Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2012 by Julia Kennedy Cochran and Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

DESIGNER: Michelle A. Neustrom

TYPEFACE: Chaparral Pro

PRINTER: McNaughton & Gunn, Inc.

BINDER: Acme Bookbinding

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

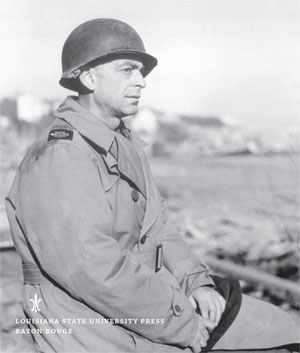

Kennedy, Ed, 19051963.

Ed Kennedys war : V-E Day, censorship, and the Associated Press / Ed Kennedy ; edited, with a prologue and epilogue, by Julia Kennedy Cochran ; with an introduction by Tom Curley and John Maxwell Hamilton.

p. cm. (From our own correspondent)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8071-4525-8 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-4526-5 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-4527-2 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8071-4528-9 (mobi) 1. Kennedy, Ed, 19051963. 2. World War, 19391945Press coverage. 3. World War, 19391945Censorship. 4. World War, 19391945Personal narratives, American. 5. V-E Day, 1945. 6. Government and the pressUnited StatesHistory20th century. 7. War correspondentsUnited StatesBiography. 8. Associated PressBiography. 9. Associated PressHistory20th century. I. Cochran, Julia Kennedy, 1947II. Title.

D799.U6K46 2012

070.4'4994053092dc23

2011043189

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Introduction

TOM CURLEY AND JOHN MAXWELL HAMILTON

AT 3:24 P.M., MAY 7, 1945, THE PHONE RANG IN THE LONDON bureau of the Associated Press. The newsroom, as later described, was filled with cigarette smoke and anticipation. Hitler and Mussolini were dead. The Russians were in Berlin. German forces had surrendered in Baldham, Breslau, the Netherlands, and elsewhere. Allied forces occupied Flensburg, on the Danish border, where the caretaker Reich Government was now located. Allied heads of state were writing victory speeches, their staffs planning celebrations. But when would the war officially end?

Now, with the ringing phone, the answer came. This is Paris calling, said a faint voice over a military line. Lewis Hawkins could not recognize the callers voice. He asked for verification. Edward Kennedy, the head of the Paris bureau, got on the phone.

This is Ed Kennedy, Lew. Germany has surrendered unconditionally. Thats surrendered unconditionally. Thats official. Make the date Reims, France, and get it out.

The London staff took dictation until the connection, which faded in and out, went dead in the middle of a quote from German general Alfred Jodl, chief of operations staff in the German High Command, who had signed the surrender document at Reims. Kennedy had sent about three hundred words.

Well, said Kennedy to his staff after hanging up the phone, now lets see what happens.

Within minutes, the AP had the story out on the wires. Radio stations across the United States interrupted programming to announce the news. Newspapers flooded the streets with extra editions. Kennedys byline appeared under a highly unusual four-line headline spread across the front page of the New York Times.

This should have been a moment of triumph for the AP war reporter. But it was not, as explained by a press report the next day:

Edward Kennedy, chief of The Associated Press Western Front staff, who scored the news beatacclaimed by editors throughout the United States as one of the greatest in newspaper historywas indefinitely suspended from all further dispatching facilities by Supreme Headquarters in Paris.

What had Kennedy done wrong? He and sixteen other reporters had been allowed to witness the middle-of-the-night German surrender to General Dwight D. Eisenhower at his Reims headquarters on the condition of holding the story until given the green light. Then, on the afternoon of May 7, when the correspondents were back in Paris, a German radio broadcast from Flensburg announced the unconditional capitulation of all fighting troops. Kennedy, who suspected Allied forces had authorized the broadcast, considered the embargo voided and told a senior Army censor he no longer felt obliged to uphold the agreement. Using a military phone connection to London that was not subject to censorship, Kennedy broke the story. British censors, having no brief for handling surrender stories and, in any case, dealing with a story from abroad where other censors had responsibility, raised no objections.

The lifting of Kennedys credentials was only the beginning of his troubles. Furious and embarrassed at being beaten, fellow correspondents the next day gathered at the Hotel Scribe, where Allied press operations were centralized, and voted 542 to condemn him for the most disgraceful, deliberate and unethical double-cross in the history of journalism. At first put on indefinite suspension by Cooper, then quietly let go, his promising career with the Associated Press was over. Kennedy was forty years old.

The owner of the Santa Barbara News-Press in California, who thought Kennedy was in the right, hired him as the papers managing editor. Kennedy was struck by an automobile in 1963 and died five days later, age fifty-eight. This memoir of his career in the Associated Press foreign service has never been published.

* * *

By the end of World War II, Edward Kennedy had become one of the APs most respected reporters in the field. His experience was so deep and varied that very few peoplejournalist, diplomat, soldiercould match him. Even with the massive improvements in communication and travel that have come since, he stands out.

Kennedy embraced international adventure at a young age. He headed to Paris in 1927 as a student, enjoying the heady atmosphere and staying until his wallet was empty. He returned four years later, living on meager wages working for the Chicago Tribunes Paris newspaper, which along with the Paris Herald was an incubator of many of the centurys greatest correspondents. Once back in the United States, he hitched up to the Associated Press, which became an express ticket back to Europe. After stints in AP bureaus in Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C., and an obligatory stop at the New York foreign desk, he arrived in Paris in September 1935 at the moment the League of Nations fumbled its and the worlds future in failing to stand up to Fascist aggression.

Kennedy built his AP career country by country, battle by battle. He observed Fascists in Spain and Italy. He covered the ugliness of French colonial rule in northern Africa and Syria. He was posted in Cairo, then subject to English rule, and he was sent throughout Eastern Europe and the Balkans, torn seemingly forever by ethnic blood feuds. He observed inefficient and shaky regimes in these placesrulers who were not up to the jobs and who wouldnt hold them for long.