Based on ethnographic fieldwork in India, it foregrounds critique and tradition as subjects of anthropological inquiry in their own right. Since tradition is reducible neither to nationalized territory nor to its official temporality, the book travels across both. Departing from standard Enlightenment understandings, according to which religions, especially non-Protestant ones, could only be objects of critique, this book in your hands or on your screen theorizes religion as an important agent of critique, viewing Moses, the Buddha, Christ, Muhammad, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Abul Ala Maududi, and many others as critics par excellence. In the course of this inquiry, Religion as Critique offers a different genealogy of critique in Urdu/Islam, transcending as it does ancient Greece and its assumed inheritor, the modern West, as the customary prime loci of critique. Using an anthropology of philosophy approach, it interprets the Wests Enlightenment as a sign of its ethnic identity, thereby calling its universalism into question. Engaging with literature on the anthropology of the Enlightenment, it brings the Western Enlightenment tradition of critique into conversation with Islamic tradition to analyze differences as well as similarities between the two. Beyond perfunctory apologia such as, Muslims also have a notion of critique like the West has, it argues for the specificity of Islam and the need for a genuinely democratic dialogue with different traditions. As it examines the contours and parameters of critique, using sources in English, Hindi, Farsi, and Urdu, it expands the scope of critique, hitherto confined to canonical texts and extraordinary individuals, like salaried philosophers, academics, critics, and intellectuals, to the everyday life intertwined with death of ordinary actors such as street vendor, beggars, and illiterate peasants. In short, Religion as Critique brings critique to the academic stage as an ordinary social-cultural practice with an extraordinary salience. Rather than present critique as an isolated, merely mental exercise, the book aspires to lay bare the very life critique belongs to and seeks to enunciate. Thinking past the available descriptions of critique as unmasking, disclosing, debunking, and deconstructing (Fabian 1991), it argues that critique is simultaneously a work of assemblage and disassemblage, with signposts to a world to come. By its very nature, it is neither neutral nor objective in the sense that these twin words are usually understood or used to claim impartiality, even detachment. In many ways, critique indeed presupposes some degrees of attachment as well as detachment.