CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY

A series edited by Philip V. Bohlman, Ronald Radano, and Timothy Rommen

Editorial Board

Margaret J. Kartomi

Bruno Nettl

Anthony Seeger

Kay Kaufman Shelemay

Martin H. Stokes

Bonnie C. Wade

COMPOSING JAPANESE MUSICAL MODERNITY

BONNIE C. WADE

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

BONNIE C. WADE is professor of music at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of many books, including Imaging Sound: An Ethnomusicological Study of Music, Art, and Culture in Mughal India, also published by the University of Chicago Press, and, most recently, Music in Japan: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2014 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2014.

Printed in the United States of America

23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-08521-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-08535-7 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-08549-4 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226085494.001.0001 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wade, Bonnie C., author.

Composing Japanese musical modernity / Bonnie C. Wade.

pages cm (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-08521-0 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-08535-7 (paperback : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-08549-4 (e-book)

1. ComposersJapan. 2. MusicJapanWestern influences. 3. MusicJapan20th centuryHistory and criticism. I. Title. II. Series: Chicago studies in ethnomusicology.

ML340.5.W33 2014

780.952dc23

2013014448

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My first acknowledgment goes to the many individuals in Japan who welcomed me graciouslycomposers, composer-performers, performers, and the heads of agencies and companies as well as their numerous staff members. They are simply too many to list here. The consistent rapidity of the responses that came to telephone calls, faxes, and letters and the amount of time that individuals were willing to spend with me while I was in Japan for field research was amazing, and I am enormously grateful. The assistance of the staff at the International House of Japan in Roppongi, where I make my home in Tokyo, needs special mention; the number of faxes they sent and received for me every time I was there made them seem rather like part of the project, and they welcomed my visitors cordially.

I wish to acknowledge with affection and gratitude the support of a few people in Japan. The Nakajima family, whom I have known since 1964, is always welcoming and supportive, as is the koto artist Keiko Nosaka, who established a number of important connections for me and in whose home there were always gatherings during my annual sojourns. The musicologist Tokiko Inoue was willing to speak with me about historical European music in Japan, and Fukiko Shinohara responded each time I need translation assistance either for a meeting or at International House, where we worked for hours together with recordings of conversations.

Kimiko Shimbo, whom I met on my first ethnographic foray in 1999 because she was included as a woman composer in the Whos Who (see the Japanese life, by giving me invitations to concerts, by taking me along to private receptions after events, by meeting with me to clarify something or explain the significance of thingsfar exceeded the part of her job description that required her to foster international relations for Japanese composers; I will forever be grateful for her guidance and assistance.

Going to Japan for research is expensive. In this regard (and others), I am blessed to be a professor at the University of California, which afforded me the luxury of multiple sources of fundingspecifically the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Chair in Interdisciplinary Studies of the College of Letters and Science at Berkeley; and support from the Center for Japanese Studies for my graduate student research assistantsMari Abe, and Muyang Chen, Miki Kaneda, Alexandre Youngki Kwon, Sangbec Lee, and Adam Stecklerwho helped me mine the considerable resources of the East Asia Library, do translations, and check translations, for example. I wish to thank the staff in the Department of Music, at the Center for Japanese Studies, and at the Institute for East Asian Studies, who guided me through the procedures the university requires for using such funds.

Among my colleagues at Berkeley, I want to thank the historian of modern Japan Andrew Barshay for reading pertinent parts of the draft. The readers of the manuscript for the University of Chicago Press were helpful, as was the editorial associate Russell Damian in the production process. For our conversations during the writing process and her early readings, I give hearty thanks to the editor Elizabeth Branch Dyson. The comments and endorsement of Ronald Radano on behalf of the Chicago Series in Ethnomusicology were greatly appreciated.

Finally, for her patience, encouragement, and lots of help along the way, I especially thank Ann Pescatello.

Bonnie C. Wade

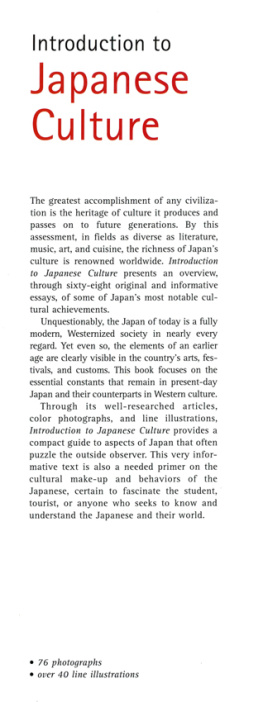

Japanese children sing God Save the King in honor of the visit of the Prince of Wales on January 1, 1921. (Bain News Service)

INTRODUCTION

This is a book about composers in Japan, by which I mean musicians who, at least part of the time, create new music. They are professional and amateur, female and male, academic and freelance, innovative and conservative, well-known and ignored, and they work from a base in either European or traditional music. Such a persona as a composer has not always existed in Japanese culture; creators of new music have been of two kindsperformer-composers and composers. Who the creator of new music is changed during Japans process of absorbing and normalizing in Japanese culture music from Europe and Americaa process that took about fifty years past an initial governmental decision to do so in 1872.

Composers in premodern Japanese society were professional performers of one musical repertoire or another who also created new musicthat is, they were performer-composers. In the immediate premodern period of Japanese history (the Tokugawa shogunate, 16001868), those musicians functioned relationally, in the context of some particular social group such as courtiers, samurai elites, urban populations of merchants and workers, and religious sects. Accordingly, the works they created fit into some particular repertoire such as music for the court, music for private entertainment, music for the popular theater, and music for Zen meditation. While amateur individuals such as wealthy (but low-status) merchants might study an instrument or vocal genre that fit into one of those realms to which they did not belong socially, the right to transmit musical knowledge was limited to professionals, with some spheres of music organized into guilds chartered by the government. While some degree of innovation could and did occur within or across musical spheres, until the nineteenth century new music created by performer-composers wandered only so far stylistically from existing music. One might say that new compositions were musically as well as socially relational.

The persona of the performer-composer still exists in modern Japan. I use the term herein to indicate an individual whose musical creativity is informed first and foremost by their competence and situatedness as a performer. Most of them discussed here are based in some sphere of traditional musicplayers of the

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).