Copyright 2004 by Cathy Day

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be

mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

www.HarcourtBooks.com

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, organizations, and events

are the products of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any

resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely

coincidental.

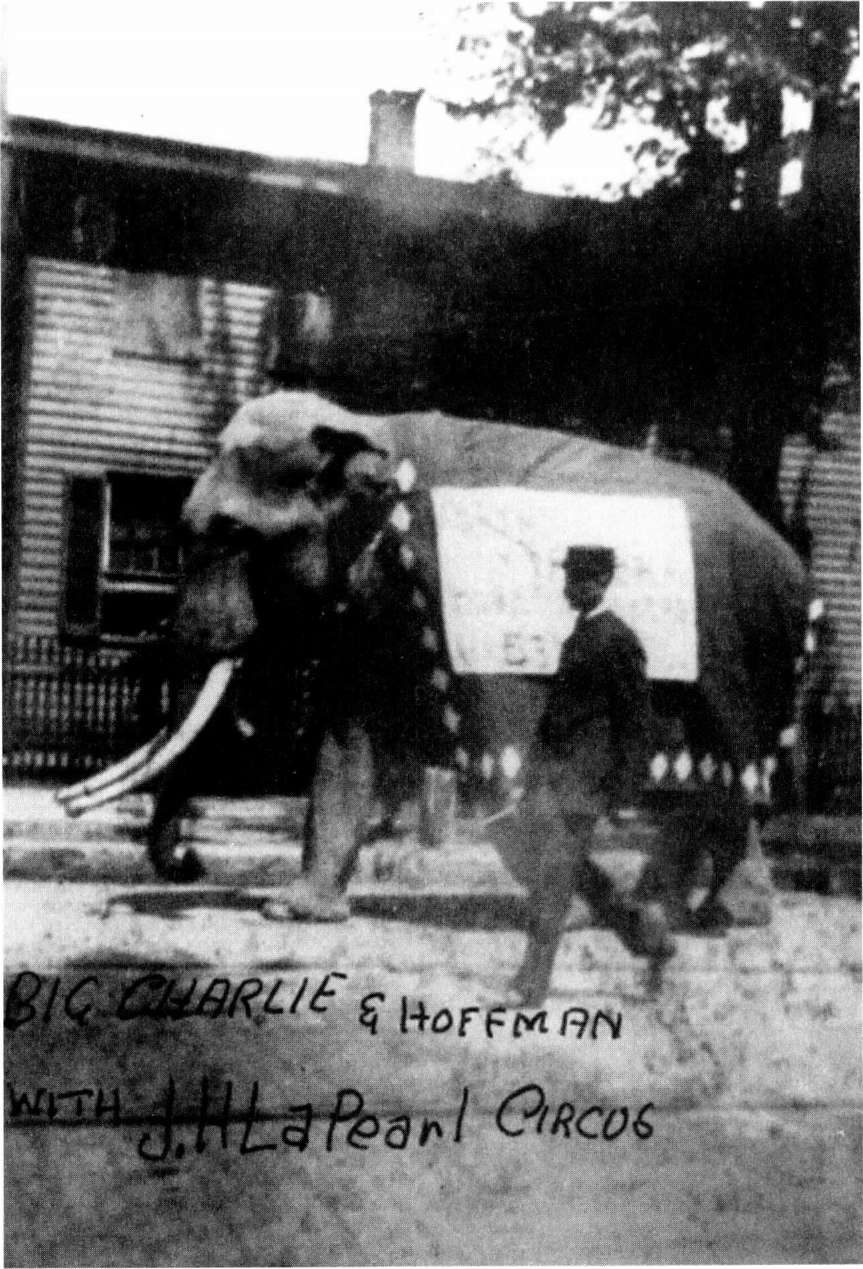

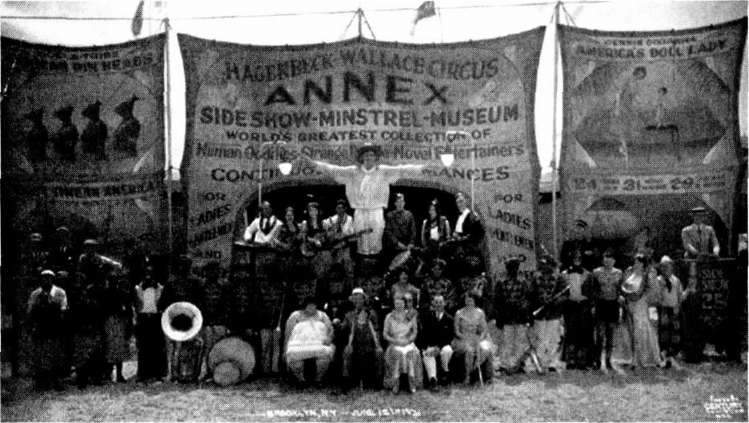

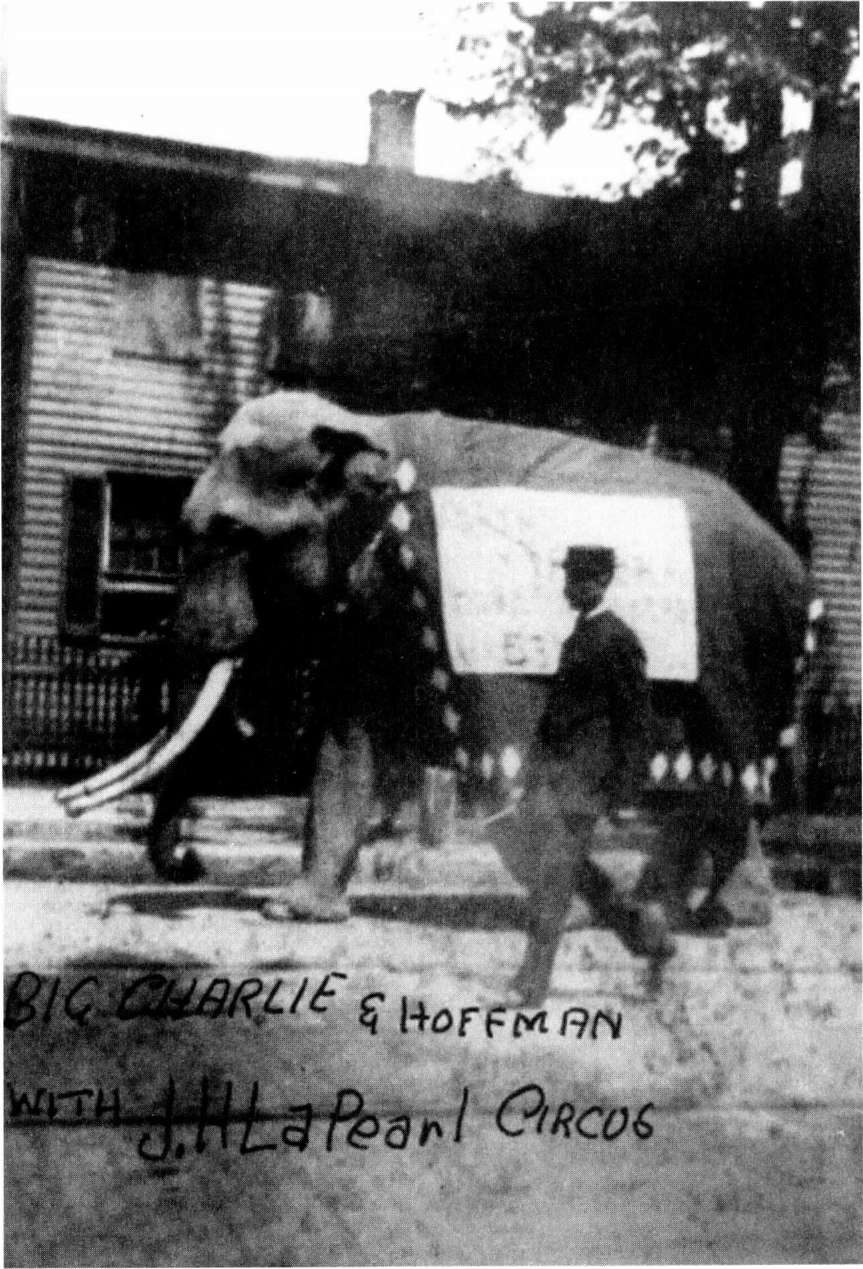

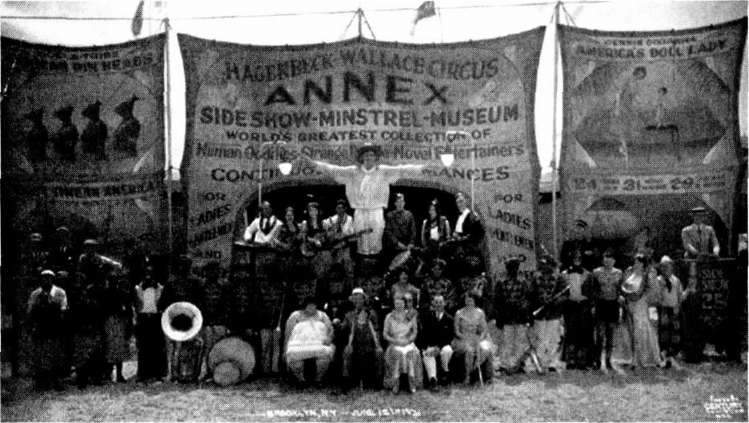

Photo credits: Pages ii, , and endpapers courtesy of

the Miami County Historical Society; , photograph by Edward J. Kelty

courtesy of the George Eastman House; from the H.A. Atwell Studio,

Chicago, Lillian Leitzel. black-and-white photograph, collection of the John

and Mable Ringling Museum of Art and the State Art Museum of Florida;

from the collection of Robert

