Acknowledgments

The finished book, complete with hard binding and glossy cover, has a way of concealing how arduous and at times tenuous the long enterprise has been. I want to acknowledge all those who have fueled my fire and guided my journey as well those who have offered the warmth of their help, support, and companionship along the way.

My gratitude goes first to Christopher Hill whose courses on history and literature expanded my literary and political imagination, introducing a historical consciousness and an ethical imperative to my literary readings. This book was inspired by his many teachings and would not have been possible without his genial guidance and sage counsel. I also owe more than I know to John Treat who taught me that scholarship is not just an intellectual enterprise but a self-search. He helped me learn to trust myself, have faith in my own instincts, and to have the courage to take big swings. In Japan, Toeda Hirokazu was unbelievably generous and unceasingly gracious with his time, his mentorship, and his friendship. I am eternally grateful.

I have been extremely fortunate to receive institutional support for my studies. The dissertation research from which this book emerged was conducted with grants from the Japan Foundation and the Yale University Council on East Asian Studies, and the final manuscript was completed while on a sabbatical leave supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Social Science Research Council, and Macalester College. The final phase of publication was aided by a Wallace Grant from Macalester College. I owe a great debt of gratitude to Waseda University for hosting many years of my research and in particular to the Waseda Central Library. Their archive of periodicals laid out in open stacks was my scholarly sandbox for several years and the kindness of their dedicated librarians were for countless months a daily encouragement.

Several people had a direct impact on this book. Seiji Lippit and William Gardner were there at the ground floor and their early guidance helped me chart my course and set sail. Their monographs on Japanese modernism paved the way for me to say everything I have said on the subject. Pericles Lewis believed in my work and gave me the confidence to take on such a big topic. Edward Kamens invited me into the field itself and gave me my foundation in Japanese literary analysis. I would like to thank Mai Shaikhanuar-Cota and Alexis Siemon, my editors at Cornell University Press, for their care and commitment to this manuscript, and Ross Yelsey, formerly at the Columbia University Weatherhead East Asia Institute, for recognizing the book and helping it take its first steps into the world of publication. I would also like to thank Paul Anderer for believing in my work and helping me get the publication process started. For their invaluable feedback on different sections of the book, I would like to thank Reiko Abe Auestad, David Blainey, Jim Dorsey, Aaron Gerow, Rivi Handler-Spitz, Reto Hofmann, Inoue Ken, Kate Nakai, Haruko Nakamura, Chelsea Scheider, Angela Yiu, and the anonymous readers for WEAI and CUP.

For their conversation and invaluable friendship during these years, I would like to particularly thank, Will Bridges, John Graves, Kendall Heitzman, Shuntar Kishikawa, Christine Marran, Mariko Nait, Yasufumi Nakamori, Patrick Noonan, Marcos Ortega, Parker Smathers, Luciana Sanga, Brian Steininger, Ellen Tilton, Daniel Williams, Naoki Yamamoto, Shichir Yamashita, and the members of La Fondation. And for their essential encouragement and mentorship, or for simply providing a warm family table, I would like to thank, Barbara Bassous, Ernie Bassous, Steve Focios, Satoshi Hamaya, Rashed Judeh, Mutsuko McIlroy, Robert McIlroy, Masato Ogura, John Reinartz, Satoko Suzuki, and Michiko Yoshida. Finally, I want thank my parents, my sisters, Sono and Kano, and Ella for her love and her marvelous meals.

This book is very much about the vital importance of literary art. For feeding this faith in me I would like to thank James Shea, Tracy Dahlby, Ai Kud, and Marie Focios.

I dedicate this book to my father, who taught me how to think and introduced me to the world.