C. Cole; , photograph by Tony Hare.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Day, Cathy.

The circus in winter/Cathy Day.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. CircusFiction. 2. Circus performersFiction. 3. IndianaFiction.

I. Title.

PS3604.A985C57 2004

813'.6dc22 2003025033

ISBN 0-15-101048-X

ISBN-13: 978-0156-03202-5 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 0-15-603202-3 (pbk.)

Text set in Meridien

Designed by Linda Lockowitz

Printed in the United States of America

First Harvest edition 2005

K J I H G F E D C B A

For the five of us

Weather: In the Midwest, around the lower Lakes, the sky in the winter is heavy and close, and it is a rare day, a day to remark on, when the sky lifts and allows the heart up.

WILLIAM GASS ,

"In the Heart of the Heart of the Country"

WALLAGE PORTER

or

What It Means

to See the Elephant

CIRCUS PROPRIETORS are not born to sawdust and spangles. Consider this: P. T. Barnum was nothing more than a dry-goods peddlerthat is until he bought a black woman for $1,000, a sum he quickly recouped by displaying her as George Washington's 161-year-old mammy. Barnum's business partner, James Bailey, was born little Jimmy McGinnisan orphaned bellboy transformed into circus mastermind, a man who taught army quartermasters the science of transporting masses of men and equipment by rail. Before trains, circuses traveled by horse-drawn wagons (and were called "mud shows" for obvious reasons) and by riverboat. If it hadn't been for paddle wheels and tall stacks, brothers Al, Alf, Charles, John, and Otto Rungeling might have become Iowa harness makers, like their father. But one morning along the Mississippi in 1870, the brothers were smitten with an elephant lumbering down a circus steamboat gangplank and became forever after the Ringling Brothers, owners (along with Barnum and Bailey) of the Greatest Show on Earth.

For many years, their greatest rival was the Great Porter Circus, owned by one Wallace Porter, a former Union cavairy officer. After Appomattox, Porter took his hard-won equine knowledge, applied it to the family's business, and became, at the age of thirty-eight, the owner of the largest livery stable in northern Indiana. How he became a circus man is another story altogether.

EACH SUMMER , Wallace Porter boarded a train in Lima, Indiana, and headed due east through Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey to the strange land of a million people, New York City. He employed a number of lawyers and bankers to oversee the profits from his stables and dutifully met with them once a year to discuss markets and dividends. These obligations dispensed with, he hailed a carriage and disappeared into the swarm of the city, following the true impetus of his trip. Wallace Porter went to New York to indulge in extravagance.

During his weeklong stay, he hardly slept, so intent was he to glut himself on the city. In the mornings, he had a shave and walked along the avenues down the length of Manhattan, which, in the late 1800s, was not an arduous undertaking. He handled his business over lunch, and afterward, he visited the finest men's tailors in the city and bought new shirts, Chesterfield coats, leather boots, and bowler hatsall of which were shipped back to Lima in enormous Saratoga trunks. At night, he dined out in the best restaurants, gorging himself on pheasant and artichokes. He drowned in vintage French wines. After dinner, he took in a play or the symphony, and then, until the small hours of the night, he roamed the parks alone. In Lima, such lavishness was a mark of poor character, a flaw almost impossible to hide, which was why Porter enjoyed the brief anonymity of the city. On the train ride back home, Porter tallied his expenses and hid that figure in his breast pocket like a guilty boy. He felt his thrifty father's eyes upon him, heard his voice saying, So what you can afford this? The money would buy more horses, carriages, a month's worth of hay. To punish himself, Porter lived a spartan existence the rest of the year, but come summer, he had to board the train, like a fish that must spawn. Always, he returned to Indiana feeling both completely hollow and fully sated.

The trip he took to New York in 1883 was different than the others, because that was the year he met Irene, who would become his wife. His banker, Irene's father, invited him to a Fourth of July party and introduced Porter to his guests as "my new friend, the pioneer from Indiana." Porter looked nothing like a settler, but something about the name itself, Lima, invoked the exotic and the adventurous.

The party was given on a warm summer evening. Irene's father decked the house in red, white, and blue, and instructed the small band he'd hired to play Sousa marches every so often to get folks in the patriotic mood. Irene descended the stairs to "Bonnie Annie Laurie" and caught Porter's eye as he stood near the punch bowl smoking a cigar. He was handsome in a smallish way that with his clothes and carriage passed for a kind of elegance. When he saw Irene, he dashed his cigar out in a cup of punch and met her at the bottom of the stairs. He took her hand, she smiled, and he realized then that since the war, he'd felt little within his heart except ambition, hardly an emotion at all.

Together, they watched the fireworks display as they ambled in the garden. "Tell me about this town of yours. Lima." Lee-ma, she said.

With a smile, Porter said, "Actually, it's like the bean."

"Are they grown there?"

"It's supposed to be Lee-ma, but I don't think the town fathers knew that." Porter recited a list of mispronounced Midwestern towns named for faraway places: Ver-sails, Brazz-ill, Kay-roh, New Praygue.

Irene laughed. "Tell me about Lie-ma."

So he described the countryside: He lived outside town along the Winnesaw, the river that separated the northern and southern halves of Lima. He described his monthly travel circuit to check on his stables, and again, gave her a litany of town names: Kokomo, Lafayette, Monticello, Rensselaer, Valparaiso, Nappanee, Warsaw, Alexandria. Irene repeated them, like someone trying to learn a foreign language. Bursts of fireworks lit Irene's face, and Porter said, "You should travel west sometime and see a bit of the world."

Next page