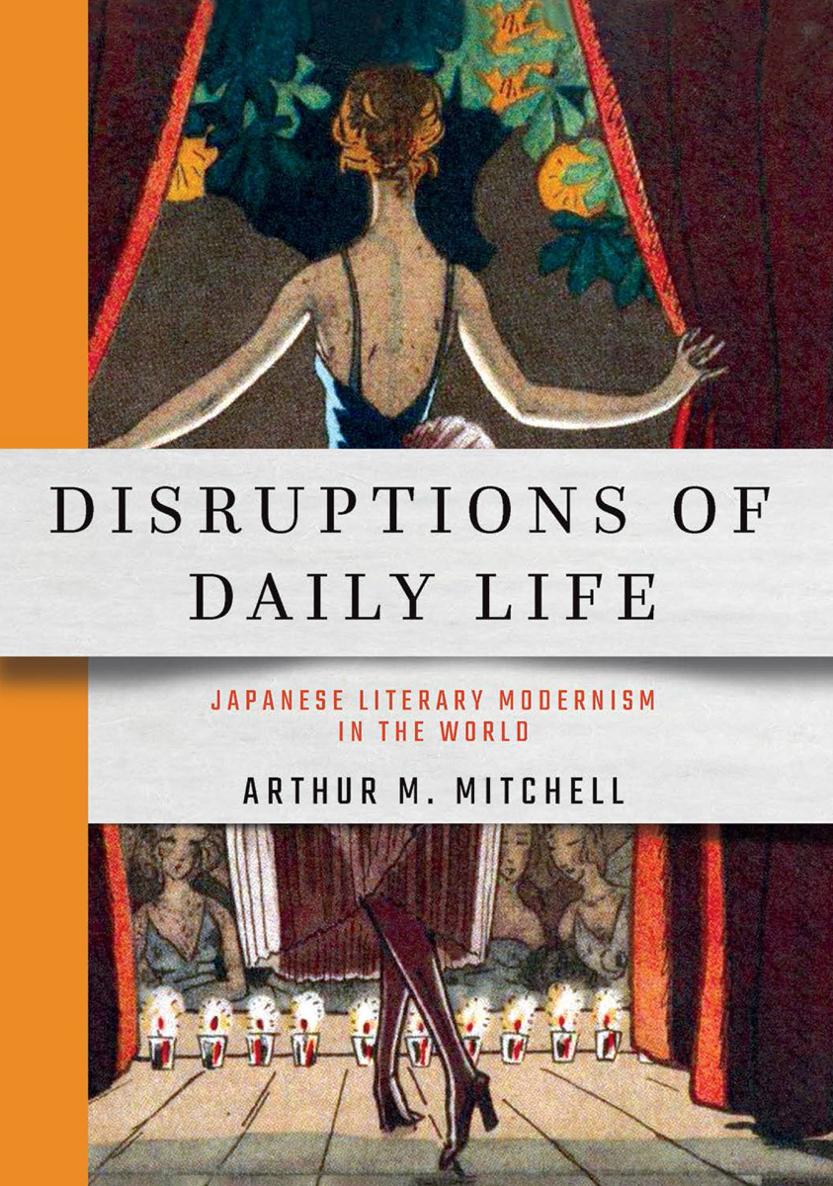

Introduction

SHATTERING THE STATUS QUO: READING MODERNISM IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY

Disruptions of Daily Life explores the ability of formalist literary narratives to interrupt the sense of dailiness that we all inhabit. It traces and clarifies how certain types of narrative fiction can make us aware of the discursive structures that undergird the imaginative relationship we have to our social world, thereby displacing the hold these structures have on our lived realities. By confirming and elaborating how this function operated historically, as it worked for contemporary Japanese readers in the 1920s, I want to suggest that such works continue to serve this function for us in the present day. Focusing on a handful of textssome major, some not yet widely known, some recognized as modernist literature and some not yetby Tanizaki Junichir, Yokomitsu Riichi, Kawabata Yasunari, and Hirabayashi Taiko, I show how the potency of their formalist disruptions had everything to do with their deep interconnections with the social discourses operative within the media of that decade. Contrary to prevalent conceptions of high modernism as art-objects sequestered from the utilitarian language of capitalist society, modernist literature was highly enmeshed in the language of the mass print media, one of the major sources of social ideology since the beginning of the twentieth century. Indeed, it was through this nexus that modernist formalism attained its subversive edge.

This book arose from an inkling that the real-world significance of modernist literature was getting lost in the scholarly gap that emerged between textual hermeneutic approaches that focused purely on the craft of the material text and cultural studies approaches that focused exclusively on the historical and cultural circumstances of its production. The effectiveness of modernist fiction was rooted in the intersection between the two, in the representational distortions of historical culture. Readers can expect on the one hand close textual analyses of the works being treated here. But these close readings are performed in the context of a detailed and concrete history of social thought in 1920s Japan. In my approach to modernist fiction, the two vectors of textual analysis and historical study are not just contiguous but intimately interrelated. I read works deeply and formally for the ingenuity of their design and textual play while, at the same time, I locate the linguistic source of these representational strategies empirically within the print media of that time. As a result, the language of literature is understood not as purely linguistic signs, but simultaneously as linguistic signs embedded in and operative within late-Taish and early-Shwa society. The myriad social nuances and connotations of that language were, I argue, indeed the ultimate targets of modernisms disruptive strategies. Though it has been well established that works of modernist literature are characterized by a reflexive awareness of the signifying operations of linguistic conventions, I show here how that reflexivity in fact applied to the language that circulated throughout the social institutions of modern Japanese society.